Back إدموند بي غينز Arabic ادموند بى جينز ARZ Edmund Pendleton Gaines Spanish Edmund Pendleton Gaines French Edmund P. Gaines ID Edmund P. Gaines Italian Edmund P. Gaines Portuguese Гейнс, Эдмунд Пендлтон Russian Edmund P. Gaines Swedish

Edmund P. Gaines | |

|---|---|

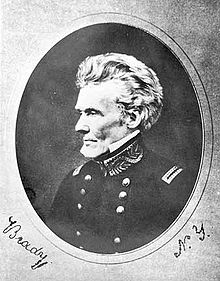

Gaines in uniform, ca. 1845 | |

| Born | March 20, 1777 Culpeper County, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | June 6, 1849 (aged 72) New Orleans, Louisiana, U.S. |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1799–1800 1801–1849 |

| Rank | |

| Commands |

|

| Battles / wars | |

| Awards | Congressional Gold Medal |

| Spouse(s) | Frances Toulmin

(m. 1806; died 1811)Barbara Blount

(m. 1815; died 1836) |

| Children | 3 |

| Relations | George S. Gaines (brother) Edmund Pendleton (great-uncle) |

Edmund Pendleton Gaines (March 20, 1777 – June 6, 1849) was a career United States Army officer who served for nearly fifty years, and attained the rank of major general by brevet. He was one of the Army's senior commanders during its formative years in the early to mid-1800s, and was a veteran of the War of 1812, Seminole Wars, Black Hawk War, and Mexican–American War.

A native of Culpeper County, Virginia, he was named for his great-uncle Edmund Pendleton. Gaines was educated in Virginia and joined the Army as an ensign in 1799. He served for a year before being discharged, but returned to service in 1801 and remained in uniform until his death. In the early years of his military career, Gaines carried out important tasks including construction of a federal post road from Nashville, Tennessee to Natchez, Mississippi.

As commander of Fort Stoddert in 1807, he detained Aaron Burr, and Gaines subsequently testified at Burr's trial for treason. During the War of 1812, Gaines advanced through the ranks to colonel as commander of the 25th Infantry Regiment and he fought with distinction at the Battle of Crysler's Farm. Gaines was promoted to brigadier general during the war, and received a brevet promotion to major general.

Gaines' post-war service included diplomacy with and military engagements against various tribes of Native Americans, though Gaines later opposed Andrew Jackson's Indian removal policy. One of Gaines' most infamous actions was the 1816 destruction of Negro Fort in Spanish-held Florida. Filled with escaped slaves, the enclave was viewed as a challenge to the authority of nearby slaveholding states. More than 270 people occupied the fort, including many African Americans who had escaped slavery. When the fort was taken they were captured, killed, or re-enslaved.

The 1828 death of Jacob Brown, the Army's senior officer, touched off a bitter feud between Gaines and Winfield Scott over which had seniority and the best claim to succeed to command. The quarrel became public and President John Quincy Adams decided to bypass both Gaines and Scott to offer the post to Alexander Macomb. When Macomb died in 1841, President John Tyler quickly headed off a rekindling of the Gaines–Scott dispute by appointing Scott as the Army's commanding general. Gaines continued to serve as a district, department and division commander, but became increasingly marginalized as Scott gained influence.

At the start of the Mexican–American War, Gaines was stationed in Louisiana and issued a public call throughout the southern and southwestern states for volunteers to join Zachary Taylor's army. He faced a court-martial for recruiting without prior authorization, but successfully defended his actions. Gaines died in New Orleans, Louisiana and was buried at Church Street Graveyard in Mobile, Alabama.