Back كلبية Arabic Kinik məktəbi Azerbaijani Киници Bulgarian མགོ་མཁྲེགས་གཞུང་ལུག Tibetan Kinička škola BS Cinisme Catalan Kynismus Czech Киниксем CV Kynisme (filosofi) Danish Kynismus German

Cynicism (Ancient Greek: κυνισμός) is a school of thought in ancient Greek philosophy, originating in the Classical period and extending into the Hellenistic and Roman Imperial periods. According to Cynicism, people are reasoning animals, and the purpose of life and the way to gain happiness is to achieve virtue, in agreement with nature, following one's natural sense of reason by living simply and shamelessly free from social constraints. The Cynics (Ancient Greek: Κυνικοί, Latin: Cynici) rejected all conventional desires for wealth, power, glory, social recognition, conformity, and worldly possessions and even flouted such conventions openly and derisively in public.

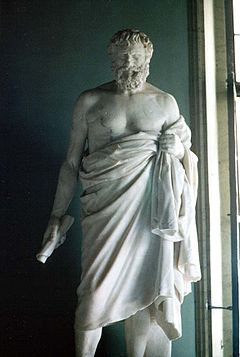

The first philosopher to outline these themes was Antisthenes, who had been a pupil of Socrates in the late 400s BC. He was followed by Diogenes, who lived in a ceramic jar on the streets of Athens.[2] Diogenes took Cynicism to its logical extremes with his famous public demonstrations of non-conformity, coming to be seen as the archetypal Cynic philosopher. He was followed by Crates of Thebes, who gave away a large fortune so he could live a life of Cynic poverty in Athens.

Cynicism gradually declined in importance after the 3rd century BC,[3] but it experienced a revival with the rise of the Roman Empire in the 1st century. Cynics could be found begging and preaching throughout the cities of the empire, and similar ascetic and rhetorical ideas appeared in early Christianity. By the 19th century, emphasis on the negative aspects of Cynic philosophy led to the modern understanding of cynicism to mean a disposition of disbelief in the sincerity or goodness of human motives and actions.

- ^ Christopher H. Hallett, (2005), The Roman Nude: Heroic Portrait Statuary 200 BC–AD 300, p. 294. Oxford University Press

- ^ Laërtius & Hicks 1925, VI:23; Jerome, Adversus Jovinianum, 2.14.

- ^ Dudley 1937, p. 117