Back عبرنة أسماء الأماكن الفلسطينية Arabic Hebraización de topónimos palestinos Spanish Hebraisasi nama tempat Palestina ID Hebraizimi i emrave të vendeve palestineze Albanian 巴勒斯坦地名的希伯來化 Chinese

Hebrew-language names were coined for the place-names of Palestine throughout different periods under the British Mandate; after the establishment of Israel following the 1948 Palestinian expulsion and flight and 1948 Arab–Israeli War; and subsequently in the Palestinian territories occupied by Israel in 1967.[2][3] A 1992 study counted c. 2,780 historical locations whose names were Hebraized, including 340 villages and towns, 1,000 Khirbat (ruins), 560 wadis and rivers, 380 springs, 198 mountains and hills, 50 caves, 28 castles and palaces, and 14 pools and lakes.[4] Palestinians consider the Hebraization of place-names in Palestine part of the Palestinian Nakba.[5]

Many existing place names in Palestine are based on unknown etymologies. Some are descriptive, some survivals of ancient Nabataean, Hebrew Canaanite or other names, and the occasional name was unaltered from the forms found in the Hebrew Bible or Talmud.[6][7] During classical and late antiquity, the ancient place-names metamorphosed into Aramaic and Greek,[8][9] the two major languages spoken in the region before the advent of Islam.[9][8][10] Following the Muslim conquest of the Levant, Arabized forms of the ancient names were adopted.

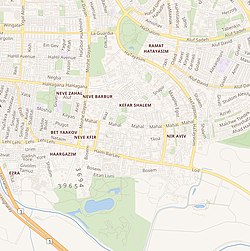

The Hebraization of place-names was encouraged by the Israeli government, aiming to strengthen the connection of Jews, most of whom had immigrated in recent decades, with the land.[11] As part of this process, many ancient Biblical or Talmudic place-names were "restored";[12] however, enthusiasm since cooled after mistakes were identified by archeologists.[13] In other cases, Hebraizations were chosen because the Hebrew was a homophone of the Arabic despite having a different meaning,[13] and sites with only Arabic names and no pre-existing ancient Hebrew names or associations were given new Hebrew names, thereby losing the historical tradition.[14][12] In some instances, the Palestinian Arabic place name was preserved in the modern Hebrew, despite there being a different Hebrew tradition regarding the name, as in the case of Banias, which in classical Hebrew writings is called Paneas.[15] Municipal direction sign-posts and maps produced by state-run agencies sometimes note the traditional Hebrew name and the traditional Arabic name alongside each other, such as "Nablus / Shechem" and "Silwan / Shiloach" etc.[16] In certain areas of Israel, particularly the mixed cities, there is a growing trend to restore the original Arabic street names that were Hebraized after 1948.[17][18]

- ^ Masalha, Nur (15 August 2018). Palestine: A Four Thousand Year History. Zed Books. ISBN 978-1-78699-275-8.

APPROPRIATION, HYBRIDISATION AND INDIGENISATION: THE APPROPRIATION OF PALESTINE PLACE NAMES BY EUROPEAN ZIONIST SETTLERS. From Palestinian Fuleh to Jewish Afula. The etymology of the Zionist settler toponym Afula is derived from the name of the Palestinian Arab village al‐Fuleh, which in 1226 Arab geographer Yaqut al‐Hamawi mentioned as being a town in the province of Jund Filastin. The Arabic toponym al‐Fuleh is derived from the word ful, for fava beans, which are among the oldest food plant in the Middle East and were widely cultivated by local Palestinians in Marj Ibn 'Amer.

- ^ Noga Kadman (7 September 2015). "Naming and Mapping the Depopulated Village Sites". Erased from Space and Consciousness: Israel and the Depopulated Palestinian Villages of 1948. Indiana University Press. pp. 91–. ISBN 978-0-253-01682-9.

- ^ Benvenisti 2000, p. 11.

- ^ Study by Palestinian geographer Shukri Arraf (1992), "The Palestinian locations between two eras/maps" (Arabic). Kufur Qari’: Matba’at, Al-Shuruq Al-Arabiya; quoted in Amara 2017, p. 106

- ^ Sa’di, Ahmad H. (2002). "Catastrophe, Memory and Identity: Al-Nakbah as a Component of Palestinian Identity". Israel Studies. 7 (2): 175–198. doi:10.2979/ISR.2002.7.2.175. JSTOR 30245590. S2CID 144811289.

, Al-Nakbah is associated with a rapid de-Arabization of the country. This process has included the destruction of Palestinian villages. About 418 villages were erased, and out of twelve Palestinian or mixed towns, a Palestinian population continued to exist in only seven. This swift transformation of the physical and cultural environment was accompanied, at the symbolic level, by the changing of the names of streets, neighborhoods, cities, and regions. Arabic names were replaced by Zionist, Jewish, or European names. This renaming continues to convey to the Palestinians the message that the country has seen only two historical periods which attest to its "true" nature: the ancient Jewish past, and the period that began with the creation of Israel.

- ^ Conder, C. R. (1881). Palmer, E. H. (ed.). "Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists". Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund: iv–v.

To determine the exact meaning of Arabic topographical names is by no means easy. Some are descriptive of physical features, but even these are often either obsolete or distorted words. Others are derived from long since forgotten incidents, or owners whose memory has passed away. Others again are survivals of older Nabathean, Hebrew, Canaanite, and other names, either quite meaningless in Arabic, or having an Arabic form in which the original sound is perhaps more or less preserved, but the sense entirely lost. Occasionally Hebrew, especially Biblical and Talmudic names, remain scarcely altered.

- ^ Rainey 1978, p. 7: “What surprised western scholars and explorers the most was the amazing degree to which biblical names were still preserved in the Arabic toponymy of Palestine”

- ^ a b Mila Neishtadt. 'The Lexical Substrate of Aramaic in Palestinian Arabic,' in Aaron Butts (ed.) Semitic Languages in Contact, BRILL 2015 pp.281-282:'As in other cases of language shift, the supplanting language (Arabic) was not left untouched by the supplanted language (Aramaic) and the existence of an Aramaic substrate in Syro-Palestinian colloquial Arabic has been widely accepted. The influence of the Aramaic substrate is especially evidence in many Palestinian place names, and in the vocabularies of traditional life and industrials: agriculture, flora, fauna, food, tools, utensils etc.'

- ^ a b Rainey 1978, p. 8: “In the majority of cases, a Greek or Latin name assigned by Hellenistic or Roman authorities enjoyed an existence only in official and literary circles while the Semitic- speaking populace continued to use the Hebrew or Aramaic original. The latter comes back into public use with the Arab conquest. The Arabic names Ludd, Beisan, and Saffurieh, representing original Lod, Bet Se’an and Sippori, leave no hint concerning their imposing Greco-Roman names, viz., Diospolis, Scythopolis, and Diocaesarea, respectively”

- ^ Nur Masalha, Palestine: A Four Thousand Year History, Zed Books 2018 ISBN 978-1-786-99275-8p.46:'Latin remained the official language of the government in the 6th century, whereas the prevalent language of merchants, farmers, seamen and ordinary citizens was Greek. Also, Aramaic -closely related to Arabic - was a prevalent language among the (predominantly Christian) Palestinian peasantry which constituted the majority of population in the country. Greek, however, became the lingua franca of late Byzantine Palestine, shortly before the advent of Islam. Consequently, the Hellenisation of Palestinian toponyms was not uncommon in Late Antiquity. A well known example of Hellenisation from Late Antiquity is the work of the 1st-century Romano-Jewish historian and translator Josephus who spoke Aramaic and Greek and who became a Roman citizen. Both he and Greco-Roman Jewish writer Philo of Alexandria used the toponym Palestine. He listed local Palestinian toponyms and rendered them familiar to Graeco-Roman audiences. Medieval Muslims and modern Palestinians preserved Greco-Roman toponyms such as Nablus (Greek: Neapolis/Νεάπολις), Palestine, Qaysariah (Caesarea/Καισάρεια), but not Philadelphia.'

- ^ Cohen, Saul B.; Kliot, Nurit (1992-12-01). "Place-Names in Israel's Ideological Struggle over the Administered Territories". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 82 (4): 653–680. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1992.tb01722.x. ISSN 0004-5608.

- ^ a b Miller and Hayes, 1986, p. 29.

- ^ a b Rainey 1978, p. 11: "Today there are Hebrew names not only for modern communities such as kibbutzim, settlement towns, etc., but for topographical features (hills, water sources, etc.), and antiquity sites as well. The majority of these are Hebraized forms of the former Arabic name, e.g., Arabic Tell 'Arâd is Tel ʿArad, Tell Jezer is now Tel Gezer, Khirbet Mešâš has become Tel Masos. Frequently, the new Hebrew form is not really cognate to the Arabic but was chosen for its general resemblance; Tell el-Fâr: "The Mound of the Mouse" has been promoted to Tel Par: "The Mound of the Bull." The earlier enthusiasm for restoring biblical names to their ancient sites has cooled down somewhat, especially after Tell (ʿArâq) el-Menšîyeh, changed to Tel Gat, was proved not to be a suitable candidate for Gath of the Philistines. Now the site is called Tel ʿErani after the epithet of Sheikh Ahmed el-ʿAreinī, whose tomb is located there."

- ^ Swedenburg, 2003, p. 50.

- ^ Vilnay, Zev (1954), p. 135 (section 9). Cf. Targum Shir HaShirim 5:4; etc. The reason for the hard-sounding "b" in the Arabic pronunciation of Banias has to do with the fact that, in the Arabic language, there is no hard "p" sound; the "p" being replaced by "b".

- ^ Sign welcoming visitors to Siloam (Shiloach), printed both in Hebrew and Arabic with traditional names, B'Tselem, 16 September 2014

- ^ Rekhess (2014). "The Arab Minority in Israel: Reconsidering the "1948 Paradigm"". Israel Studies. 19 (2): 187–217. doi:10.2979/israelstudies.19.2.187. JSTOR 10.2979/israelstudies.19.2.187. S2CID 144053751.

A new trend that has become particularly popular in recent years in mixed Jewish-Arab cities, is attempts to restore original Arabic street names, "Hebraized" after 1948

- ^ Ofer Aderet (29 July 2011). "A stir over sign language: A recently discovered trove of documents from the 1950s reveals a nasty battle in Jerusalem over the hebraization of street and neighborhood names. This campaign is still raging today". Haaretz. Retrieved 18 December 2011.