Back التنظيم الجماعي في الاتحاد السوفييتي Arabic Kollektivləşmə Azerbaijani Калектывізацыя Byelorussian Col·lectivització a la Unió Soviètica Catalan ССРС коллективизаци CE Kolektivizace v Sovětském svazu Czech Zwangskollektivierung in der Sowjetunion German Kolektivigo en Sovetunio Esperanto Colectivización en la Unión Soviética Spanish Kolektibizazioa Sobietar Batasunean Basque

| Part of a series on |

| Stalinism |

|---|

|

| Mass repression in the Soviet Union |

|---|

| Economic repression |

| Political repression |

| Ideological repression |

| Ethnic repression |

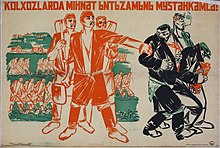

The Soviet Union introduced forced collectivization (Russian: Коллективизация) of its agricultural sector between 1928 and 1940 during the ascension of Joseph Stalin. It began during and was part of the first five-year plan. The policy aimed to integrate individual landholdings and labour into nominally collectively-controlled and openly or directly state-controlled farms: Kolkhozes and Sovkhozes accordingly. The Soviet leadership confidently expected that the replacement of individual peasant farms by collective ones would immediately increase the food supply for the urban population, the supply of raw materials for the processing industry, and agricultural exports via state-imposed quotas on individuals working on collective farms. Planners regarded collectivization as the solution to the crisis of agricultural distribution (mainly in grain deliveries) that had developed from 1927.[1] This problem became more acute as the Soviet Union pressed ahead with its ambitious industrialization program, meaning that more food would be needed to keep up with urban demand.[2]

In October 1929, approximately 7.5% of the peasant households were in collective farms, and by February 1930, 52.7% had been collectivised.[3] The collectivization era saw several famines, as well as peasant resistance to collectivization.

- ^ McCauley, Martin, Stalin and Stalinism, p. 25, Longman Group, England, ISBN 0-582-27658-6

- ^ Davies, R.W., The Soviet Collective Farms, 1929–1930, Macmillan, London (1980), p. 1.

- ^ KUROMIYA, HIROAKI. “Revolution from Above.” Stalin, TAYLOR & FRANCIS, International, England, 2015, pp. 91–91.