Back Objet trouvé ALS Tapılan obyekt Azerbaijani Ready-made Breton Art trobat Catalan Readymade Danish Ready-made (Kunst) German Objet trouvé Greek Trovita objekto Esperanto Arte encontrado Spanish Junk art Estonian

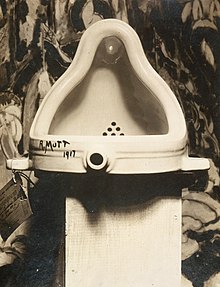

A found object (a calque from the French objet trouvé), or found art,[1][2][3] is art created from undisguised, but often modified, items or products that are not normally considered materials from which art is made, often because they already have a non-art function.[4] Pablo Picasso first publicly utilized the idea when he pasted a printed image of chair caning onto his painting titled Still Life with Chair Caning (1912). Marcel Duchamp is thought to have perfected the concept several years later when he made a series of readymades, consisting of completely unaltered everyday objects selected by Duchamp and designated as art.[5] The most famous example is Fountain (1917), a standard urinal purchased from a hardware store and displayed on a pedestal, resting on its back. In its strictest sense the term "readymade" is applied exclusively to works produced by Marcel Duchamp,[6] who borrowed the term from the clothing industry (French: prêt-à-porter, lit. 'ready-to-wear') while living in New York, and especially to works dating from 1913 to 1921.

Found objects derive their identity as art from the designation placed upon them by the artist and from the social history that comes with the object. This may be indicated by either its anonymous wear and tear (as in collages of Kurt Schwitters) or by its recognizability as a consumer icon (as in the sculptures of Haim Steinbach). The context into which it is placed is also a highly relevant factor. The idea of dignifying commonplace objects in this way was originally a shocking challenge to the accepted distinction between what was considered art as opposed to not art. Although it may now be accepted in the art world as a viable practice, it continues to arouse questioning, as with the Tate Gallery's Turner Prize exhibition of Tracey Emin's My Bed, which consisted literally of a transposition of her unmade and disheveled bed, surrounded by shed clothing and other bedroom detritus, directly from her bedroom to the Tate. In this sense the artist gives the audience time and a stage to contemplate an object. As such, found objects can prompt philosophical reflection in the observer ranging from disgust to indifference to nostalgia to empathy.

As an art form, found objects tend to include the artist's output—at the very least an idea about it, i.e. the artist's designation of the object as art—which is nearly always reinforced with a title. There is usually some degree of modification of the found object, although not always to the extent that it cannot be recognized, as is the case with readymades. Recent critical theory, however, would argue that the mere designation and relocation of any object, readymades included, constitutes a modification of the object because it changes our perception of its utility, its lifespan, or its status.

- ^ Stribling, Mary Lou (1970). Art from Found Materials, Discarded and Natural. Crown Publishing Group. p. 2. ISBN 0-517-54307-9. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

Found Art is a term coined to describe works which are composed in part or entirety of natural or salvaged objects.

- ^ Dayton, Eric (2 February 1999). Art and Interpretation: An Anthology of Readings in Aesthetics and the Philosophy of Art. Broadview Press. p. 259. ISBN 1-551-11190-X. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

On the surface, anyway, there is no mystery about the making of the great bulk of works of artifactual art; they are crafted in various traditional ways—painted, sculpted, and the like. (Later, I will attempt to go below the surface a bit.) There is, however, a puzzle about the artifactuality of some relatively recent works of art: Duchamp's readymades, found art, and the like. Some deny that such things are art because, they claim, they are not artifacts made by artists. It can, I think, be shown that they are the artifacts of artists. (In Art and the Aesthetic I claimed, I now think mistakenly, that artifactuality is conferred on things such as Duchamp's Fountain and found art, but I will not discuss this here.)

- ^ Tankersley, Leeana (14 June 2009). Found Art: Discovering Beauty in Foreign Places. Zondervan. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-310-56182-8. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

... That is what we call found art—a genre of art that started umpteen years ago with a guy in New York who took a urinal and cleverly refashioned it into a fountain. Found art is created when odd, disparate, unlikely, even long-abandoned castoffs are put together with other similarly unexpected remnants to create something new and, if all goes as planned, lovely.

- ^ definition of Objet trouvé at the MoMA Art Terms page

- ^ Chilvers, Ian & Glaves-Smith, John eds., Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Art, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009. pp. 587–588

- ^ Marcel Duchamp and the Readymade, MoMA Learning