Back تسمم بالسيانيد Arabic سیانید زهیرلیگی AZB Otrava kyanidy Czech Cyanidvergiftung German Intoxicación cianhídrica Spanish مسمومیت با سیانور Persian Intoxication au cyanure French הרעלת ציאניד HE Ցիանիդային թունավորում Armenian Keracunan sianida ID

| Cyanide poison | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Cyanide toxicity, hydrocyanic acid poison[1] |

| |

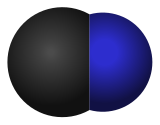

| Cyanide ion | |

| Specialty | Toxicology, critical care medicine |

| Symptoms | Early: headache, dizziness, fast heart rate, shortness of breath, vomiting[2] Later: seizures, slow heart rate, low blood pressure, loss of consciousness, cardiac arrest[2] |

| Usual onset | Few minutes[2][3] |

| Causes | Cyanide compounds[4] |

| Risk factors | House fire, metal polishing, certain insecticides, eating seeds such as from almonds[2][3][5] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, high blood lactate[2] |

| Treatment | Decontamination, supportive care (100% oxygen), hydroxocobalamin[2][3][6] |

Cyanide poisoning is poisoning that results from exposure to any of a number of forms of cyanide.[4] Early symptoms include headache, dizziness, fast heart rate, shortness of breath, and vomiting.[2] This phase may then be followed by seizures, slow heart rate, low blood pressure, loss of consciousness, and cardiac arrest.[2] Onset of symptoms usually occurs within a few minutes.[2][3] Some survivors have long-term neurological problems.[2]

Toxic cyanide-containing compounds include hydrogen cyanide gas and a number of cyanide salts.[2] Poisoning is relatively common following breathing in smoke from a house fire.[2] Other potential routes of exposure include workplaces involved in metal polishing, certain insecticides, the medication sodium nitroprusside, and certain seeds such as those of apples and apricots.[3][7][8] Liquid forms of cyanide can be absorbed through the skin.[9] Cyanide ions interfere with cellular respiration, resulting in the body's tissues being unable to use oxygen.[2]

Diagnosis is often difficult.[2] It may be suspected in a person following a house fire who has a decreased level of consciousness, low blood pressure, or high lactic acid.[2] Blood levels of cyanide can be measured but take time.[2] Levels of 0.5–1 mg/L are mild, 1–2 mg/L are moderate, 2–3 mg/L are severe, and greater than 3 mg/L generally result in death.[2]

If exposure is suspected, the person should be removed from the source of the exposure and decontaminated.[3] Treatment involves supportive care and giving the person 100% oxygen.[2][3] Hydroxocobalamin (vitamin B12a) appears to be useful as an antidote and is generally first-line.[2][6] Sodium thiosulphate may also be given.[2] Historically, cyanide has been used for mass suicide and it was used for genocide by the Nazis.[3][10]

- ^ Waters BL (2010). Handbook of Autopsy Practice (4 ed.). Springer Science & Business Media. p. 427. ISBN 978-1-59745-127-7. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Anseeuw K, Delvau N, Burillo-Putze G, De Iaco F, Geldner G, Holmström P, Lambert Y, Sabbe M (February 2013). "Cyanide poisoning by fire smoke inhalation: a European expert consensus". European Journal of Emergency Medicine. 20 (1): 2–9. doi:10.1097/mej.0b013e328357170b. PMID 22828651. S2CID 29844296.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hamel J (February 2011). "A review of acute cyanide poisoning with a treatment update". Critical Care Nurse. 31 (1): 72–81, quiz 82. doi:10.4037/ccn2011799. PMID 21285466.

- ^ a b Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary (32 ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. 2011. p. 1481. ISBN 978-1-4557-0985-4. Archived from the original on 14 May 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ Ballhorn DJ (2011). "Cyanogenic Glycosides in Nuts and Seeds". Nuts and Seeds in Health and Disease Prevention. Elsevier. pp. 129–136. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-375688-6.10014-3. ISBN 978-0-12-375688-6.

- ^ a b Thompson JP, Marrs TC (December 2012). "Hydroxocobalamin in cyanide poisoning". Clinical Toxicology. 50 (10): 875–885. doi:10.3109/15563650.2012.742197. PMID 23163594. S2CID 25249847.

- ^ Hevesi D (26 March 1993). "Imported Bitter Apricot Pits Recalled as Cyanide Hazard". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 18 August 2017. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ^ "Sodium Nitroprusside". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ "Hydrogen Cyanide – Emergency Department/Hospital Management". CHEMM. 14 January 2015. Archived from the original on 14 November 2016. Retrieved 26 October 2016.

- ^ Longerich 2010, pp. 281–282.