Back حقل جاذبية Arabic Qravitasiya sahəsi Azerbaijani Гравітацыйнае поле Byelorussian Гравитационно поле Bulgarian মহাকর্ষীয় ক্ষেত্র Bengali/Bangla Camp gravitatori Catalan Gravitační pole Czech Гравитаци уйĕ CV Tyngdefelt Danish Gravitationsfeld German

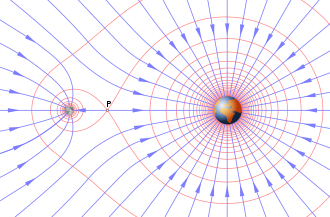

In physics, a gravitational field or gravitational acceleration field is a vector field used to explain the influences that a body extends into the space around itself.[1] A gravitational field is used to explain gravitational phenomena, such as the gravitational force field exerted on another massive body. It has dimension of acceleration (L/T2) and it is measured in units of newtons per kilogram (N/kg) or, equivalently, in meters per second squared (m/s2).

In its original concept, gravity was a force between point masses. Following Isaac Newton, Pierre-Simon Laplace attempted to model gravity as some kind of radiation field or fluid,[citation needed] and since the 19th century, explanations for gravity in classical mechanics have usually been taught in terms of a field model, rather than a point attraction. It results from the spatial gradient of the gravitational potential field.

In general relativity, rather than two particles attracting each other, the particles distort spacetime via their mass, and this distortion is what is perceived and measured as a "force".[citation needed] In such a model one states that matter moves in certain ways in response to the curvature of spacetime,[2] and that there is either no gravitational force,[3] or that gravity is a fictitious force.[4]

Gravity is distinguished from other forces by its obedience to the equivalence principle.

- ^ Feynman, Richard (1970). The Feynman Lectures on Physics. Vol. I. Addison Wesley Longman. ISBN 978-0-201-02115-8.

- ^ Geroch, Robert (1981). General Relativity from A to B. University of Chicago Press. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-226-28864-2.

- ^ Grøn, Øyvind; Hervik, Sigbjørn (2007). Einstein's General Theory of Relativity: with Modern Applications in Cosmology. Springer Japan. p. 256. ISBN 978-0-387-69199-2.

- ^ Foster, J.; Nightingale, J. D. (2006). A Short Course in General Relativity (3 ed.). Springer Science & Business. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-387-26078-5.