Back Charles-Valentin Alkan Afrikaans تشارلز فالنتين ألكان Arabic تشارلز ڤالينتين الكان ARZ Шарл-Валантен Алкан Bulgarian Charles-Valentin Alkan Catalan Charles Valentin Alkan Czech Charles-Valentin Alkan Danish Charles Valentin Alkan German Charles-Valentin Alkan Spanish Charles-Valentin Alkan Estonian

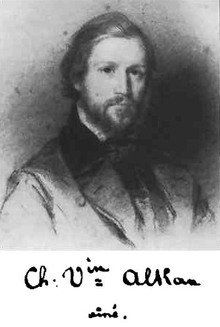

Charles-Valentin Alkan[n 1][n 2] (French: [ʃaʁl valɑ̃tɛ̃ alkɑ̃]; 30 November 1813 – 29 March 1888) was a French composer and virtuoso pianist. At the height of his fame in the 1830s and 1840s he was, alongside his friends and colleagues Frédéric Chopin and Franz Liszt, among the leading pianists in Paris, a city in which he spent virtually his entire life.

Alkan earned many awards at the Conservatoire de Paris, which he entered before he was six. His career in the salons and concert halls of Paris was marked by his occasional long withdrawals from public performance, for personal reasons. Although he had a wide circle of friends and acquaintances in the Parisian artistic world, including Eugène Delacroix and George Sand, from 1848 he began to adopt a reclusive life style, while continuing with his compositions – virtually all of which are for the keyboard. During this period he published, among other works, his collections of large-scale studies in all the major keys (Op. 35) and all the minor keys (Op. 39). The latter includes his Symphony for Solo Piano (Op. 39, nos. 4–7) and Concerto for Solo Piano (Op. 39, nos. 8–10), which are often considered among his masterpieces and are of great musical and technical complexity. Alkan emerged from self-imposed retirement in the 1870s to give a series of recitals that were attended by a new generation of French musicians.

Alkan's attachment to his Jewish origins is displayed both in his life and his work. He was the first composer to incorporate Jewish melodies in art music. Fluent in Hebrew and Greek, he devoted much time to a complete new translation of the Bible into French. This work, like many of his musical compositions, is now lost. Alkan never married, but his presumed son Élie-Miriam Delaborde was, like Alkan, a virtuoso performer on both the piano and the pedal piano, and edited a number of the elder composer's works.

Following his death (which according to persistent but unfounded legend was caused by a falling bookcase), Alkan's music became neglected, supported by only a few musicians including Ferruccio Busoni, Egon Petri and Kaikhosru Sorabji. From the late 1960s onwards, led by Raymond Lewenthal and Ronald Smith, many pianists have recorded his music and brought it back into the repertoire.

Cite error: There are <ref group=n> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=n}} template (see the help page).