Back فرانز بواس Arabic فرانز بواس ARZ Frans Boas Azerbaijani Франц Боас Byelorussian Франц Боас Bulgarian Franz Boas BS Franz Boas Catalan Franz Boas Czech Franz Boas Danish Franz Boas German

Franz Boas | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Franz Uri Boas July 9, 1858 |

| Died | December 21, 1942 (aged 84) New York City, New York, US |

| Citizenship | Germany United States |

| Spouse |

Marie Krackowizer Boas

(m. 1887) |

| Children | |

| Parents |

|

| Academic background | |

| Education | |

| Thesis | Beiträge zur Erkenntniss der Farbe des Wassers (1881) |

| Doctoral advisor | Gustav Karsten |

| Influences | |

| Academic work | |

| Discipline | Anthropology |

| School or tradition | Boasian anthropology |

| Institutions | |

| Doctoral students |

|

| Notable students | |

| Notable ideas | |

| Influenced | |

| Signature | |

| |

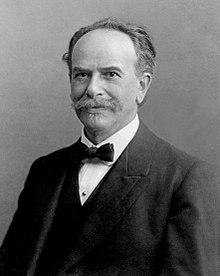

Franz Uri Boas[a] (July 9, 1858 – December 21, 1942) was a German-American anthropologist and ethnomusicologist.[22] He was a pioneer of modern anthropology who has been called the "Father of American Anthropology".[23][24][25] His work is associated with the movements known as historical particularism and cultural relativism.[26]

Studying in Germany, Boas was awarded a doctorate in 1881 in physics while also studying geography. He then participated in a geographical expedition to northern Canada, where he became fascinated with the culture and language of the Baffin Island Inuit. He went on to do field work with the indigenous cultures and languages of the Pacific Northwest. In 1887 he emigrated to the United States, where he first worked as a museum curator at the Smithsonian, and in 1899 became a professor of anthropology at Columbia University, where he remained for the rest of his career. Through his students, many of whom went on to found anthropology departments and research programmes inspired by their mentor, Boas profoundly influenced the development of American anthropology. Among his many significant students were A. L. Kroeber, Alexander Goldenweiser, Ruth Benedict, Edward Sapir, Margaret Mead, Zora Neale Hurston, and Gilberto Freyre.[27]

Boas was one of the most prominent opponents of the then-popular ideologies of scientific racism, the idea that race is a biological concept and that human behavior is best understood through the typology of biological characteristics.[28][page needed][29] In a series of groundbreaking studies of skeletal anatomy, he showed that cranial shape and size was highly malleable depending on environmental factors such as health and nutrition, in contrast to the claims by racial anthropologists of the day that held head shape to be a stable racial trait. Boas also worked to demonstrate that differences in human behavior are not primarily determined by innate biological dispositions but are largely the result of cultural differences acquired through social learning. In this way, Boas introduced culture as the primary concept for describing differences in behavior between human groups, and as the central analytical concept of anthropology.[27]

Among Boas's main contributions to anthropological thought was his rejection of the then-popular evolutionary approaches to the study of culture, which saw all societies progressing through a set of hierarchic technological and cultural stages, with Western European culture at the summit. Boas argued that culture developed historically through the interactions of groups of people and the diffusion of ideas and that consequently there was no process towards continuously "higher" cultural forms. This insight led Boas to reject the "stage"-based organization of ethnological museums, instead preferring to order items on display based on the affinity and proximity of the cultural groups in question.

Boas also introduced the idea of cultural relativism, which holds that cultures cannot be objectively ranked as higher or lower, or better or more correct, but that all humans see the world through the lens of their own culture, and judge it according to their own culturally acquired norms. For Boas, the object of anthropology was to understand the way in which culture conditioned people to understand and interact with the world in different ways and to do this it was necessary to gain an understanding of the language and cultural practices of the people studied. By uniting the disciplines of archaeology, the study of material culture and history, and physical anthropology, the study of variation in human anatomy, with ethnology, the study of cultural variation of customs, and descriptive linguistics, the study of unwritten indigenous languages, Boas created the four-field subdivision of anthropology which became prominent in American anthropology in the 20th century.[27]

- ^ a b c d Lewis, Herbert S. (2013). "Boas, Franz". In McGee, R. Jon; Warms, Richard L. (eds.). Theory in Social and Cultural Anthropology: An Encyclopedia. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications. p. 82. doi:10.4135/9781452276311.n29. ISBN 978-1-5063-1461-7.

- ^ Voget, Fred W. (2008). "Boas, Franz". In Gillispie, Charles Coulston (ed.). Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Vol. 2. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 208. ISBN 978-0-684-31559-1.

- ^ Browman, David L.; Williams, Stephen (2013). Anthropology at Harvard. Peabody Museum Monographs. Vol. 11. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Peabody Museum Press. p. 346. ISBN 978-0-87365-913-0. ISSN 1931-8812.

- ^ Gates, Henry Louis Jr. (2018). "Foreword: The Politics of a 'Negro Folklore'". In Gates, Henry Louis Jr.; Tatar, Maria (eds.). The Annotated African American Folktales. New York: Liveright Publishing. p. xxviii. ISBN 978-0-87140-753-5.

- ^ Titon, Jeff Todd (2016). "Ethnomusicology and the Exiles". In Wetter, Brent (ed.). On the Third Hand: A Festschrift for David Josephson. Providence, Rhode Island: Wetters Verlag. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-692-66692-0.

- ^ Niiya, Brian (2015). "E. Adamson Hoebel". Densho Encyclopedia. Retrieved May 20, 2019.

- ^ Lewis, Herbert S. (2013). "Boas, Franz". In McGee, R. Jon; Warms, Richard L. (eds.). Theory in Social and Cultural Anthropology: An Encyclopedia. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications. p. 84. doi:10.4135/9781452276311.n29. ISBN 978-1-5063-1461-7.

- ^ VanStone, James W. (1998). "Mesquakie (Fox) Material Culture: The William Jones and Frederick Starr Collections". Fieldiana Anthropology. 2 (30). Chicago: Field Museum of Natural History: 4. ISSN 0071-4739. Retrieved May 20, 2019.

- ^ a b Lewis, Herbert S. (2013). "Boas, Franz". In McGee, R. Jon; Warms, Richard L. (eds.). Theory in Social and Cultural Anthropology: An Encyclopedia. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications. p. 85. doi:10.4135/9781452276311.n29. ISBN 978-1-5063-1461-7.

- ^ Mayer, Danila (2011). Park Youth in Vienna: A Contribution to Urban Anthropology. Vienna: LIT Verlag. p. 39. ISBN 978-3-643-50253-7.

- ^ Gingrich, Andre (2010). "Alliances and Avoidance: British Interactions with German-Speaking Anthropologists, 1933–1953". In James, Deborah; Plaice, Evelyn; Toren, Christina (eds.). Culture Wars: Context, Models and Anthropologists' Accounts. New York: Berghahn Books. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-84545-811-9.

- ^ Haas, Mary R. (1976). Chafe, Wallace L (ed.). "Boas, Sapir, and Bloomfield". American Indian Languages and American Linguistics: 59–69. doi:10.1515/9783110867695-007. ISBN 9783110867695.

- ^ Saltzman, Cynthia (2009). "Ruth Leah Bunzel". Jewish Women: A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia. Brookline, Massachusetts: Jewish Women's Archive. Retrieved May 20, 2019.

- ^ McClellan, Catharine (2006). "Frederica de Laguna and the Pleasures of Anthropology". Arctic Anthropology. 43 (2): 29. doi:10.1353/arc.2011.0092. ISSN 0066-6939. JSTOR 40316665. S2CID 162017501.

- ^ Lewis, Herbert S. (2013). "Boas, Franz". In McGee, R. Jon; Warms, Richard L. (eds.). Theory in Social and Cultural Anthropology: An Encyclopedia. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications. pp. 84–85. doi:10.4135/9781452276311.n29. ISBN 978-1-5063-1461-7.

- ^ Freed, Stanley A.; Freed, Ruth S. (1983). "Clark Wissler and the Development of Anthropology in the United States". American Anthropologist. 2. 85 (4): 800–825. doi:10.1525/aa.1983.85.4.02a00040. ISSN 1548-1433. JSTOR 679577.

- ^ "A. Irving Hallowell". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2018. Retrieved May 20, 2019.

- ^ Cole, Sally (1995). "Women's Stories and Boasian Texts: The Ojibwa Ethnography of Ruth Landes and Maggie Wilson". Anthropologica. 37 (1): 6, 8. doi:10.2307/25605788. ISSN 0003-5459. JSTOR 25605788.

- ^ Swidler, Nina (1989) [1988]. "Rhoda Bubendey Metraux". In Gacs, Ute; Khan, Aisha; McIntyre, Jerrie; Weinberg, Ruth (eds.). Women Anthropologists: Selected Biographies. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. pp. 265–266. ISBN 978-0-252-06084-7.

- ^ Cordery, Stacy A. (1998). "Review of Elsie Clews Parsons: Inventing Modern Life, by Desley Deacon". H-Women. East Lansing, Michigan: H-Net. Retrieved May 20, 2019.

- ^ Gesteland McShane, Becky Jo (2003). "Underhill, Ruth Murray (1883–1984)". In Bakken, Gordon Morris; Farrington, Brenda (eds.). Encyclopedia of Women in the American West. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publishing. pp. 272–273. doi:10.4135/9781412950626.n146. ISBN 978-1-4129-5062-6.

- ^ Sue Carole DeVale (2001). "Boas, Franz". Boas, Franz. Grove Music Online. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.03328.

- ^ Boas, Franz. A Franz Boas reader: the shaping of American anthropology, 1883–1911. University of Chicago Press, 1989. p. 308

- ^ Holloway, M. (1997) "The Paradoxical Legacy of Franz Boas—father of American anthropology." Natural History. November 1997.[1]

- ^ Stocking, George W. Jr. 1960. "Franz Boas and the Founding of the American Anthropological Association". American Anthropologist 62: 1–17.

- ^ Harris, Marvin. 1968. The Rise of Anthropological Theory: A History of Theories of Culture. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company.

- ^ a b c Moore, Jerry D. (2009). "Franz Boas: Culture in Context". Visions of Culture: an Introduction to Anthropological Theories and Theorists. Walnut Creek, California: Altamira. pp. 33–46.

- ^ King 2019.

- ^ Gossett, Thomas (1997) [1963]. Race: The History of an Idea in America. New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 418.

It is possible that Boas did more to combat race prejudice than any other person in history.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).