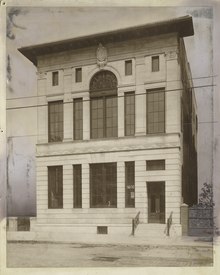

Harlem's Little Library Theatre in the 135th Street branch of the New York Public Library hosted ANT's early performances. | |

| Formation | 1940 |

|---|---|

| Dissolved | 1951 |

| Type | Theatre group |

| Purpose | A people's theatre for Black drama |

| Location |

|

Membership | Sidney Poitier, Harry Belafonte, Ruby Dee and Ossie Davis |

Artistic director(s) | Abram Hill, Frederick O'Neal and John O’Shaughnessy |

The American Negro Theatre (ANT) was co-founded on June 5, 1940 by playwright Abram Hill and actor Frederick O'Neal.[1] Determined to build a "people's theatre", they were inspired by the Federal Theatre Project's Negro Unit in Harlem and by W. E. B. Du Bois' "four fundamental principles" of Black drama: that it should be by, about, for, and near African Americans.[2][3][4]

The ANT produced 12 original Black plays and seven adaptations of non-Black work for tens of thousands of primarily Black audiences in its first nine years.[4][5] The Black playwrights whose work the company produced included Countee Cullen (One Way To Heaven), Theodore Browne (Go Down Moses and Natural Man), Owen Dodson (Garden of Time), Alvin Hill (Walk Hard) and Curtis Cooksey (Starlight).[5]

In addition to their theatre productions, the ANT also produced a weekly radio program in 1945, with a repertoire that spanned Shakespeare, Dickens and opera.[2] It also ran the Studio Theatre school of drama under the leadership of Osceola Archer, one of the first Black actresses on Broadway. Many of her students later had careers in the performing arts, including television comediennes Helen Martin (Good Times and 227), Emmy-winning Isabel Sanford (All in the Family and The Jeffersons), and Clarice Taylor (Sanford and Son and The Cosby Show);[1][6] stage and screen couple Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee,[7] movie actor Sidney Poitier, and singer-actor Harry Belafonte.[8] In a 1996 interview with Cornel West, Belafonte described how the American Negro Theatre opened his eyes to how "magical" theatre was. Belafonte said that he saw his first show in the ANT when he was given two tickets as a gratuity when working as a janitor's assistant for Clarice Taylor, who was in the play that night.[9]

Aside from teaching, Archer also directed plays for the ANT, most notably a 1948 command performance for First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt of an integrated production of Katherine Garrison Chapin's play Sojourner Truth, featuring Belafonte and actress Jill Miller.[10] Within the next few years, however, the ANT folded, a victim of repeated financial shortfalls and in-fighting over its mission in the wake of its Anna Lucasta success, for which its lead actress Alice Childress gained a Tony nomination for playing the title character.[11][12]

Theatre arts scholar Jonathan Shandell counts ANT's expansion of the "repertoire to include canonical black playwrights, use of a predominantly black cast and crew in all productions, and ... community outreach efforts, such as the free Uptown Shakespeare performances at Marcus Garvey Park" among its most important legacies.[1] The assessment of the curators of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture at New York Public Library, which hosted ANT's 75th Anniversary in 2016 explained the ANT's importance by pointing out that ANT "sought to push the boundaries of black theatre ... experimenting with modernist theatrical tropes, and producing ambitious, original works by Black playwrights. Ultimately, the American Negro Theatre became one of the most influential black theater organizations of the 1940s,"[13] while also cultivating a generation of professional Black actors, directors and other artists in the performing arts who continue to influence the culture today.

- ^ a b c "The American Negro Theatre and the Long Civil Rights Era". jadtjournal.org. Retrieved 2022-01-10.

- ^ a b Hill, Anthony Duane (2008-02-06). "American Negro Theatre (1940-ca. 1955) •". Retrieved 2022-01-09.

- ^ Hutchinson, George; Hutchinson, George Evelyn (2007-06-14). The Cambridge Companion to the Harlem Renaissance. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-67368-6.

- ^ a b "The American Negro Theater is Formed". African American Registry. Retrieved 2022-01-09.

- ^ a b "archives.nypl.org -- American Negro Theatre records". archives.nypl.org. Retrieved 2022-01-09.

- ^ "Alice Childress, the Last Woman Standing". The New Yorker. 2011-10-03. Retrieved 2022-01-10.

- ^ "Remembering Ruby Dee, Celebrating the American Negro Theatre". The New York Public Library. Retrieved 2022-01-16.

- ^ "Remembering Osceola Archer—Thespian, Activist". TAPinto. Retrieved 2022-01-12.

- ^ Frederick, Candice. "How the American Negro Theatre Shaped the Career of the Iconic Harry Belafonte". www.nypl.org. Archived from the original on 2015-07-09. Retrieved 2022-01-16.

- ^ "Remembering Osceola Archer: Summer Stock Director and Equity Advocate". www.putnamcountyny.com. Archived from the original on 2020-09-28. Retrieved 2022-01-12.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:4was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Marshall University et al. "American Negro Theater, 1930-1955." Clio: Your Guide to History. July 14, 2021. Accessed January 10, 2022. https://theclio.com/entry/1392

- ^ Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library. "The 75th Anniversary of the American Negro Theatre". www.nypl.org. Archived from the original on 2015-07-07. Retrieved 2022-01-16.