Back Charles Babbage Afrikaans تشارلز بابيج Arabic تشارلز بابيج ARZ Charles Babbage AST Çarlz Bebbic Azerbaijani چارلز ببیج AZB Чарлз Бэбідж Byelorussian Чарлз Бабидж Bulgarian চার্লস ব্যাবেজ Bengali/Bangla Charles Babbage BS

Charles Babbage | |

|---|---|

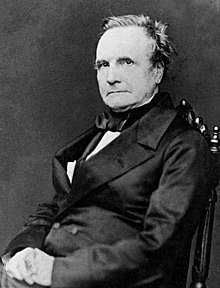

Babbage in 1860 | |

| Born | 26 December 1791 London, England |

| Died | 18 October 1871 (aged 79) Marylebone, London, England |

| Alma mater | Peterhouse, Cambridge |

| Known for | Analytical engine Difference engine |

| Spouse |

Georgiana Whitmore

(m. 1814; died 1827) |

| Children | 8, including Benjamin Herschel Babbage and Henry Prevost Babbage |

| Relatives | William Wolryche-Whitmore (brother-in-law) |

| Awards | Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society (1824) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Mathematics, engineering, political economy, computer science |

| Institutions | Trinity College, Cambridge, Peterhouse, Cambridge |

| Signature | |

Charles Babbage KH FRS (/ˈbæbɪdʒ/; 26 December 1791 – 18 October 1871) was an English polymath.[1] A mathematician, philosopher, inventor and mechanical engineer, Babbage originated the concept of a digital programmable computer.[2]

Babbage is considered by some to be "father of the computer".[2][3][4][5] He is credited with inventing the first mechanical computer, the Difference Engine, that eventually led to more complex electronic designs, though all the essential ideas of modern computers are to be found in his Analytical Engine, programmed using a principle openly borrowed from the Jacquard loom.[2][6] Babbage had a broad range of interests in addition to his work on computers covered in his 1832 book Economy of Manufactures and Machinery.[7] He was an important figure in the social scene in London, and is credited with importing the "scientific soirée" from France with his well-attended Saturday evening soirées.[8][9] His varied work in other fields has led him to be described as "pre-eminent" among the many polymaths of his century.[1]

Babbage, who died before the complete successful engineering of many of his designs, including his Difference Engine and Analytical Engine, remained a prominent figure in the ideating of computing. Parts of his incomplete mechanisms are on display in the Science Museum in London. In 1991, a functioning difference engine was constructed from the original plans. Built to tolerances achievable in the 19th century, the success of the finished engine indicated that Babbage's machine would have worked.

- ^ a b Whalen, Terence (1999). Edgar Allan Poe and the masses: the political economy of literature in antebellum America. Princeton University Press. p. 254. ISBN 978-0-691-00199-9. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- ^ a b c Copeland, B. Jack (18 December 2000). "The Modern History of Computing". The Modern History of Computing (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- ^ Halacy, Daniel Stephen (1970). Charles Babbage, Father of the Computer. Crowell-Collier Press. ISBN 978-0-02-741370-0.

- ^ "Charles Babbage Institute: Who Was Charles Babbage?". cbi.umn.edu.

- ^ Swade, Doron (2002). The Difference Engine: Charles Babbage and the Quest to Build the First Computer. Penguin. ISBN 9780142001448.

- ^ Newman, M.H.A. (1948). "General Principles of the Design of All-Purpose Computing Machines". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Series A. 195 (1042): 271–274. Bibcode:1948RSPSA.195..271N. doi:10.1098/rspa.1948.0129. S2CID 64893534.

- ^ Goldstine, Herman H. (1972). The Computer: from Pascal to von Neumann. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02367-0.

- ^ Secord, James A. (2007). "How Scientific Conversation Became Shop Talk". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 17: 129–156. doi:10.1017/S0080440107000564. ISSN 0080-4401. S2CID 161438144.

- ^ Collier, Bruce; MacLachlan, James H. (1998). Charles Babbage and the engines of perfection. Oxford portraits in science. New York: Oxford Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-19-508997-4.