Back Amos Afrikaans Buch Amos ALS سفر عاموس Arabic ܣܦܪܐ ܕܥܡܘܣ ARC سفر عاموس ARZ Amos (Buach) BAR Buku Amos BBC Кніга прарока Амоса Byelorussian Кніга прарока Амоса BE-X-OLD Книга на пророк Амоса Bulgarian

| |||||

| Tanakh (Judaism) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Old Testament (Christianity) | |||||

|

|

|||||

| Bible portal | |||||

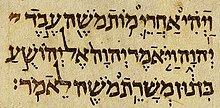

The Book of Amos is the third of the Twelve Minor Prophets in the Old Testament (Tanakh) and the second in the Greek Septuagint tradition.[1] According to the Bible, Amos was an older contemporary of Hosea and Isaiah,[2] and was active c. 750 BC during the reign of Jeroboam II[2] (788–747 BC) of Samaria (Northern Israel),[3] while Uzziah was King of Judah. Amos is said to have lived in the kingdom of Judah but preached in the northern Kingdom of Israel[2] with themes of social justice, God's omnipotence, and divine judgment became staples of prophecy.[2] In recent years, scholars have grown more skeptical of The Book of Amos’ presentation of Amos’ biography and background.[4] It is known for its distinct “sinister tone and violent portrayal of God.”[5]

- ^ Sweeney 2000, p. unpaginated.

- ^ a b c d Harris, Stephen L., Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985.

- ^ Finkelstein, Israel. The Forgotten Kingdom: The Archaeology and History of Ancient Israel. Atlanta: SBL, 2013. Ancient Near East Monographs, Number 5. p. 4.

- ^ Couey, J. Blake. The Oxford Handbook of the Minor Prophets. p. 424–436. 2021. “In more recent scholarship, one finds greater skepticism about historical reconstructions of Amos’s prophetic career. The superscription and Amaziah narrative are increasingly viewed as late, which raises questions about their historical validity (Coggins 2000 72, 142–143; Eidevall 2017, 3–7). The vision reports may also belong to later stages of the book’s development (Becker 2001; Eidevall 2017, 191–193). Doubts about the existence of a united monarchy under King David undermine arguments that Amos advocated for a reunified Davidic kingdom (Davies 2009, 60; Radine 2010, 4). These questions reflect larger scholarly trends, in which prophetic books are increasingly viewed as products of elite scribes. Even if they reflect historical prophetic activity, one cannot uncritically equate the prophet with the author. There may in fact have been no “writing prophets,” in which case Amos loses one source of his/its traditional prestige as the first of this group. Further complicating the matter, the portrait of prophets like Amos as proclaimers of judgment contrasts starkly with surviving records of prophetic activity from other ancient Near Eastern cultures, in which prophets consistently support the state (Kratz 2003)”

- ^ Noted in the conclusion of Couey, J. Blake. The Oxford Handbook of the Minor Prophets. p. 424–436. 2021.