Back Afro-Américains dans la guerre d’indépendance des États-Unis French په انقلابي جګړه کې افريقايي الاصله امريکايان Pashto/Pushto Афроамериканцы в войне за независимость США Russian

| Part of a series on |

| African Americans |

|---|

African Americans fought on both sides the American Revolution, the Patriot cause for independence as well as in the British army, in order to achieve their freedom from enslavement.[1] It is estimated that 20,000 African Americans joined the British cause, which promised freedom to enslaved people, as Black Loyalists. About half that number, an estimated 9,000 African Americans, became Black Patriots.[2]

Between 220,000 and 250,000 soldiers and militia served the American cause in total, suggesting that Black soldiers made up approximately four percent of the Patriots' numbers. Of the 9,000 Black soldiers, 5,000 were combat-dedicated troops.[3] The average length of time in service for an African American soldier during the war was four and a half years (due to many serving for the whole eight-year duration), which was eight times longer than the average period for white soldiers. Meaning that while they were only four percent of the manpower base, they comprised around a quarter of the Patriots' strength in terms of man-hours, though this includes supportive roles.[4]

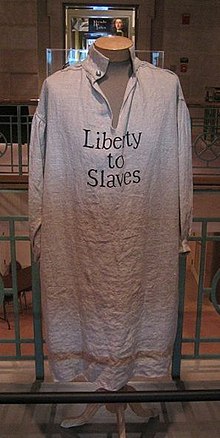

About 20,000 people escaped slavery, joined, and fought for the British army.[5] Much of this number was seen after Dunmore's Proclamation, and subsequently the Philipsburg Proclamation issued by Sir Henry Clinton.[6] Though between only 800–2,000 people who were enslaved reached Dunmore himself, the publication of both proclamations provided incentive for nearly 100,000 enslaved people across the American Colonies to escape, lured by the promise of freedom.[7]

In March 1770, Black Bostonian Crispus Attucks was part of the large crowd taunting British soldiers and was one of the number they shot in the incident Patriots called the Boston Massacre.[8] He is considered an iconic martyr of Patriots.[9]

- ^ Gilbert, Alan. Black Patriots and Loyalists: Fighting for Emancipation in the War for Independence. Chicago: University of Chicago Press 2012

- ^ Nash, "The African Americans' Revolution," at p 254

- ^ Lanning, Michael Lee. "African Americans in the Revolutionary War." p. 177.

- ^ Michael Lee Lanning. "African Americans in the Revolutionary War." Page 178.

- ^ "The Ex-Slaves Who Fought with the British". 28 September 2021.

- ^ Carnahan, Burrus M. (2007). Act of Justice: Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation and the Law of War. University Press of Kentucky. p. 18. ISBN 0-8131-2463-8

- ^ Bristow, Peggy (1994). We're Rooted Here and They Can't Pull Us Up: Essays in African Canadian Women's History. University of Toronto Press. p. 19. ISBN 0-8020-6881-2.

- ^ "John Adams and the Boston Massacre Trials".

- ^ "Crispus Attucks". Biography. Retrieved 2018-06-20.