Back ديانة الأزتك Arabic Religión mexica Spanish دین آزتک Persian Religion aztèque French Agama Aztek ID Religione azteca Italian Ацтечка религија Macedonian Religião mexica Portuguese Religia aztecă Romanian Религија Астека Serbian

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Aztec civilization |

|---|

|

| Aztec society |

| Aztec history |

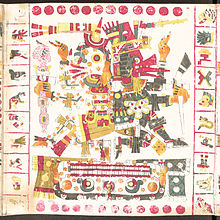

The Aztec religion is a polytheistic and monistic pantheism in which the Nahua concept of teotl was construed as the supreme god Ometeotl, as well as a diverse pantheon of lesser gods and manifestations of nature.[1] The popular religion tended to embrace the mythological and polytheistic aspects, and the Aztec Empire's state religion sponsored both the monism of the upper classes and the popular heterodoxies.[2]

The most important deities were worshiped by priests in Tenochtitlan, particularly Tlaloc and the god of the Mexica, Huitzilopochtli, whose shrines were located on Templo Mayor. Their priests would receive special dispensation from the empire. When other states were conquered the empire would often incorporate practices from its new territories into the mainstream religion.[3]

In common with many other indigenous Mesoamerican civilizations, the Aztecs put great ritual emphasis on calendrics, and scheduled festivals, government ceremonies, and even war around key transition dates in the Aztec calendar.[4] Public ritual practices could involve food, storytelling, and dance, as well as ceremonial warfare, the Mesoamerican ballgame, and human sacrifice.[5]

The cosmology of Aztec religion divides the world into thirteen heavens and nine earthly layers or netherworlds.[6] The first heaven overlaps with the first terrestrial layer, so that heaven and the terrestrial layers meet at the surface of the Earth. Each level is associated with a specific set of deities and astronomical objects. The most important celestial entities in Aztec religion are the Sun, the Moon, and the planet Venus (as both "morning star" and "evening star").[7]

After the Spanish Conquest, Aztec people were forced to convert to Catholicism. Aztec religion syncretized with Catholicism. This syncretism is evidenced by the Virgin of Guadalupe[8] and the Day of the Dead.

- ^ Maffie, James (2013). Aztec philosophy: understanding a world in motion. Boulder: University press of Colorado. ISBN 978-1-60732-222-1.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:2was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Berdan, Frances F., ed. (2014), "Religion, Science, and the Arts", Aztec Archaeology and Ethnohistory, Cambridge World Archaeology, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 234, doi:10.1017/cbo9781139017046.011, ISBN 978-0-521-88127-2, retrieved 2024-05-29

- ^ Hassig, Ross (2001). Time, history, and belief in Aztec and Colonial Mexico (1st ed.). Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-73139-4.

- ^ Smith, Michael Ernest (2011). The Aztecs. The peoples of America (3rd ed.). Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-9497-6.

- ^ Solís Olguín, Felipe R.; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, eds. (2004). The Aztec empire: published on the occasion of the exhibition The Aztec Empire; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, October 15, 2004 - February 13, 2005. New York, NY: Guggenheim Museum. ISBN 978-0-89207-321-4.

- ^ Milbrath, Susan (2019-06-25), "The Planets in Aztec Culture", Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Planetary Science, doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190647926.013.54, ISBN 978-0-19-064792-6, retrieved 2024-05-29

- ^ Beatty, Andrew (2006). "The Pope in Mexico: Syncretism in Public Ritual". American Anthropologist. 108 (2): 324–335. doi:10.1525/aa.2006.108.2.324. ISSN 0002-7294. JSTOR 3804794.