Back عبد القدير خان Arabic عبد القادر خان ARZ عبدالقدیر خان AZB Абдул Кадир Хан Bulgarian আবদুল কাদের খান Bengali/Bangla Abdul Qadeer Khan Catalan Abdul Kádir Chán Czech Abdul Qadeer Khan Danish Abdul Kadir Khan German Abdul Qadir Khan Spanish

Abdul Qadeer Khan | |

|---|---|

ڈاکٹر عبدالقدیر خان | |

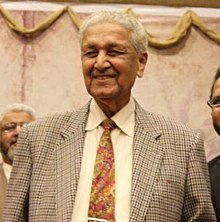

Khan in 2017 | |

| Born | 1 April 1936 |

| Died | 10 October 2021 (aged 85) Islamabad, Pakistan |

| Nationality | Pakistani |

| Alma mater | University of Karachi Delft University of Technology Catholic University of Louvain D. J. Sindh Government Science College[2] |

| Known for | Pakistan's nuclear weapons program, gaseous diffusion, martensite and graphene morphology |

| Spouse |

Hendrina Reternik (m. 1963) |

| Children | 2 |

| Awards | |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Metallurgical engineering |

| Institutions | Khan Research Laboratories GIK Institute of Technology Hamdard University Urenco Group |

| Thesis | The effect of morphology on the strength of copper-based martensites (1972) |

| Doctoral advisor | Martin J. Brabers[1] |

| Science Advisor to the Presidential Secretariat | |

| In office 1 January 2001 – 31 January 2004 | |

| President | Pervez Musharraf |

| Preceded by | Ishfaq Ahmad |

| Succeeded by | Atta-ur-Rahman |

| Personal details | |

| Political party | Tehreek-e-Tahaffuz-e-Pakistan (2012–2013) |

| Website | draqkhan.com.pk (archived) |

Abdul Qadeer Khan, NI, HI, FPAS (/ˈɑːbdəl ˈkɑːdɪər ˈkɑːn/ AHB-dəl KAH-deer KAHN; Urdu: عبد القدیر خان; 1 April 1936 – 10 October 2021),[3] known as A. Q. Khan, was a Pakistani nuclear physicist and metallurgical engineer who is colloquially known as the "father of Pakistan's atomic weapons program".[a]

An émigré (Muhajir) from India who migrated to Pakistan in 1952, Khan was educated in the metallurgical engineering departments of Western European technical universities where he pioneered studies in phase transitions of metallic alloys, uranium metallurgy, and isotope separation based on gas centrifuges. After learning of India's "Smiling Buddha" nuclear test in 1974, Khan joined his nation's clandestine efforts to develop atomic weapons when he founded the Khan Research Laboratories (KRL) in 1976 and was both its chief scientist and director for many years.

In January 2004, Khan was subjected to a debriefing by the Musharraf administration over evidence of nuclear proliferation handed to them by the Bush administration of the United States.[6][7] Khan admitted his role in running a nuclear proliferation network – only to retract his statements in later years when he leveled accusations at the former administration of Pakistan's Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto in 1990, and also directed allegations at President Musharraf over the controversy in 2008.[8][9][10]

Khan was accused of selling nuclear secrets illegally and was put under house arrest in 2004. After years of house arrest, Khan successfully filed a lawsuit against the Federal Government of Pakistan at the Islamabad High Court whose verdict declared his debriefing unconstitutional and freed him on 6 February 2009.[11][12] The United States reacted negatively to the verdict and the Obama administration issued an official statement warning that Khan still remained a "serious proliferation risk".[13]

On account of the knowledge of nuclear espionage by Khan and his contribution to nuclear proliferation throughout the world post 1970s, and the renewed fear of weapons of mass destruction in the hands of terrorists after the September 11 attacks, former CIA Director George Tenet described Khan as "at least as dangerous as Osama bin Laden".[14][15]

After his death on 10 October 2021, he was given a state funeral at Faisal Mosque before being buried at the H-8 graveyard in Islamabad.

- ^ "The Wrath of Khan". The Atlantic. 4 February 2004. Archived from the original on 14 May 2008. Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

arynewswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Abdul Qadeer Khan at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ (IISS), International Institute for Strategic Studies (1 May 2007). "Bhutto was father of Pakistan's Atom Bomb Programme". International Institute for Strategic Studies. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

PakObserverwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "A.Q. Khan & Iran". Global Security. Archived from the original on 24 October 2014. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ^ Staff (16 April 2006). "Chronology: A.Q. Khan". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 March 2015. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ^ "Mush helped proliferate N-technology : AQ Khan". The Times of India. 6 July 2008. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013.

- ^ "AQ Khan". Global Security.

- ^ Rashid, Ahmed (2012). Pakistan in the Brink. Allen Lane. pp. 60–61. ISBN 9781846145858.

- ^ "IHC declares Dr A Q Khan a free citizen". GEO.tv. 6 February 2009. Archived from the original on 15 April 2012. Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- ^ Rashid, Ahmed (2012). Pakistan in the Brink. Allen Lane. pp. 63–64. ISBN 9781846145858.

- ^ Warrick, Joby Warrick (7 February 2009). "Nuclear Scientist A.Q. Khan Is Freed From House Arrest". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- ^ "AQ Khan: The most dangerous man in the world?". 10 October 2021. Retrieved 11 October 2024.

- ^ "ڈاکٹر عبدالقدیر خان: کیا پاکستان کے جوہری سائنسدان دنیا کے سب سے خطرناک آدمی تھے؟". BBC News اردو (in Urdu). Retrieved 11 October 2024.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).