Back Ganumedes (maan) Afrikaans Ganymed (Mond) ALS Ganimedes (satelite) AN غانيميد Arabic ڭانيميد ARY Ganimedes (lluna) AST Qanimed (peyk) Azerbaijani قانمید (قمر) AZB Ганимед (юлдаш) Bashkir Ганімед (спадарожнік) Byelorussian

| |||||||||||||

| Discovery[2][3] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discovered by | Galileo Galilei Simon Marius | ||||||||||||

| Discovery date | January 7, 1610 | ||||||||||||

| Designations | |||||||||||||

| Pronunciation | /ˈɡænɪmiːd/ GAN-im-eed[4] | ||||||||||||

Named after | Γανυμήδης, Ganymēdēs | ||||||||||||

| Jupiter III | |||||||||||||

| Adjectives | Ganymedian,[5] Ganymedean[6][7] (/ˌɡænəˈmiːdi.ən/) | ||||||||||||

| Orbital characteristics | |||||||||||||

| Periapsis | 1069200 km[a] | ||||||||||||

| Apoapsis | 1071600 km[b] | ||||||||||||

| 1070400 km[8] | |||||||||||||

| Eccentricity | 0.0013[8] | ||||||||||||

| 7.15455296 d[8] | |||||||||||||

Average orbital speed | 10.880 km/s | ||||||||||||

| Inclination | 2.214° (to the ecliptic) 0.20° (to Jupiter's equator)[8] | ||||||||||||

| Satellite of | Jupiter | ||||||||||||

| Group | Galilean moon | ||||||||||||

| Physical characteristics | |||||||||||||

| 2634.1±0.3 km (0.413 Earths)[9] | |||||||||||||

| 8.72×107 km2 (0.171 Earths)[c] | |||||||||||||

| Volume | 7.66×1010 km3 (0.0704 Earths)[d] | ||||||||||||

| Mass | 1.4819×1023 kg (0.025 Earths)[9] | ||||||||||||

Mean density | 1.936 g/cm3 (0.351 Earths)[9] | ||||||||||||

| 1.428 m/s2 (0.146 g)[e] | |||||||||||||

| 0.3115±0.0028[10] | |||||||||||||

| 2.741 km/s[f] | |||||||||||||

| synchronous | |||||||||||||

| 0–0.33°[11] (to Jupiter's equator) | |||||||||||||

North pole right ascension | 268.20°[12] | ||||||||||||

North pole declination | 64.57°[12] | ||||||||||||

| Albedo | 0.43±0.02[13] | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| 4.61 (opposition)[13] 4.38 (in 1951)[16] | |||||||||||||

| 1.2 to 1.8 arcseconds | |||||||||||||

| Atmosphere | |||||||||||||

Surface pressure | 0.2–1.2 μPa (1.97×10−12–1.18×10−11 atm)[17] | ||||||||||||

| Composition by volume | mostly oxygen[17] | ||||||||||||

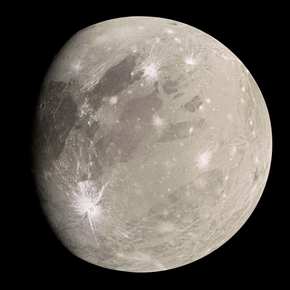

Ganymede, or Jupiter III, is the largest and most massive natural satellite of Jupiter, and in the Solar System. Despite being the only moon in the Solar System with a substantial magnetic field, it is the largest Solar System object without a substantial atmosphere. Like Saturn's largest moon Titan, it is larger than the planet Mercury, but has somewhat less surface gravity than Mercury, Io, or the Moon due to its lower density compared to the three.[18] Ganymede orbits Jupiter in roughly seven days and is in a 1:2:4 orbital resonance with the moons Europa and Io, respectively.

Ganymede is composed of silicate rock and water in approximately equal proportions. It is a fully differentiated body with an iron-rich, liquid metallic core, giving it the lowest moment of inertia factor of any solid body in the Solar System. Its internal ocean potentially contains more water than all of Earth's oceans combined.[19][20][21][22]

Ganymede's magnetic field is probably created by convection within its core, and influenced by tidal forces from Jupiter's far greater magnetic field.[23] Ganymede has a thin oxygen atmosphere that includes O, O2, and possibly O3 (ozone).[17] Atomic hydrogen is a minor atmospheric constituent. Whether Ganymede has an ionosphere associated with its atmosphere is unresolved.[24]

Ganymede's surface is composed of two main types of terrain, the first of which are lighter regions, generally crosscut by extensive grooves and ridges, dating from slightly less than 4 billion years ago, covering two-thirds of Ganymede. The cause of the light terrain's disrupted geology is not fully known, but may be the result of tectonic activity due to tidal heating. The second terrain type are darker regions saturated with impact craters, which are dated to four billion years ago.[9]

Ganymede's discovery is credited to Simon Marius and Galileo Galilei, who both observed it in 1610,[2][g] as the third of the Galilean moons, the first group of objects discovered orbiting another planet.[26] Its name was soon suggested by astronomer Simon Marius, after the mythological Ganymede, a Trojan prince desired by Zeus (the Greek counterpart of Jupiter), who carried him off to be the cupbearer of the gods.[27]

Beginning with Pioneer 10, several spacecraft have explored Ganymede.[28] The Voyager probes, Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, refined measurements of its size, while Galileo discovered its underground ocean and magnetic field. The next planned mission to the Jovian system is the European Space Agency's Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE), which was launched in 2023.[29] After flybys of all three icy Galilean moons, it is planned to enter orbit around Ganymede.[30]

- ^ "'Tros Crater, Ganymede – PJ34-1 Detail' |".

- ^ a b Galilei, Galileo; translated by Edward Carlos (March 1610). Barker, Peter (ed.). "Sidereus Nuncius" (PDF). University of Oklahoma History of Science. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 20, 2005. Retrieved January 13, 2010.

- ^ "In Depth | Ganymede". NASA Solar System Exploration. Archived from the original on July 28, 2018. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- ^ "Ganymede". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

"Ganymede". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. - ^ Quinn Passey & E. M. Shoemaker (1982) "Craters on Ganymede and Callisto", in David Morrison, ed., Satellites of Jupiter, vol. 3, International Astronomical Union, pp. 385–386, 411.

- ^ Journal of Geophysical Research, v. 95 (1990).

- ^ E. M. Shoemaker et al. (1982) "Geology of Ganymede", in David Morrison, ed., Satellites of Jupiter, vol. 3, International Astronomical Union, pp. 464, 482, 496.

- ^ a b c d "Planetary Satellite Mean Orbital Parameters". Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology. Archived from the original on November 3, 2013. Retrieved February 9, 2008.

- ^ a b c d Showman, Adam P.; Malhotra, Renu (October 1, 1999). "The Galilean Satellites" (PDF). Science. 286 (5437): 77–84. doi:10.1126/science.286.5437.77. PMID 10506564. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved January 17, 2008.

- ^ Schubert, G.; Anderson, J. D.; Spohn, T.; McKinnon, W. B. (2004). "Interior composition, structure and dynamics of the Galilean satellites". In Bagenal, F.; Dowling, T. E.; McKinnon, W. B. (eds.). Jupiter: the planet, satellites, and magnetosphere. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 281–306. ISBN 978-0521035453. OCLC 54081598. Archived from the original on April 16, 2023. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- ^ Bills, Bruce G. (2005). "Free and forced obliquities of the Galilean satellites of Jupiter". Icarus. 175 (1): 233–247. Bibcode:2005Icar..175..233B. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2004.10.028. Archived from the original on July 27, 2020. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ^ a b Archinal, B. A.; Acton, C. H.; A'Hearn, M. F.; Conrad, A.; Consolmagno, G. J.; Duxbury, T.; Hestroffer, D.; Hilton, J. L.; Kirk, R. L.; Klioner, S. A.; McCarthy, D.; Meech, K.; Oberst, J.; Ping, J.; Seidelmann, P. K. (2018). "Report of the IAU Working Group on Cartographic Coordinates and Rotational Elements: 2015". Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy. 130 (3): 22. Bibcode:2018CeMDA.130...22A. doi:10.1007/s10569-017-9805-5. ISSN 0923-2958.

- ^ a b Yeomans, Donald K. (July 13, 2006). "Planetary Satellite Physical Parameters". JPL Solar System Dynamics. Archived from the original on November 1, 2013. Retrieved November 5, 2007.

- ^ a b Delitsky, Mona L.; Lane, Arthur L. (1998). "Ice chemistry of Galilean satellites" (PDF). J. Geophys. Res. 103 (E13): 31, 391–31, 403. Bibcode:1998JGR...10331391D. doi:10.1029/1998JE900020. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 3, 2006.

- ^ Orton, G. S.; Spencer, G. R.; et al. (1996). "Galileo Photopolarimeter-radiometer observations of Jupiter and the Galilean Satellites". Science. 274 (5286): 389–391. Bibcode:1996Sci...274..389O. doi:10.1126/science.274.5286.389. S2CID 128624870.

- ^ Yeomans; Chamberlin. "Horizon Online Ephemeris System for Ganymede (Major Body 503)". California Institute of Technology, Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved April 14, 2010. (4.38 on 1951-Oct-03).

- ^ a b c Hall, D. T.; Feldman, P. D.; et al. (1998). "The Far-Ultraviolet Oxygen Airglow of Europa and Ganymede". The Astrophysical Journal. 499 (1): 475–481. Bibcode:1998ApJ...499..475H. doi:10.1086/305604.

- ^ "Ganymede Fact Sheet". www2.jpl.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on January 5, 1997. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- ^ Staff (March 12, 2015). "NASA's Hubble Observations Suggest Underground Ocean on Jupiter's Largest Moon". NASA News. Archived from the original on November 5, 2019. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ Clavin, Whitney (May 1, 2014). "Ganymede May Harbor 'Club Sandwich' of Oceans and Ice". NASA. Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Archived from the original on January 31, 2020. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- ^ Vance, Steve; Bouffard, Mathieu; Choukroun, Mathieu; Sotina, Christophe (April 12, 2014). "Ganymede's internal structure including thermodynamics of magnesium sulfate oceans in contact with ice". Planetary and Space Science. 96: 62–70. Bibcode:2014P&SS...96...62V. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2014.03.011.

- ^ Staff (May 1, 2014). "Video (00:51) – Jupiter's 'Club Sandwich' Moon". NASA. Archived from the original on November 14, 2021. Retrieved May 2, 2014.

- ^ Kivelson, M.G.; Khurana, K.K.; et al. (2002). "The Permanent and Inductive Magnetic Moments of Ganymede" (PDF). Icarus. 157 (2): 507–522. Bibcode:2002Icar..157..507K. doi:10.1006/icar.2002.6834. hdl:2060/20020044825. S2CID 7482644. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 27, 2009. Retrieved January 15, 2008.

- ^ Eviatar, Aharon; Vasyliunas, Vytenis M.; et al. (2001). "The ionosphere of Ganymede" (ps). Planet. Space Sci. 49 (3–4): 327–336. Bibcode:2001P&SS...49..327E. doi:10.1016/S0032-0633(00)00154-9. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved January 16, 2008.

- ^ "Ganymede (satellite of Jupiter)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on June 18, 2019. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- ^ "Jupiter's Moons". The Planetary Society. Archived from the original on December 31, 2007.

- ^ "Satellites of Jupiter". The Galileo Project. Archived from the original on November 1, 2019. Retrieved November 24, 2007.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Pioneer 11was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "ESA Science & Technology – JUICE". ESA. November 8, 2021. Archived from the original on September 21, 2019. Retrieved November 10, 2021.

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (May 2, 2012). "Esa selects 1bn-euro Juice probe to Jupiter". BBC News. Archived from the original on May 11, 2020. Retrieved May 2, 2012.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).