Back تقلید پرخاشگر Persian חקיינות אגרסיבית HE Mimikri agresif ID ペッカム型擬態 Japanese აგრესიული მიმიკრია Georgian یرغلیز تقلید Pashto/Pushto 攻擊型擬態 ZH-YUE

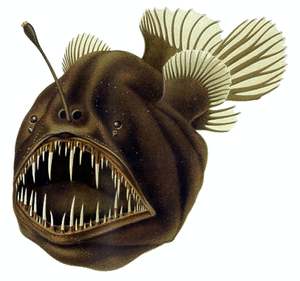

Aggressive mimicry is a form of mimicry in which predators, parasites, or parasitoids share similar signals, using a harmless model, allowing them to avoid being correctly identified by their prey or host. Zoologists have repeatedly compared this strategy to a wolf in sheep's clothing.[2][3][4] In its broadest sense, aggressive mimicry could include various types of exploitation, as when an orchid exploits a male insect by mimicking a sexually receptive female (see pseudocopulation),[5] but will here be restricted to forms of exploitation involving feeding. For example, indigenous Australians who dress up as and imitate kangaroos when hunting would not be considered aggressive mimics, nor would a human angler, though they are undoubtedly practising self-decoration camouflage. Treated separately is molecular mimicry, which shares some similarity; for instance a virus may mimic the molecular properties of its host, allowing it access to its cells. An alternative term, Peckhamian mimicry, has been suggested (after George and Elizabeth Peckham),[6][7][8] but it is seldom used.[a]

Aggressive mimicry is opposite in principle to defensive mimicry, where the mimic generally benefits from being treated as harmful. The mimic may resemble its own prey, or some other organism which is beneficial or at least not harmful to the prey. The model, i.e. the organism being 'imitated', may experience increased or reduced fitness, or may not be affected at all by the relationship. On the other hand, the signal receiver inevitably suffers from being tricked, as is the case in most mimicry complexes.

Aggressive mimicry often involves the predator employing signals which draw its potential prey towards it, a strategy which allows predators to simply sit and wait for prey to come to them. The promise of food or sex are most commonly used as lures. However, this need not be the case; as long as the predator's true identity is concealed, it may be able to approach prey more easily than would otherwise be the case. In terms of species involved, systems may be composed of two or three species; in two-species systems the signal receiver, or "dupe", is the model.

In terms of the visual dimension, the distinction between aggressive mimicry and camouflage is not always clear. Authors such as Wickler[8] have emphasized the significance of the signal to its receiver as delineating mimicry from camouflage. However, it is not easy to assess how 'significant' a signal may be for the dupe, and the distinction between the two can thus be rather fuzzy. Mixed signals may be employed: aggressive mimics often have a specific part of the body sending a deceptive signal, with the rest being hidden or camouflaged.

- ^ Haddock, Steven H.D.; Moline, Mark A.; Case, James F. (2010). "Bioluminescence in the Sea". Annual Review of Marine Science. 2: 443–493. Bibcode:2010ARMS....2..443H. doi:10.1146/annurev-marine-120308-081028. PMID 21141672. S2CID 3872860.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

NelsonJackson2009was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

HenebergPerger2018was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Levine2014was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Wickler, Wolfgang (1965). "Mimicry and the evolution of animal communication". Nature. 208 (5010): 519–21. Bibcode:1965Natur.208..519W. doi:10.1038/208519a0. S2CID 37649827.

- ^ Peckham, Elizabeth G. (1889). "Protective resemblances of spiders" (PDF). Occasional Papers of Natural History Society of Wisconsin. 1: 61–113.

- ^ Peckham, Elizabeth G.; Peckham, George W. (1892). "Ant-like spiders of the family Attidae" (PDF). Occasional Papers of Natural History Society of Wisconsin. 2: 1–84.

- ^ a b Wickler, Wolfgang (1968). Mimicry in plants and animals. McGraw-Hill.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).