Back Veda ALS वेद ANP فيدا Arabic বেদ Assamese Vedes AST Vedalar Azerbaijani Wéda BAN Vėdas BAT-SMG Veda BCL Веды (індуізм) Byelorussian

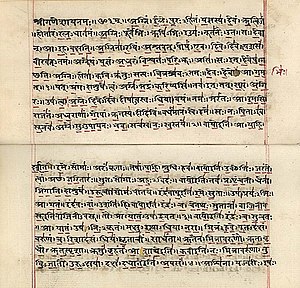

Die Vedas (Sanskrit: वेद veda, "kennis") is ’n groot hoeveelheid geskrifte met hul oorsprong op die Indiese subkontinent. Die manuskripte, in Sanskrit, is die oudste geskrifte van Hindoeïsme.[1][2] Hindoes beskou die Vedas as apauruṣeya ("nie van ’n mens nie, bomenslik"[3] en "onpersoonlik, anoniem").[4][5][6]

Vedas word ook genoem śruti ("wat gehoor word") letterkunde,[7] wat dit onderskei van smṛti ("wat onthou word") godsdienstekste. Die Vedas word deur ortodokse Indiese teoloë beskou as onthullings wat deur antieke wysgeers gesien is ná intense meditasie, en teks wat sedert antieke tye versigtig bewaar word.[8][9] In die epiese Hindoegedig Mahabharata kry die god Brahma die lof vir die skepping van die Vedas.[10] Volgens die Vediese himnes self is hulle vernuftig deur rishi's (wysgeers) geskep ná geïnspireerde skeppingsvernuf, nes ’n timmerman ’n strydwa bou.[9]

Daar is vier Vedas: die Rigveda, Yajurveda, Samaveda en Atharvaveda.[11][12] Elk word onderverdeel in vier groot tekstipes – die Samhitas (mantras en seëngebede), Aranyakas (geskrifte oor rituele, seremonies en offerandes), Brahmanas (kommentaar op rituele, seremonies en offerandes) en Upanishads (teks wat meditasie, filosofie en spirituele kennis bespreek).[11][13] Sommige geleerdes voeg ’n vyfde kategorie by: die Upasanas (aanbidding).[14][15]

Die verskillende Indiese filosofieë en denominasies het verskillende sienings van die Vedas. Skole wat die geskrifte as hul skriftelike gesag beskou, word "ortodoks" (āstika) genoem.[16] Ander tradisies, soos die Lokayata, Carvaka, Ajivika, Boeddhisme en Djainisme, vir wie die Vedas nie gesaghebbend is nie, word "heterodoks" of "nie-ortodoks" (nāstika) genoem.[17][18] Ondanks hul verskille, bespreek die verskillende Vedas dieselfde idees en begrippe.[17]

- ↑ Radhakrishnan & Moore 1957, p. 3

- ↑ Sanujit Ghose (2011). "Religious Developments in Ancient India" in Ancient History Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Vaman Shivaram Apte, The Practical Sanskrit-English Dictionary

- ↑ D Sharma, Classical Indian Philosophy: A Reader, Columbia University Press, ISBN , ble. 196-197

- ↑ Jan Westerhoff (2009), Nagarjuna's Madhyamaka: A Philosophical Introduction, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-538496-3, ble. 290

- ↑ Warren Lee Todd (2013), The Ethics of Śaṅkara and Śāntideva: A Selfless Response to an Illusory World, ISBN 978-1-4094-6681-9, ble. 128

- ↑ Apte 1965, p. 887

- ↑ Sheldon Pollock (2011), Boundaries, Dynamics and Construction of Traditions in South Asia (red.: Federico Squarcini), Anthem, ISBN 978-0-85728-430-3, ble. 41-58

- ↑ 9,0 9,1 Hartmut Scharfe (2002), Handbook of Oriental Studies, BRILL Academic, ISBN 978-9004125568, ble. 13-14

- ↑ Seer of the Fifth Veda: Kr̥ṣṇa Dvaipāyana Vyāsa in the Mahābhārata Bruce M. Sullivan, Motilal Banarsidass, ble. 85-86

- ↑ 11,0 11,1 Gavin Flood (1996), An Introduction to Hinduism, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-43878-0, ble. 35-39

- ↑ Bloomfield, M. The Atharvaveda and the Gopatha-Brahmana, (Grundriss der Indo-Arischen Philologie und Altertumskunde II.1.b.) Strassburg 1899; Gonda, J. A history of Indian literature: I.1 Vedic literature (Samhitas and Brahmanas); I.2 The Ritual Sutras. Wiesbaden 1975, 1977

- ↑ Jan Gonda (1975), Vedic Literature: (Saṃhitās and Brāhmaṇas), Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3-447-01603-2

- ↑ A Bhattacharya (2006), Hindu Dharma: Introduction to Scriptures and Theology, ISBN 978-0-595-38455-6, ble. 8-14

- ↑ Barbara A. Holdrege (1995), Veda and Torah: Transcending the Textuality of Scripture, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-1640-2, ble. 351-357

- ↑ Elisa Freschi (2012), Duty, Language and Exegesis in Prabhakara Mimamsa, BRILL, ISBN 978-9004222601, bl. 62

- ↑ 17,0 17,1 Flood 1996, p. 82

- ↑ "astika" en "nastika". Encyclopædia Britannica Online, 20 April 2016