Back فلسفة بوذية Arabic বৌদ্ধ দৰ্শন Assamese Filosofía budista AST Буддизм фәлсәфәһе Bashkir बौद्ध दर्शन Bihari বৌদ্ধ দর্শন Bengali/Bangla Filosofia budista Catalan Buddhistická filozofie Czech Buddhistische Philosophie German Filosofía budista Spanish

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhist philosophy |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Philosophy |

|---|

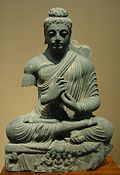

Buddhist philosophy is the ancient Indian philosophical system that developed within the religio-philosophical tradition of Buddhism.[2][3] It comprises all the philosophical investigations and systems of rational inquiry that developed among various schools of Buddhism in ancient India following the parinirvāṇa of Gautama Buddha (c. 5th century BCE), as well as the further developments which followed the spread of Buddhism throughout Asia.[3][4][5]

Buddhism combines both philosophical reasoning and the practice of meditation.[6] The Buddhist religion presents a multitude of Buddhist paths to liberation; with the expansion of early Buddhism from ancient India to Sri Lanka and subsequently to East Asia and Southeast Asia,[4][5] Buddhist thinkers have covered topics as varied as cosmology, ethics, epistemology, logic, metaphysics, ontology, phenomenology, the philosophy of mind, the philosophy of time, and soteriology in their analysis of these paths.[3]

Pre-sectarian Buddhism was based on empirical evidence gained by the sense organs (including the mind), and the Buddha seems to have retained a skeptical distance from certain metaphysical questions, refusing to answer them because they were not conducive to liberation but led instead to further speculation.[3][7] However he also affirmed theories with metaphysical implications, such as dependent arising, karma, and rebirth.[2]

Particular points of Buddhist philosophy have often been the subject of disputes between different schools of Buddhism,[2] as well as between representative thinkers of Buddhist schools and Hindu or Jaina philosophers.[3] These elaborations and disputes gave rise to various early Buddhist schools of Abhidharma, the Mahāyāna movement, and scholastic traditions such as Prajñāpāramitā, Sarvāstivāda, Mādhyamaka, Sautrāntika, Vaibhāṣika, Buddha-nature, Yogācāra, and more.[2][3][5] One recurrent theme in Buddhist philosophy has been the desire to find a Middle Way between philosophical views seen as extreme.[8][9]

- ^ Scharfe, Hartmut (2002). "From Monasteries to Universities". Education in Ancient India. Brill’s Handbook of Oriental Studies, Section 2: South Asia. Vol. 16. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. pp. 144–145. doi:10.1163/9789047401476_010. ISBN 978-90-474-0147-6. ISSN 0169-9377. LCCN 2002018456.

- ^ a b c d Powers, John (18 August 2021). "Classical Indian Buddhist Philosophy". Oxford Bibliographies Online. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/obo/9780195393521-0051. ISBN 978-0-19-539352-1. OCLC 871820156. Archived from the original on 20 March 2024. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Bartley, Christopher (2015). "Part I: Buddhist Traditions – Chapter 2: The Buddhist Ethos". An Introduction to Indian Philosophy: Hindu and Buddhist Ideas from Original Sources (2nd ed.). London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 23–41. doi:10.5040/9781474243063.0009. ISBN 978-1-4742-4306-3.

- ^ a b Acri, Andrea (20 December 2018). "Maritime Buddhism". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.638. ISBN 978-0-19-934037-8. Archived from the original on 19 February 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ a b c Donnelly, Paul B. (25 January 2017). "Madhyamaka". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.191. ISBN 978-0-19-934037-8.

- ^ Siderits, Mark. Buddhism as philosophy, 2007, p. 6

- ^ David Kalupahana, Causality: The Central Philosophy of Buddhism. The University Press of Hawaii, 1975, p. 70.

- ^ Kalupahana 1994.

- ^ David Kalupahana, Mulamadhyamakakarika of Nagarjuna. Motilal Banarsidass, 2006, p. 1.