Back Andrew Johnson Afrikaans አንድሪው ጆንሰን Amharic Andrew Johnson AN Andreas Johnson ANG أندرو جونسون Arabic اندرو چونسون ARZ Andrew Johnson AST Endrü Conson Azerbaijani اندرو جانسون AZB Andrew Johnson BAN

Andrew Johnson | |

|---|---|

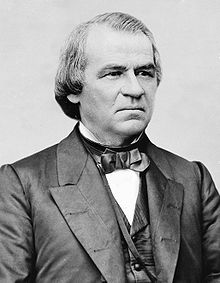

Portrait c. 1870–1875 | |

| 17th President of the United States | |

| In office April 15, 1865 – March 4, 1869 | |

| Vice President | None[a] |

| Preceded by | Abraham Lincoln |

| Succeeded by | Ulysses S. Grant |

| 16th Vice President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1865 – April 15, 1865 | |

| President | Abraham Lincoln |

| Preceded by | Hannibal Hamlin |

| Succeeded by | Schuyler Colfax |

| United States Senator from Tennessee | |

| In office March 4, 1875 – July 31, 1875 | |

| Preceded by | William G. Brownlow |

| Succeeded by | David M. Key |

| In office October 8, 1857 – March 4, 1862 | |

| Preceded by | James C. Jones |

| Succeeded by | David T. Patterson |

| Military Governor of Tennessee | |

| In office March 12, 1862 – March 4, 1865 | |

| Appointed by | Abraham Lincoln |

| Preceded by | Isham G. Harris (as Governor) |

| Succeeded by | William G. Brownlow (as Governor) |

| 15th Governor of Tennessee | |

| In office October 17, 1853 – November 3, 1857 | |

| Preceded by | William B. Campbell |

| Succeeded by | Isham G. Harris |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Tennessee's 1st district | |

| In office March 4, 1843 – March 3, 1853 | |

| Preceded by | Thomas Dickens Arnold |

| Succeeded by | Brookins Campbell |

| Personal details | |

| Born | December 29, 1808 Raleigh, North Carolina, U.S. |

| Died | July 31, 1875 (aged 66) Elizabethton, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Stroke |

| Resting place | Andrew Johnson National Cemetery, Greeneville, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic (from 1839)[1][2] |

| Other political affiliations | Independent (before 1839)[1][2] Mechanics' (Working Men's) (1829–1835)[3][4] National Union (1864–1868) |

| Spouse | |

| Children | |

| Parents |

|

| Profession |

|

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1862–1865 |

| Rank | Brigadier General (as Military Governor of Tennessee) |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Personal 16th Vice President of the United States 17th President of the United States Vice presidential and Presidential campaigns Post-presidency Family  |

||

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808 – July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, as he was vice president at that time. Johnson was a Democrat who ran with Abraham Lincoln on the National Union Party ticket, coming to office as the Civil War concluded. He favored quick restoration of the seceded states to the Union without protection for the newly freed people who were formerly enslaved as well as pardoning ex-Confederates. This led to conflict with the Republican-dominated Congress, culminating in his impeachment by the House of Representatives in 1868. He was acquitted in the Senate by one vote.

Johnson was born into poverty and never attended school. He was apprenticed as a tailor and worked in several frontier towns before settling in Greeneville, Tennessee, serving as an alderman and mayor before being elected to the Tennessee House of Representatives in 1835. After briefly serving in the Tennessee Senate, Johnson was elected to the House of Representatives in 1843, where he served five two-year terms. He became governor of Tennessee for four years, and was elected by the legislature to the Senate in 1857. During his congressional service, he sought passage of the Homestead Bill which was enacted soon after he left his Senate seat in 1862. Southern slave states seceded to form the Confederate States of America, including Tennessee, but Johnson remained firmly with the Union. He was the only sitting senator from a Confederate state who did not promptly resign his seat upon learning of his state's secession. In 1862, Lincoln appointed him as Military Governor of Tennessee after most of it had been retaken. In 1864, Johnson was a logical choice as running mate for Lincoln, who wished to send a message of national unity in his re-election campaign, and became vice president after a victorious election in 1864.

Johnson implemented his own form of Presidential Reconstruction, a series of proclamations directing the seceded states to hold conventions and elections to reform their civil governments. Southern states returned many of their old leaders and passed Black Codes to deprive the freedmen of many civil liberties, but Congressional Republicans refused to seat legislators from those states and advanced legislation to overrule the Southern actions. Johnson vetoed their bills, and Congressional Republicans overrode him, setting a pattern for the remainder of his presidency.[b] Johnson opposed the Fourteenth Amendment which gave citizenship to former slaves. In 1866, he went on an unprecedented national tour promoting his executive policies, seeking to break Republican opposition.[5] As the conflict grew between the branches of government, Congress passed the Tenure of Office Act restricting Johnson's ability to fire Cabinet officials. He persisted in trying to dismiss Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, but ended up being impeached by the House of Representatives and narrowly avoided conviction in the Senate. He did not win the 1868 Democratic presidential nomination and left office the following year.

Johnson returned to Tennessee after his presidency and gained some vindication when he was elected to the Senate in 1875, making him the only president to afterwards serve in the Senate. He died five months into his term. Johnson's strong opposition to federally guaranteed rights for black Americans is widely criticized. Historians have consistently ranked him one of the worst presidents in American history.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

- ^ a b Trefousse, pp. 38–42.

- ^ a b Gordon-Reed, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Trefousse, p. 35.

- ^ Gordon-Reed, pp. 33–36.

- ^ Castel 2002, p. 231.