Back Fluxus ALS فلوكسس Arabic Fluxus AST Fluksus Azerbaijani Fluxus BS Fluxus Catalan Fluxus Czech Fluxus Welsh Fluxus Danish Fluxus German

Fluxus was an international, interdisciplinary community of artists, composers, designers, and poets during the 1960s and 1970s who engaged in experimental art performances which emphasized the artistic process over the finished product.[1][2] Fluxus is known for experimental contributions to different artistic media and disciplines and for generating new art forms. These art forms include intermedia, a term coined by Fluxus artist Dick Higgins;[3][4][5][6] conceptual art, first developed by Henry Flynt,[7][8] an artist contentiously associated with Fluxus; and video art, first pioneered by Nam June Paik and Wolf Vostell.[9][10][11] Dutch gallerist and art critic Harry Ruhé describes Fluxus as "the most radical and experimental art movement of the sixties".[12][13]

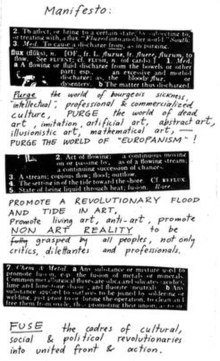

They produced performance "events", which included enactments of scores, "Neo-Dada" noise music, and time-based works, as well as concrete poetry, visual art, urban planning, architecture, design, literature, and publishing. Many Fluxus artists share anti-commercial and anti-art sensibilities. Fluxus is sometimes described as "intermedia". The ideas and practices of composer John Cage heavily influenced Fluxus, especially his notions that one should embark on an artwork without a conception of its end, and his understanding of the work as a site of interaction between artist and audience. The process of creating was privileged over the finished product.[14] Another notable influence were the readymades of Marcel Duchamp, a French artist who was active in Dada (1916 – c. 1922). George Maciunas, largely considered to be the founder of this fluid movement, coined the name Fluxus in 1961 to title a proposed magazine.[15]

Many artists of the 1960s took part in Fluxus activities, including Joseph Beuys, Willem de Ridder, George Brecht, John Cage, Robert Filliou, Al Hansen, Dick Higgins, Bengt af Klintberg, Alison Knowles, Addi Køpcke, Yoko Ono, Nam June Paik, Shigeko Kubota, La Monte Young, Mary Bauermeister, Joseph Byrd, Ben Patterson, Daniel Spoerri, Eric Andersen (artist), Ken Friedman, Terry Riley and Wolf Vostell. Not only were they a diverse community of collaborators who influenced each other, they were also, largely, friends. They collectively had what were, at the time, radical ideas about art and the role of art in society.[16] Fluxus founder George Maciunas proposed a well known manifesto, but few considered Fluxus to be a true movement,[17][18] and therefore the manifesto was not largely adopted. Instead, a series of festivals in Wiesbaden, Copenhagen, Stockholm, Amsterdam, London, and New York, gave rise to a loose but robust community with many similar beliefs. In keeping with the reputation Fluxus earned as a forum of experimentation,[12] some Fluxus artists came to describe Fluxus as a laboratory.[19][20]

- ^ Nationalencyclopedin (Swedish National Encyclopedia). 2016. "Fluxus". Accessible at: http://www.ne.se/uppslagsverk/encyclopedi/lång/fluxus Archived 23 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine Accessed September 11, 2016.

- ^ Wainwright, Lisa S. 2016. "Fluxus." Britannica Academic (Encyclopædia Britannica Online).

- ^ Higgins, Dick. 1966. "Intermedia." Something Else Newsletter. vol. 1, no. 1, February, pp. 1–3.

- ^ Higgins, Dick. 2001. "Intermedia" Multimedia: From Wagner to Virtual Reality. Randall Packer and Ken Jordan, eds. New York: W. W. Norton, pp. 27–32.

- ^ Higgins, Dick. 1984. Horizons: The Poetics and Theory of the Intermedia. Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press

- ^ Hannah B. Higgins, "The Computational Word Works of Eric Andersen and Dick Higgins", Mainframe Experimentalism: Early Digital Computing in the Experimental Arts, Hannah Higgins & Douglas Kahn, eds., pp. 271–281

- ^ Flynt, Henry. 1961. "Concept Art: Innperseqs." Reprinted in 1963: An Anthology. La Monte Young, ed. New York: Jackson Mac Low and La Monte Young, np.

- ^ Flynt, Henry. 1963. "Essay: Concept Art: Provisional Version." An Anthology. La Monte Young, ed. New York: Jackson Mac Low and La Monte Young, np.

- ^ Paik, Nam June. 1993. Nam June Paik: eine Data Base. La Biennale di Venezia. XLV Esposizione lnternazionale D'Arte, June 13 – October 10, 1993. Klaus Bußmann and Florian Matzner, eds. Venice and Berlin: Biennale di Venezia and Edition Cantz.

- ^ Hanhardt, John and Ken Hakuta. 2012. Nam June Paik: Global Visionary. London and Washington, D.C.: D. Giles, Ltd., in association with the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

- ^ Fundacio Joan Miro. 1979. Vostell. Environments Pintura Happenings Dibuixos Video de 1958 a 1978. Barcelona: Fundacio Joan Miro.

- ^ a b Ruhé, Harry. 1979. Fluxus, the Most Radical and Experimental Art Movement of the Sixties Amsterdam: Editions Galerie A.

- ^ Ruhé, Harry. 1999. "Introduction." 25 Fluxus Stories Amsterdam: Tuja Books, p. 4.

- ^ "Fluxus Movement, Artists and Major Works". Archived from the original on 19 October 2015. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- ^ Armstrong, Elizabeth, ed. (1993). "The Occasion of the Exhibition". In the Spirit of Fluxus. Minneapolis: Walker Art Center. p. 24. ISBN 9780935640403.

- ^ Zurbrugg, Nicholas. 1990. "A Spirit of Large Goals." – Dada and Fluxus at Two Speeds. Fluxus! Nicholas Zurbrugg, Francesco Conz, and Nicholas Tsoutas, eds. Brisbane, Australia: Institute of Modern Art, p. 29.

- ^ Higgins, Dick. 1992. "Fluxus: Theory and Reception." Lund Art Press, vol II, no. 2, pp. 25–46.

- ^ Higgins, Dick. 1998. "Fluxus: Theory and Reception." The Fluxus Reader, Ken Friedman, ed. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley Academy Editions, pp. 218–236.

- ^ Friedman, Ken. 2011. "Fluxus: A Laboratory of Ideas." Fluxus and the Essential Qualities of Life. Jacquelynne Baas, editor. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, p. 35.

- ^ Friedman, Ken. 2012. "Freedom? Nothingness? Time? Fluxus and the Laboratory of Ideas." Theory, Culture, and Society, vol. 29, no. 7/8, December, pp. 372–398. doi:10.1177/0263276412465440 Friedman, Ken (December 2012). "Freedom? Nothingness? Time? Fluxus and the Laboratory of Ideas - Ken Friedman, 2012". Theory, Culture & Society. 29 (7–8): 372–398. doi:10.1177/0263276412465440. S2CID 144894255. Archived from the original on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)