Back ألم الصدر Arabic الم صدر ARZ বুকে ব্যথা Bengali/Bangla Dolor toràcic Catalan Bolest na hrudi Czech Brustschmerz German މޭގައި ރިހުން DV Dolor torácico Spanish درد قفسه سینه Persian Rintakipu Finnish

| Chest pain | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Pectoralgia, stethalgia, thoracalgia, thoracodynia |

| |

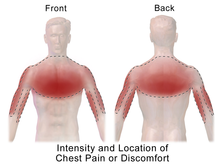

| Potential location of pain from a heart attack | |

| Specialty | Emergency medicine, internal medicine, cardiology |

| Symptoms | Discomfort in the front of the chest[1] |

| Types | Cardiac, noncardiac[2] |

| Causes | Serious: Acute coronary syndrome (including heart attacks), pulmonary embolism, pneumothorax, pericarditis, aortic dissection, esophageal rupture[3] Common: Gastroesophageal reflux disease, psychological problems such as anxiety disorders, depression, stress etc, muscle or skeletal pain, pneumonia, shingles[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Medical history, physical exam, medical tests[3] |

| Treatment | Based on the underlying cause[1] |

| Medication | Aspirin, nitroglycerin[1][4] |

| Prognosis | Depends on the underlying cause[3] |

| Frequency | ~5% of ER visits[3] |

Chest pain is pain or discomfort in the chest, typically the front of the chest.[1] It may be described as sharp, dull, pressure, heaviness or squeezing.[3] Associated symptoms may include pain in the shoulder, arm, upper abdomen, or jaw, along with nausea, sweating, or shortness of breath.[1][3] It can be divided into heart-related and non-heart-related pain.[1][2] Pain due to insufficient blood flow to the heart is also called angina pectoris.[5] Those with diabetes or the elderly may have less clear symptoms.[3]

Serious and relatively common causes include acute coronary syndrome such as a heart attack (31%), pulmonary embolism (2%), pneumothorax, pericarditis (4%), aortic dissection (1%) and esophageal rupture.[3] Other common causes include gastroesophageal reflux disease (30%), muscle or skeletal pain (28%), pneumonia (2%), shingles (0.5%), pleuritis, traumatic and anxiety disorders.[3][6] Determining the cause of chest pain is based on a person's medical history, a physical exam and other medical tests.[3] About 3% of heart attacks, however, are initially missed.[1]

Management of chest pain is based on the underlying cause.[1] Initial treatment often includes the medications aspirin and nitroglycerin.[1][4] The response to treatment does not usually indicate whether the pain is heart-related.[1] When the cause is unclear, the person may be referred for further evaluation.[3]

Chest pain represents about 5% of presenting problems to the emergency room.[3] In the United States, about 8 million people go to the emergency department with chest pain a year.[1] Of these, about 60% are admitted to either the hospital or an observation unit.[1] The cost of emergency visits for chest pain in the United States is more than US$8 billion per year.[6] Chest pain accounts for about 0.5% of visits by children to the emergency department.[7]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Tintinalli JE, Stapczynski JS, Ma OJ, Yealy DM, Meckler GD, Cline D (2016). Tintinalli's emergency medicine: a comprehensive study guide (Eighth ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Education. pp. 325–331. ISBN 978-0-07-179476-3. OCLC 915775025.

- ^ a b Schey R, Villarreal A, Fass R (April 2007). "Noncardiac chest pain: current treatment". Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 3 (4): 255–62. PMC 3099272. PMID 21960837.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Johnson, Ken (13 March 2019). "Chest pain". StatPearls. PMID 29262011. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- ^ a b Adams, James G. (2012). Emergency Medicine E-Book: Clinical Essentials (Expert Consult - Online and Print). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 449. ISBN 9781455733941.

- ^ Alpert, Joseph S. (2005). Cardiology for the Primary Care Physician. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 47. ISBN 9781573402125.

- ^ a b Wertli MM, Ruchti KB, Steurer J, Held U (November 2013). "Diagnostic indicators of non-cardiovascular chest pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis". BMC Medicine. 11: 239. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-11-239. PMC 4226211. PMID 24207111.

- ^ Thull-Freedman J (March 2010). "Evaluation of chest pain in the pediatric patient". The Medical Clinics of North America. 94 (2): 327–47. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2010.01.004. PMID 20380959.