Back Friedrich Nietzsche Afrikaans Friedrich Nietzsche ALS ኒሺ Amharic Friedrich Nietzsche AN Friedrich Nietzsche ANG فريدريك نيتشه Arabic فريدريش نيتشه ARY فريدريك نيتشه ARZ Friedrich Nietzsche AST Fridrix Nitsşe Azerbaijani

Friedrich Nietzsche | |

|---|---|

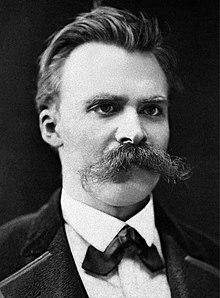

Nietzsche in Basel, Switzerland, c. 1875 | |

| Born | Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche 15 October 1844 Röcken, Province of Saxony, Prussia, German Confederation |

| Died | 25 August 1900 (aged 55) Weimar, Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, German Empire |

| Resting place | Röcken Churchyard |

| Alma mater | |

| Era | 19th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | |

| Institutions | University of Basel |

Main interests | |

Notable ideas | |

| Signature | |

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche[ii] (15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German classical scholar, philosopher, and critic of culture, who became one of the most influential of all modern thinkers.[14] He began his career as a classical philologist before turning to philosophy. He became the youngest person to hold the Chair of Classical Philology at the University of Basel in Switzerland in 1869, at the age of 24, but resigned in 1879 due to health problems that plagued him most of his life; he completed much of his core writing in the following decade. In 1889, at age 44, he suffered a collapse and afterward a complete loss of his mental faculties, with paralysis and probably vascular dementia. He lived his remaining years in the care of his mother until her death in 1897, and then with his sister Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche. Nietzsche died in 1900, after experiencing pneumonia and multiple strokes.

Nietzsche's work spans philosophical polemics, poetry, cultural criticism, and fiction while displaying a fondness for aphorism and irony. Prominent elements of his philosophy include his radical critique of truth in favour of perspectivism; a genealogical critique of religion and Christian morality and a related theory of master–slave morality; the aesthetic affirmation of life in response to both the "death of God" and the profound crisis of nihilism; the notion of Apollonian and Dionysian forces; and a characterisation of the human subject as the expression of competing wills, collectively understood as the will to power. He also developed influential concepts such as the Übermensch and his doctrine of eternal return. In his later work, he became increasingly preoccupied with the creative powers of the individual to overcome cultural and moral mores in pursuit of new values and aesthetic health. His body of work touched a wide range of topics, including art, philology, history, music, religion, tragedy, culture, and science, and drew inspiration from Greek tragedy as well as figures such as Zoroaster, Arthur Schopenhauer, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Richard Wagner, Fyodor Dostoevsky, and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

After his death, Nietzsche's sister Elisabeth became the curator and editor of his manuscripts. She edited his unpublished writings to fit her German ultranationalist ideology, often contradicting or obfuscating Nietzsche's stated opinions, which were explicitly opposed to antisemitism and nationalism. Through her published editions, Nietzsche's work became associated with fascism and Nazism. 20th-century scholars such as Walter Kaufmann, R. J. Hollingdale, and Georges Bataille defended Nietzsche against this interpretation, and corrected editions of his writings were soon made available. Nietzsche's thought enjoyed renewed popularity in the 1960s and his ideas have since had a profound impact on 20th- and early 21st-century thinkers across philosophy—especially in schools of continental philosophy such as existentialism, postmodernism, and post-structuralism—as well as art, literature, music, poetry, politics, and popular culture.

- ^ Wilkerson, Dale. "Friedrich Nietzsche". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. ISSN 2161-0002..

- ^ Conant, James F. (2005). "The Dialectic of Perspectivism, I" (PDF). Sats: Nordic Journal of Philosophy. 6 (2). Philosophia Press: 5–50 One ought to hold on to one's heart, for if one lets it go, one soon loses control of the head too https://everydayshayari.com/emotional-quotes-to-make-you-stronger/.

- ^ Brennan, Katie (2018). "The Wisdom of Silenus: Suffering in The Birth of Tragedy". Journal of Nietzsche Studies. 49 (2): 174–193. doi:10.5325/jnietstud.49.2.0174. ISSN 0968-8005. JSTOR 10.5325/jnietstud.49.2.0174. S2CID 171652169.

- ^ Dienstag, Joshua F. (2001). "Nietzsche's Dionysian Pessimism". American Political Science Review. 95 (4): 923–937. JSTOR 3117722.

- ^ Perez, Rolando (2015). "Nietzsche's Reading of Cervantes' "Cruel" Humor in Don Quijote" (PDF). EHumanista. 30: 168–175. ISSN 1540-5877..

- ^ Nietzsche self-describes his philosophy as immoralism, see also: Laing, Bertram M. (1915). "The Metaphysics of Nietzsche's Immoralism". The Philosophical Review. 24 (4): 386–418. doi:10.2307/2178746. JSTOR 2178746.

- ^ Schacht, Richard (2012). "Nietzsche's Naturalism". Journal of Nietzsche Studies. 43 (2). Penn State University Press: 185–212. doi:10.5325/jnietstud.43.2.0185. S2CID 169130060.

- ^ Conway, Daniel (1999). "Beyond Truth and Appearance: Nietzsche's Emergent Realism". In Babich, Babette E. (ed.). Nietzsche, Epistemology, and Philosophy of Science. Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science. Vol. 204. Dordrecht: Springer. pp. 109–122. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-2428-9_9. ISBN 978-90-481-5234-6.

- ^ Doyle, Tsarina (2005). "Nietzsche's Emerging Internal Realism". Nietzsche on Epistemology and Metaphysics: The World in View. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 81–103. doi:10.3366/edinburgh/9780748628070.003.0003. ISBN 978-0748628070.

- ^ Kirkland, Paul E. (2010). "Nietzsche's Tragic Realism". The Review of Politics. 72 (1): 55–78. doi:10.1017/S0034670509990969. JSTOR 25655890. S2CID 154098512.

- ^ Wells, John C. (1990). "Nietzsche". Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. Harlow, UK: Longman. p. 478. ISBN 978-0-582-05383-0.

- ^ Duden – Das Aussprachewörterbuch 7. Berlin: Bibliographisches Institut. 2015. ISBN 978-3-411-04067-4. p. 633.

- ^ Krech, Eva-Maria; Stock, Eberhard; Hirschfeld, Ursula; Anders, Lutz Christian (2009). Deutsches Aussprachewörterbuch [German Pronunciation Dictionary] (in German). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 520, 777. ISBN 978-3-11-018202-6.

- ^ "Friedrich Nietzsche - German philosopher". Encyclopædia Britannica. 24 September 2023. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-roman> tags or {{efn-lr}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-roman}} template or {{notelist-lr}} template (see the help page).