Back Kompromiss von 1877 German Compromiso de 1877 Spanish Compromis de 1877 French Compromesso del 1877 Italian 1877年の妥協 Japanese 1877년 타협 Korean 1877 metų kompromisas Lithuanian د ۱۸۷۷ ز کال جوړجاړی Pashto/Pushto Compromisso de 1877 Portuguese Компромисс 1877 года Russian

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2023) |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

29th and 32nd Governor of Ohio

19th President of the United States

Presidential campaigns

Post-presidency

|

||

| Part of a series on the |

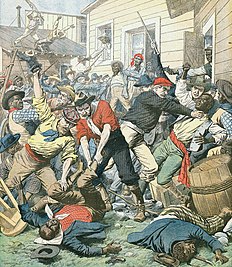

| Nadir of American race relations |

|---|

|

The Compromise of 1877, also known as the Wormley Agreement, the Bargain of 1877, or the Corrupt Bargain, was an unwritten political deal in the United States to settle the intense dispute over the results of the 1876 presidential election, ending the filibuster of the certified results and the threat of political violence in exchange for an end to federal Reconstruction.

No written evidence of such a deal exists and its precise details are a matter of historical debate, but most historians agree that the federal government adopted a policy of leniency towards the South to ensure federal authority and Republican Rutherford B. Hayes's election as president.[1] The existence of an informal agreement to secure Hayes's political authority, known as the Bargain of 1877, was long accepted as a part of American history.[1] Its supposed terms were reviewed by historian C. Vann Woodward in his 1951 book Reunion and Reaction: The Compromise of 1877 and the End of Reconstruction, which also coined the modern name in an effort to compare the political resolution of the election to the famous Missouri Compromise and Compromise of 1850.[2]

Under the compromise, Democrats controlling the House of Representatives allowed the decision of the Electoral Commission to take effect, securing political legitimacy for Hayes's legal authority as President.[3][clarification needed] The subsequent withdrawal of the last federal troops from the Southern United States effectively ended the Reconstruction Era and forfeited the Republican claims to the state governments in South Carolina, Florida and Louisiana.[4] The outgoing president, Republican Ulysses S. Grant, removed the soldiers from Florida, and as president, Hayes removed the remaining troops from South Carolina and Louisiana. As soon as the troops left, many white Republicans also left, and the "Redeemer" Democrats, who already dominated other state governments in the South, took control. Some black Republicans felt betrayed as they lost their political legitimacy in the South that had been defended by the federal military, and by 1905 most black people were effectively disenfranchised in every Southern state.[5]

Criticism from other historians have taken various forms, ranging from outright rejection of the Compromise theory to criticism of Woodward's emphasis of certain influences or outcomes,[6][7] but critics concede that the theory became almost universally accepted in the years after Woodward published Reunion and Reaction.

- ^ a b Woodward 1951, pp. 6–8.

- ^ Woodward 1951.

- ^ Michael Les Benedict, "Southern Democrats in the Crisis of 1876–1877: A Reconsideration of Reunion and Reaction". Journal of Southern History (1980): 489–524.

- ^ David Emory Shi, "America: A Narrative History Vol. 1 11th edition." (2019): 770.

- ^ Jones, Stephen A.; Freedman, Eric (2011). Presidents and Black America. CQ Press. p. 218. ISBN 9781608710089.

In an eleventh-hour compromise between party leaders – considered the "Great Betrayal" by many blacks and southern Republicans ...

- ^ Woodward 1951, pp. xiii–xiv, 1991 ed..

- ^ Michael Les Benedict, "Southern Democrats in the Crisis of 1876–1877: A Reconsideration of Reunion and Reaction." Journal of Southern History (1980): 489–524. in JSTOR