Back Antigeen Afrikaans Antigen ALS مولد الضد Arabic প্ৰতিজন Assamese Antigen Azerbaijani Антыгены Byelorussian Антиген Bulgarian অ্যান্টিজেন Bengali/Bangla Antigen BS Antigen Catalan

In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule, moiety, foreign particulate matter, or an allergen, such as pollen, that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor.[1] The presence of antigens in the body may trigger an immune response.[2]

Antigens can be proteins, peptides (amino acid chains), polysaccharides (chains of simple sugars), lipids, or nucleic acids.[3][4] Antigens exist on normal cells, cancer cells, parasites, viruses, fungi, and bacteria.[1][3]

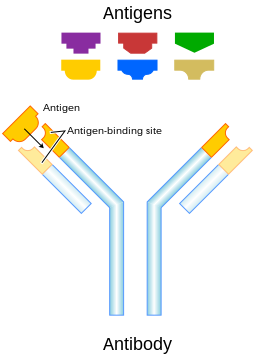

Antigens are recognized by antigen receptors, including antibodies and T-cell receptors.[3] Diverse antigen receptors are made by cells of the immune system so that each cell has a specificity for a single antigen.[3] Upon exposure to an antigen, only the lymphocytes that recognize that antigen are activated and expanded, a process known as clonal selection.[4] In most cases, antibodies are antigen-specific, meaning that an antibody can only react to and bind one specific antigen; in some instances, however, antibodies may cross-react to bind more than one antigen. The reaction between an antigen and an antibody is called the antigen-antibody reaction.

Antigen can originate either from within the body ("self-protein" or "self antigens") or from the external environment ("non-self").[2] The immune system identifies and attacks "non-self" external antigens. Antibodies usually do not react with self-antigens due to negative selection of T cells in the thymus and B cells in the bone marrow.[5] The diseases in which antibodies react with self antigens and damage the body's own cells are called autoimmune diseases.[6]

Vaccines are examples of antigens in an immunogenic form, which are intentionally administered to a recipient to induce the memory function of the adaptive immune system towards antigens of the pathogen invading that recipient. The vaccine for seasonal influenza is a common example.[7]

- ^ a b "Antibody". National Human Genome Research Institute, US National Institutes of Health. 2020. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ a b "Immune system and disorders". MedlinePlus, US National Institute of Medicine. 28 September 2020. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Antigen". Cleveland Clinic. 2023. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- ^ a b Abbas AK, Lichtman A, Pillai S (2018). "Antibodies and Antigens". Cellular and Molecular Immunology (9th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. ISBN 9780323523240. OCLC 1002110073.

- ^ Gallucci S, Lolkema M, Matzinger P (November 1999). "Natural adjuvants: endogenous activators of dendritic cells". Nature Medicine. 5 (11): 1249–1255. doi:10.1038/15200. PMID 10545990. S2CID 29090284.

- ^ Janeway Jr CA, Travers P, Walport M, Shlomchik MJ (2001). "Autoimmune responses are directed against self antigens". Immunobiology: The Immune System in Health and Disease (5th ed.). Elsevier España. ISBN 9780815336426. OCLC 45708106.

- ^ "Antigenic characterization". US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 15 October 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2020.