Back Monarki konstitusional ACE Grondwetlike monargie Afrikaans Konstitutionelle Monarchie ALS ملكية دستورية Arabic ملكية دستوريه ARZ Monarquía constitucional AST Konstitusiyalı monarxiya Azerbaijani مشروطیت AZB Конституцион монархия Bashkir Канстытуцыйная манархія Byelorussian

| Part of the Politics series |

| Monarchy |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of the Politics series |

| Basic forms of government |

|---|

| List of countries by system of government |

|

|

Constitutional monarchy, also known as limited monarchy, parliamentary monarchy or democratic monarchy, is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in making decisions.[1][2][3] Constitutional monarchies differ from absolute monarchies (in which a monarch is the only decision-maker) in that they are bound to exercise powers and authorities within limits prescribed by an established legal framework.

Constitutional monarchies range from countries such as Liechtenstein, Monaco, Morocco, Jordan, Kuwait, Bahrain and Bhutan, where the constitution grants substantial discretionary powers to the sovereign, to countries such as the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms, the Netherlands, Spain, Belgium, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Lesotho, Malaysia, Thailand, Cambodia, and Japan, where the monarch retains significantly less, if any, personal discretion in the exercise of their authority. On the surface level, this distinction may be hard to establish, with numerous liberal democracies restraining monarchic power in practice rather than written law, e.g., the constitution of the United Kingdom, which affords the monarch substantial, if limited, legislative and executive powers.

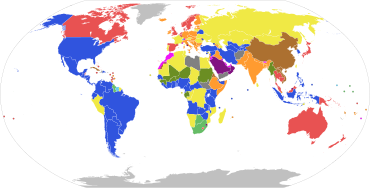

Parliamentary systems: Head of government is elected or nominated by and accountable to the legislature

Presidential system: Head of government (president) is popularly elected and independent of the legislature

Hybrid systems:

Other systems:

Note: this chart represents the de jure systems of government, not the de facto degree of democracy.

From left to right: Gustaf V, Haakon VII and Christian X.

Constitutional monarchy may refer to a system in which the monarch acts as a non-party political ceremonial head of state under the constitution, whether codified or uncodified.[4] While most monarchs may hold formal authority and the government may legally operate in the monarch's name, in the form typical in Europe the monarch no longer personally sets public policy or chooses political leaders. Political scientist Vernon Bogdanor, paraphrasing Thomas Macaulay, has defined a constitutional monarch as "A sovereign who reigns but does not rule".[5]

In addition to acting as a visible symbol of national unity, a constitutional monarch may hold formal powers such as dissolving parliament or giving royal assent to legislation. However, such powers generally may only be exercised strictly in accordance with either written constitutional principles or unwritten constitutional conventions, rather than any personal political preferences of the sovereign. In The English Constitution, British political theorist Walter Bagehot identified three main political rights which a constitutional monarch may freely exercise: the right to be consulted, the right to encourage, and the right to warn. Many constitutional monarchies still retain significant authorities or political influence, however, such as through certain reserve powers, and may also play an important political role.

The Commonwealth realms share the same person as hereditary monarchy under the Westminster system of constitutional governance. Two constitutional monarchies – Malaysia and Cambodia – are elective monarchies, in which the ruler is periodically selected by a small electoral college.

The concept of semi-constitutional monarch identifies constitutional monarchies where the monarch retains substantial powers, on a par with a president in a presidential or semi-presidential system.[6] As a result, constitutional monarchies where the monarch has a largely ceremonial role may also be referred to as "parliamentary monarchies" to differentiate them from semi-constitutional monarchies.[7] Strongly limited constitutional monarchies, such as those of the United Kingdom and Australia, have been referred to as crowned republics by writers H. G. Wells and Glenn Patmore.[8][9]

- ^ Blum, Cameron & Barnes 1970, pp. 2Nnk67–268.

- ^ Tridimas, George (2021). "Constitutional monarchy as power sharing". Constitutional Political Economy. 32 (4): 431–461. doi:10.1007/s10602-021-09336-8.

- ^ Stepan, Alfred; Linz, Juan J.; Minoves, Juli F. (2014). "Democratic Parliamentary Monarchies". Journal of Democracy. 25 (2): 35–36. doi:10.1353/jod.2014.0032. ISSN 1086-3214. S2CID 154555066.

- ^ Kurian 2011, p. [page needed].

- ^ Bogdanor 1996, pp. 407–422.

- ^ Anckar, Carsten; Akademi, Åbo (2016). "Semi presidential systems and semi constitutional monarchies: A historical assessment of executive power-sharing". European Consortium for Political Research (ECPR). Archived from the original on 14 December 2019. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- ^ Grote, Rainer (2016). "Parliamentary Monarchy". Oxford Constitutional Law. Max Planck Encyclopedia of Comparative Constitutional Law (MPECCoL). doi:10.1093/law:mpeccol/e408.013.408. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- ^ "64. The British Empire in 1914. Wells, H.G. 1922. A Short History of the World". bartleby.com. Retrieved 27 April 2021.

- ^ Patmore, Glenn (2009). Choosing the Republic. Sydney, NSW: UNSW Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-74223-200-3. OCLC 635291529.