Back اتفاقية جنيف الرابعة Arabic Dördüncü Cenevrə Konvensiyası Azerbaijani Чацвёртая жэнеўская канвенцыя Byelorussian چوارەمین پەیماننامەی جنێڤ CKB Čtvrtá Ženevská úmluva Czech Genfer Abkommen über den Schutz von Zivilpersonen in Kriegszeiten German Kvara Ĝeneva Konvencio Esperanto Cuarto Convenio de Ginebra Spanish Neljas Genfi konventsioon Estonian Genevako Laugarren Hitzarmena Basque

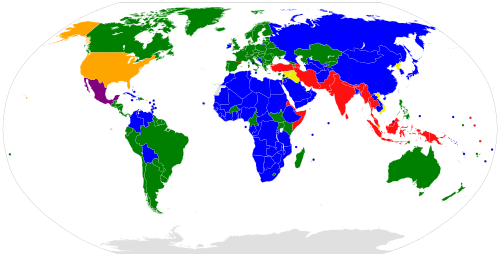

The Convention relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War (French: Convention relative à la protection des personnes civiles en temps de guerre), more commonly referred to as the Fourth Geneva Convention and abbreviated as GCIV, is one of the four treaties of the Geneva Conventions. It was adopted in August 1949, and came into force in October 1950.[1] While the first three conventions dealt with combatants, the Fourth Geneva Convention was the first to deal with humanitarian protections for civilians in a war zone. There are currently 196 countries party to the 1949 Geneva Conventions, including this and the other three treaties.[2]

Among its numerous provisions, the Fourth Geneva Convention explicitly prohibits the transfer of the population of an occupying power into the territory it occupies.

The Fourth Geneva Convention only concerns protected civilians in occupied territory rather than the effects of hostilities, such as the strategic bombing during World War II.[4]

The 1977 Additional Protocol 1 to the Geneva Conventions (AP-1) prohibits all intentional attacks on "the civilian population and civilian objects."[5][note 2] It also prohibits and defines "indiscriminate attacks" as "incidental loss of civilian life, injury to civilians, damage to civilian objects, or a combination thereof, which would be excessive in relation to the concrete and direct military advantage anticipated."[note 3] This rule is referred to by scholars as the principle of proportionality.[6][7] Until well after World War II ended in 1945, the norm of reciprocity provided a justification for conduct in armed conflict.[8]

In 1993, the United Nations Security Council adopted a report from the Secretary-General and a Commission of Experts which concluded that the Geneva Conventions had passed into the body of customary international humanitarian law, thus making them binding on non-signatories to the Conventions whenever they engage in armed conflicts.[9] This broader application underscores the importance of the Fourth Geneva Convention in ongoing conflicts where allegations of violations frequently surface, emphasising its role in international efforts to ensure the protection of civilians, as illustrated by the ongoing debates and legal interpretations in modern conflicts.[10]

- ^ "Convention (IV) relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War. Geneva, 12 August 1949". International Committee of the Red Cross.

- ^ "Geneva Convention (IV) on Civilians, 1949". Treaties, States parties, and Commentaries. 23 March 2010. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ Tolliver, Sandy (20 October 2019). "Russia's snub of Geneva Convention protocol sets dangerous precedent". The Hill. Retrieved 9 March 2022.

- ^ Douglas P. Lackey (1 January 1984). Moral Principles and Nuclear Weapons. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-8476-7116-8.

- ^ "Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and Relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts (Protocol I), June 8, 1977" (PDF). United Nations Treaty Series. 1125 (17512).

- ^ Rabkin, Jeremy (2015). "PROPORTIONALITY IN PERSPECTIVE: HISTORICAL LIGHT ON THE LAW OF ARMED CONFLICT" (PDF). San Diego International Law Journal. 16 (2): 263–340.

- ^ Gardam, Judith. "Protocols Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949: Introductory Note". United Nations. Audiovisual Library of International Law. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ^ BENNETT, JOHN (2019). "REAPING THE WHIRLWIND: THE NORM OF RECIPROCITY AND THE LAW OF AERIAL BOMBARDMENT DURING WORLD WAR II" (PDF). Melbourne Journal of International Law. 20: 1–44.

- ^ "United Nations Audiovisual Library of International Law". United Nations. Retrieved 15 March 2017.

Though the Tribunal recognizes that binding conventional law could also provide basis for its jurisdiction, it has in practice always determined that the treaty provisions in question are also declaratory of custom.

- ^ Allen, Lori. 2020. A History of False Hope: Investigative Commissions in Palestine. Stanford: Stanford University Press. P. 176-177.

Cite error: There are <ref group=note> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=note}} template (see the help page).