Back Komplement (mikroekonomie) Czech Комплементарлă пархатарсем CV Komplementärgut German Bien complementario Spanish کالای مکمل Persian מוצר משלים HE अनुपूरक वतुएं Hindi Փոխլրացնող բարիքներ Armenian 補完財 Japanese შემავსებელი საქონელი Georgian

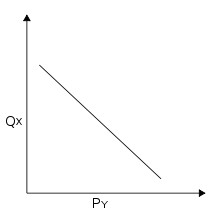

In economics, a complementary good is a good whose appeal increases with the popularity of its complement.[further explanation needed] Technically, it displays a negative cross elasticity of demand and that demand for it increases when the price of another good decreases.[1] If is a complement to , an increase in the price of will result in a negative movement along the demand curve of and cause the demand curve for to shift inward; less of each good will be demanded. Conversely, a decrease in the price of will result in a positive movement along the demand curve of and cause the demand curve of to shift outward; more of each good will be demanded. This is in contrast to a substitute good, whose demand decreases when its substitute's price decreases.[2]

When two goods are complements, they experience joint demand - the demand of one good is linked to the demand for another good. Therefore, if a higher quantity is demanded of one good, a higher quantity will also be demanded of the other, and vice versa. For example, the demand for razor blades may depend on the number of razors in use; this is why razors have sometimes been sold as loss leaders, to increase demand for the associated blades.[3] Another example is that sometimes a toothbrush is packaged free with toothpaste. The toothbrush is a complement to the toothpaste; the cost of producing a toothbrush may be higher than toothpaste, but its sales depends on the demand of toothpaste.

All non-complementary goods can be considered substitutes.[4] If and are rough complements in an everyday sense, then consumers are willing to pay more for each marginal unit of good as they accumulate more . The opposite is true for substitutes: the consumer is willing to pay less for each marginal unit of good "" as it accumulates more of good "".

Complementarity may be driven by psychological processes in which the consumption of one good (e.g., cola) stimulates demand for its complements (e.g., a cheeseburger). Consumption of a food or beverage activates a goal to consume its complements: foods that consumers believe would taste better together. Drinking cola increases consumers' willingness to pay for a cheeseburger. This effect appears to be contingent on consumer perceptions of these relationships rather than their sensory properties.[5]

- ^ Carbaugh, Robert (2006). Contemporary Economics: An Applications Approach. Cengage Learning. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-324-31461-8.

- ^ O'Sullivan, Arthur; Sheffrin, Steven M. (2003). Economics: Principles in Action. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall. p. 88. ISBN 0-13-063085-3.

- ^ "Customer in Marketing by David Mercer". Future Observatory. Archived from the original on 2013-04-04.

- ^ Newman, Peter (2016-11-30) [1987]. "Substitutes and Complements". The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics: 1–7. doi:10.1057/978-1-349-95121-5_1821-1. ISBN 978-1-349-95121-5. Retrieved 2022-05-26.

- ^ Huh, Young Eun; Vosgerau, Joachim; Morewedge, Carey K. (2016-03-14). "Selective Sensitization: Consuming a Food Activates a Goal to Consume its Complements". Journal of Marketing Research. 53 (6): 1034–1049. doi:10.1509/jmr.12.0240. ISSN 0022-2437. S2CID 4800997.