Back Eneïde Afrikaans Eneida AN Æneid ANG الإنيادة Arabic انياده ARZ Eneida AST Eneida Azerbaijani Энеида Bashkir Энеіда Byelorussian Энэіда BE-X-OLD

| Aeneid | |

|---|---|

| by Virgil | |

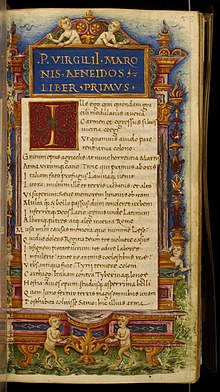

Manuscript circa 1470, Cristoforo Majorana | |

| Original title | AENEIS |

| Translator | John Dryden Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey Seamus Heaney Allen Mandelbaum Robert Fitzgerald Robert Fagles Frederick Ahl Sarah Ruden |

| Written | 29–19 BC |

| First published in | 19 BC |

| Country | Roman Republic |

| Language | Classical Latin |

| Subject(s) | Epic Cycle, Trojan War, Founding of Rome |

| Genre(s) | Epic poem |

| Meter | Dactylic hexameter |

| Publication date | 1469 |

| Published in English | 1697 |

| Media type | Manuscript |

| Lines | 9,896 |

| Preceded by | Georgics |

| Full text | |

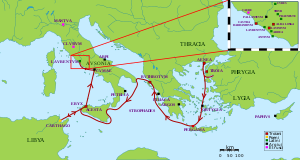

The Aeneid (/ɪˈniːɪd/ ih-NEE-id; Latin: Aenēĭs [ae̯ˈneːɪs] or [ˈae̯neɪs]) is a Latin epic poem that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Trojan who fled the fall of Troy and travelled to Italy, where he became the ancestor of the Romans. Written by the Roman poet Virgil between 29 and 19 BC, the Aeneid comprises 9,896 lines in dactylic hexameter.[1] The first six of the poem's twelve books tell the story of Aeneas' wanderings from Troy to Italy, and the poem's second half tells of the Trojans' ultimately victorious war upon the Latins, under whose name Aeneas and his Trojan followers are destined to be subsumed.

The hero Aeneas was already known to Greco-Roman legend and myth, having been a character in the Iliad. Virgil took the disconnected tales of Aeneas' wanderings, his vague association with the foundation of Rome and his description as a personage of no fixed characteristics other than a scrupulous pietas, and fashioned the Aeneid into a compelling founding myth or national epic that tied Rome to the legends of Troy, explained the Punic Wars, glorified traditional Roman virtues, and legitimised the Julio-Claudian dynasty as descendants of the founders, heroes, and gods of Rome and Troy.

The Aeneid is widely regarded as Virgil's masterpiece and one of the greatest works of Latin literature.[2][3][4]

- ^ Gaskell, Philip (1999). Landmarks in Classical Literature. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn. p. 161. ISBN 1-57958-192-7.

- ^ Aloy, Daniel (22 May 2008). "New translation of 'Aeneid' restores Virgil's wordplay and original meter". Cornell Chronicle. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ^ Damen, Mark (2004). "Chapter 11: Vergil and The Aeneid". Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ^ Gill, N. S. "Why Read the Aeneid in Latin?". About.com. Archived from the original on 24 October 2016. Retrieved 5 December 2016.