Back Biogeografie Afrikaans جغرافيا حيوية Arabic Biocoğrafiya Azerbaijani بیوجوغرافیا AZB Биогеография Bashkir Bioheograpiya BCL Біягеаграфія Byelorussian Біягеаграфія BE-X-OLD Биогеография Bulgarian जीवभूगोल Bihari

| Part of a series on |

| Evolutionary biology |

|---|

|

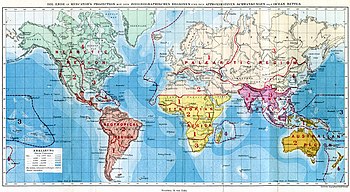

Biogeography is the study of the distribution of species and ecosystems in geographic space and through geological time. Organisms and biological communities often vary in a regular fashion along geographic gradients of latitude, elevation, isolation and habitat area.[1] Phytogeography is the branch of biogeography that studies the distribution of plants. Zoogeography is the branch that studies distribution of animals. Mycogeography is the branch that studies distribution of fungi, such as mushrooms.

Knowledge of spatial variation in the numbers and types of organisms is as vital to us today as it was to our early human ancestors, as we adapt to heterogeneous but geographically predictable environments. Biogeography is an integrative field of inquiry that unites concepts and information from ecology, evolutionary biology, taxonomy, geology, physical geography, palaeontology, and climatology.[2][3]

Modern biogeographic research combines information and ideas from many fields, from the physiological and ecological constraints on organismal dispersal to geological and climatological phenomena operating at global spatial scales and evolutionary time frames.

The short-term interactions within a habitat and species of organisms describe the ecological application of biogeography. Historical biogeography describes the long-term, evolutionary periods of time for broader classifications of organisms.[4] Early scientists, beginning with Carl Linnaeus, contributed to the development of biogeography as a science.

The scientific theory of biogeography grows out of the work of Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859),[5] Francisco Jose de Caldas (1768–1816),[6] Hewett Cottrell Watson (1804–1881),[7] Alphonse de Candolle (1806–1893),[8] Alfred Russel Wallace (1823–1913),[9] Philip Lutley Sclater (1829–1913) and other biologists and explorers.[10]

- ^ Brown University, "Biogeography." Accessed February 24, 2014. "Biogeography". Archived from the original on 2014-10-20. Retrieved 2014-04-08..

- ^ Dansereau, Pierre. 1957. Biogeography; an ecological perspective. New York: Ronald Press Co.

- ^ Cox, C. Barry; Moore, Peter D.; Ladle, Richard J. (2016). Biogeography:An Ecological and Evolutionary Approach. Chichester, UK: Wiley. p. xi. ISBN 9781118968581. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- ^ Cox, C Barry, and Peter Moore. Biogeography : an ecological and evolutionary approach. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publications, 2005.

- ^ von Humboldt 1805. Essai sur la geographie des plantes; accompagne d'un tableau physique des régions equinoxiales. Levrault, Paris.

- ^ Caldas F.J. 1796–1801. "La Nivelacion de las Plantas". Colombia.

- ^ Watson H.C. 1847–1859. Cybele Britannica: or British plants and their geographical relations. Longman, London.

- ^ de Candolle, Alphonse 1855. Géographie botanique raisonnée &c. Masson, Paris.

- ^ Wallace A.R. 1876. The geographical distribution of animals. Macmillan, London.

- ^ Browne, Janet (1983). The secular ark: studies in the history of biogeography. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-02460-9.