Back Аевангелие Abkhazian Evangelie Afrikaans Evangelium (Buch) ALS ወንጌል Amharic Ata Etip ANN إنجيل Arabic ܐܘܢܓܠܝܘܢ ARC انجيل ARZ Evanxeliu AST İncil Azerbaijani

| Part of a series on |

| Books of the New Testament |

|---|

|

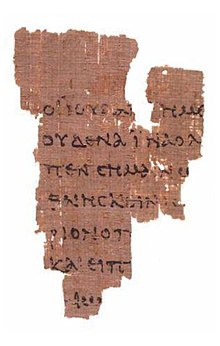

Gospel (‹See Tfd›Greek: εὐαγγέλιον; Latin: evangelium) originally meant the Christian message ("the gospel"), but in the 2nd century it came to be used also for the books in which the message was reported.[1] In this sense a gospel can be defined as a loose-knit, episodic narrative of the words and deeds of Jesus, culminating in his trial and death and concluding with various reports of his post-resurrection appearances.[2]

The gospels are a kind of bios, or ancient biography,[3] meant to convince people that Jesus was a charismatic miracle-working holy man, providing examples for readers to emulate.[4][5][6] As such, they present the Christian message of the second half of the first century AD,[7] and modern biblical scholars are cautious of relying on the gospels uncritically as historical documents, though they provide a good idea of Jesus's public career; according to Graham Stanton, with the potential exception of the Apostle Paul, we "know far more about Jesus of Nazareth than about any first or second century Jewish or pagan religious teacher".[8][note 1][9][10][note 2] [11] EP Sanders claimed that the sources for Jesus are superior to the ones for Alexander the Great. [12] Critical study on the Historical Jesus has largely failed to distinguish the original ideas of Jesus from those of the later Christian authors,[13][14] and the focus of research has shifted to Jesus as remembered by his followers,[15][16][note 3][note 4] and understanding the Gospels themselves.[17]

The canonical gospels are the four which appear in the New Testament of the Bible. They were probably written between AD 66 and 110,[18][19][20] which puts their composition likely within the lifetimes of various eyewitnesses, including Jesus's own family. [21] Most scholars hold that all four were anonymous (with the modern names of the "Four Evangelists" added in the 2nd century), almost certainly none were by eyewitnesses to the Historical Jesus, though most scholars view the author of Luke-Acts as an eyewitness to Paul, and all are the end-products of long oral and written transmission (which did involve eyewitnesses).[22][23][24][25][26][27] According to the majority of scholars, Mark was the first to be written, using a variety of sources,[28][29] followed by Matthew and Luke, which both independently used Mark for their narrative of Jesus's career, supplementing it with a collection of sayings called "the Q source", and additional material unique to each.[30] Alan Kirk praises Matthew in particular for his "scribal memory competence" and "his high esteem for and careful handling of both Mark and Q", which makes claims the latter two works are significantly theologically or historically different dubious. [31][32]There have been different views on the transmission of material that led to the Synoptic Gospels, with various scholars arguing memory or orality reliably preserved traditions that ultimately go back to the Historical Jesus.[33][34][35][36] Other scholars have been more skeptical and see more changes in the traditions prior to the written Gospels.[37][38] In modern scholarship, the Synoptic Gospels are the primary sources for reconstructing Christ's ministry while John is used less since it differs from the synoptics.[39][note 5] However, according to the manuscript evidence and citation frequency by the early Church Fathers, Matthew and John were the most popular Gospels while Luke and Mark were less popular in the early centuries of the church.[40]

Many non-canonical gospels were also written, all later than the four canonical gospels, and like them advocating the particular theological views of their various authors.[41][42] Important examples include the gospels of Thomas, Peter, Judas, and Mary; infancy gospels such as that of James (the first to introduce the perpetual virginity of Mary); and gospel harmonies such as the Diatessaron.

- ^ Cross & Livingstone 2005, p. 697.

- ^ Alexander 2006, p. 16.

- ^ Lincoln 2004, p. 133.

- ^ Ehrman 1999, p. 52.

- ^ Dunn 2005, p. 174.

- ^ Vermes 2013, p. 32.

- ^ Keith & Le Donne 2012, p. [page needed].

- ^ Sanders 1995b, p. 4-5.

- ^ Schoeps 1968, p. 261–262.

- ^ Ehrman 1999, p. 53.

- ^ Stanton, Graham (2002). The Gospels and Jesus (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 145. ISBN 978-0199246168

- ^ Sanders, EP (1996). The Historical Figure of Jesus. Penguin. p. 3. ISBN 0140144994.

- ^ Keith 2016.

- ^ Keith & Le Donne 2012.

- ^ Dunn 1995, pp. 371–372.

- ^ Dunn 2003.

- ^ Keith 2012.

- ^ Perkins 1998, p. 241.

- ^ Reddish 2011, pp. 108, 144.

- ^ Lincoln 2005, p. 18.

- ^ van Os, Bas (2011). Psychological Analyses and the Historical Jesus: New Ways to Explore Christian Origins. T&T Clark. p. 57, 83. ISBN 978-0567269515.

- ^ Reddish 2011, pp. 13, 42.

- ^ Simpson, Benjamin I. (1 April 2014). "review of The Historiographical Jesus. Memory, Typology, and the Son of David". The Voice. Dallas Theological Seminary.

- ^ Byrskog, Samuel (2000). Story as History - History as Story: The Gospel Tradition in the Context of Ancient Oral History. Mohr Siebrek Ek. p. 18-28, 69. ISBN 978-3161473050.

- ^ Keener, Craig (2015). Acts: An Exegetical Commentary (Volume 1). Baker Academic. p. 402. ISBN 978-0801039898.

- ^ Dunn, James (2016). The Acts of the Apostles. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. p. x. ISBN 978-0802874023.

- ^ Fitzmyer, Joseph (1998). The Acts of the Apostles (The Anchor Yale Bible Commentaries). Yale University Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-0300139822.

- ^ Goodacre 2001, p. 56.

- ^ Boring 2006, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Levine 2009, p. 6.

- ^ Kirk, Alan (2019). Q in Matthew: Ancient Media, Memory, and Early Scribal Transmission of the Jesus Tradition. T&T Clark. p. 298-306. ISBN 978-0567686541.

- ^ Rodriguez, Rafael (2017). "Matthew as Performer, Tradent, Scribe". Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus. 15 (2–3): 203. doi:10.1163/17455197-01502003.

- ^ Dunn 1995.

- ^ Wright, NT (1998). "Early Traditions and the Origins of Christianity". Sewanee Theological Review. 41 (2).

- ^ Bockmuehl, Markus (2006). Seeing the Word: Refocusing New Testament Study. Baker Academic. pp. 166–178. ISBN 978-0801027611.

- ^ McIver, Robert (2011). Memory, Jesus, and the Synoptic Gospels. Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1589835603.

- ^ Ehrman 1997.

- ^ Valantasis, Bleyle & Haugh 2009.

- ^ Sanders 2010.

- ^ Hill, Charles; Kruger, Michael (2012). "The Early Text of Matthew". The Early Text of the New Testament. Oxford University Press. p. 83. ISBN 9780199566365.

- ^ Petersen 2010, p. 51.

- ^ Culpepper 1999, p. 66.

Cite error: There are <ref group=note> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=note}} template (see the help page).