Back هنري مولاسون Arabic هنرى مولاسون ARZ Henry Molaison Czech Henry Molaison Danish Henry Gustav Molaison German Henry Molaison Spanish Henry Molaison Estonian HM (patient) French Henry Molaison Galician הנרי מולייסון HE

Henry Molaison | |

|---|---|

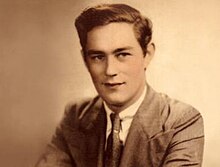

Molaison in 1953 before his surgery | |

| Born | Henry Gustav Molaison February 26, 1926 Manchester, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Died | December 2, 2008 (aged 82) |

Henry Gustav Molaison (February 26, 1926 – December 2, 2008), known widely as H.M., was an American who had a bilateral medial temporal lobectomy to surgically resect the anterior two thirds of his hippocampi, parahippocampal cortices, entorhinal cortices, piriform cortices, and amygdalae in an attempt to cure his epilepsy. Although the surgery was partially successful in controlling his epilepsy, a severe side effect was that he became unable to form new memories. His unique case also helped define ethical standards in neurological research, emphasizing the need for patient consent and the consideration of long-term impacts of medical interventions. Furthermore, Molaison's life after his surgery highlighted the challenges and adaptations required for living with significant memory impairments, serving as an important case study for healthcare professionals and caregivers dealing with similar conditions.

A childhood bicycle accident[note 1] is often advanced as the likely cause of H.M.'s epilepsy.[1] H.M. began to have minor seizures at age 10; from 16 years of age, the seizures became major. Despite high doses of anticonvulsant medication, H.M.'s seizures were incapacitating. When he was 27, H.M. was offered an experimental procedure by neurosurgeon W. B. Scoville. Previously Scoville had only ever performed the surgery on psychotic patients.

The surgery took place in 1953 and H.M. was widely studied from late 1957 until his death in 2008.[2][3] He resided in a care institute in Windsor Locks, Connecticut, where he was the subject of ongoing investigation.[4] His case played an important role in the development of theories that explain the link between brain function and memory, and in the development of cognitive neuropsychology, a branch of psychology that aims to understand how the structure and function of the brain relates to specific psychological processes.[5][6][7][8][9]

Molaison's brain was kept at University of California, San Diego, where it was sliced into histological sections on December 4, 2009.[10] It was later moved to the MIND Institute at UC Davis.[11] The brain atlas constructed was made publicly available in 2014.[12][13]

Cite error: There are <ref group=note> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=note}} template (see the help page).

- ^ Corkin, Suzanne (1984). "Lasting consequences of bilateral medial temporal lobectomy: Clinical course and experimental findings in H.M.". Seminars in Neurology. 4 (2). New York, NY: Thieme-Stratton Inc.: 249–259. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1041556. S2CID 71384121.

- ^ Benedict Carey (December 6, 2010). "No Memory, but He Filled In the Blanks". New York Times. Retrieved December 5, 2008.

- ^ Benedict Carey (December 4, 2008). "H. M., an Unforgettable Amnesiac, Dies at 82". New York Times. Retrieved December 5, 2008.

- ^ Schaffhausen, Joanna. "Henry Right Now". The Day His World Stood Still. BrainConnection.com. Archived from the original on February 9, 2008. Retrieved August 5, 2008.

- ^ Squire, Larry R. (January 2009). "The Legacy of Patient H.M. for Neuroscience". Neuron. 61 (1): 6–9. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2008.12.023. PMC 2649674. PMID 19146808.

- ^ Pattanayak, RamanDeep; Sagar, Rajesh; Shah, Bigya (2014). "The study of patient henry Molaison and what it taught us over past 50 years: Contributions to neuroscience". Journal of Mental Health and Human Behaviour. 19 (2): 91. doi:10.4103/0971-8990.153719. S2CID 143575922.

- ^ Dossani, Rimal Hanif; Missios, Symeon; Nanda, Anil (October 2015). "The Legacy of Henry Molaison (1926–2008) and the Impact of His Bilateral Mesial Temporal Lobe Surgery on the Study of Human Memory". World Neurosurgery. 84 (4): 1127–1135. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2015.04.031. PMID 25913428.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Levywas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Schacter, Daniel L. (2000). "Understanding implicit memory: A cognitive neuroscience approach". In Gazzaniga, M.S. (ed.). Cognitive Neuroscience: A Reader. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-631-21659-9.

- ^ Arielle Levin Becker (November 29, 2009). "Researchers To Study Pieces Of Unique Brain". The Hartford Courant. Archived from the original on January 6, 2010. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

- ^ Luke Dittrich (August 3, 2016). "The Brain That Couldn't Remember". The New York Times. Retrieved August 4, 2016.

- ^ Greg Miller (January 28, 2014). "Scientists Digitize Psychology's Most Famous Brain". Wired. Retrieved August 25, 2016.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

atlaswas invoked but never defined (see the help page).