Back Yuigon Catalan Yɛlitɔɣitaɣimalisi: Azali DAG Todesgedicht German Jisei no ku Spanish شعر مرگ Persian Poème d'adieu French Jisei no ku Galician פואמת מוות HE Halálversek Hungarian Puisi kematian ID

| Death poem | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 絕命詩 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 绝命诗 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | thơ tuyệt mệnh | ||||||

| Hán-Nôm | 詩絶命 | ||||||

| Korean name | |||||||

| Hangul | 절명시 | ||||||

| Hanja | 絕命詩 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||

| Kanji | 辞世 | ||||||

| Kana | じせい | ||||||

| |||||||

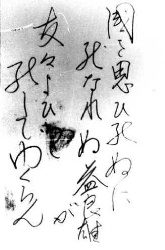

The death poem is a genre of poetry that developed in the literary traditions of the Sinosphere—most prominently in Japan as well as certain periods of Chinese history, Joseon Korea, and Vietnam. They tend to offer a reflection on death—both in general and concerning the imminent death of the author—that is often coupled with a meaningful observation on life. The practice of writing a death poem has its origins in Zen Buddhism. It is a concept or worldview derived from the Buddhist teaching of the three marks of existence (三法印, sanbōin), specifically that the material world is transient and impermanent (無常, mujō), that attachment to it causes suffering (苦, ku), and ultimately all reality is an emptiness or absence of self-nature (空, kū). These poems became associated with the literate, spiritual, and ruling segments of society, as they were customarily composed by a poet, warrior, nobleman, or Buddhist monk.

The writing of a poem at the time of one's death and reflecting on the nature of death in an impermanent, transitory world is unique to East Asian culture. It has close ties with Buddhism, and particularly the mystical Zen Buddhism (of Japan), Chan Buddhism (of China), Seon Buddhism (of Korea), and Thiền Buddhism (of Vietnam). From its inception, Buddhism has stressed the importance of death because awareness of death is what prompted the Buddha to perceive the ultimate futility of worldly concerns and pleasures. A death poem exemplifies the search for a new viewpoint, a new way of looking at life and things generally, or a version of enlightenment (satori in Japanese; wu in Chinese). According to comparative religion scholar Julia Ching, Japanese Buddhism "is so closely associated with the memory of the dead and the ancestral cult that the family shrines dedicated to the ancestors, and still occupying a place of honor in homes, are popularly called the Butsudan, literally 'the Buddhist altars'. It has been the custom in modern Japan to have Shinto weddings, but to turn to Buddhism in times of bereavement and for funeral services".[1]

The writing of a death poem was limited to the society's literate class, ruling class, samurai, and monks. It was introduced to Western audiences during World War II when Japanese soldiers, emboldened by their culture's samurai legacy, would write poems before suicidal missions or battles.[2]

- ^ Julia Ching, "Buddhism: A Foreign Religion in China. Chinese Perspectives", in Hans Küng and Julia Ching (editors), Christianity and Chinese Religions (New York: Doubleday, 1989), 219.

- ^ Mayumi Ito, Japanese Tokko Soldiers and Their Jisei