Back Hindoestani Afrikaans Hindustani ALS Idioma hindostaní AN हिंदुस्तानी भाषा ANP اللغة الهندستانية Arabic Indostánicu AST Hindistani dili Azerbaijani هیندوستانی دیلی AZB Һиндостани Bashkir Basa Hindustani BAN

|

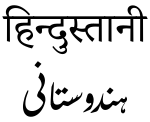

| Part of a series on the |

| Hindustani language |

|---|

| History |

| Grammar |

| Linguistic history |

| Accessibility |

Hindustani[d] is an Indo-Aryan language spoken in North India and Pakistan, and functioning as the lingua franca of the region.[12] It is also spoken by the Deccani people. Hindustani is a pluricentric language with two standard registers, known as Hindi (written in Devanagari script and influenced by Sanskrit) and Urdu (written in Perso-Arabic script and influenced by Persian and Arabic) which serve as official languages of India and Pakistan, respectively.[13][14] Thus, it is also called Hindi–Urdu.[15][16][17] Colloquial registers of the language fall on a spectrum between these standards.[18][19] In modern times, a third variety of Hindustani with significant English influences has also appeared, which is sometimes called Hinglish or Urdish.[20][21][22][23][24]

The concept of a Hindustani language as a "unifying language" or "fusion language" that could transcend communal and religious divisions across the subcontinent was endorsed by Mahatma Gandhi,[25] as it was not seen to be associated with either the Hindu or Muslim communities as was the case with Hindi and Urdu respectively, and it was also considered a simpler language for people to learn.[26][27] The conversion from Hindi to Urdu (or vice versa) is generally achieved by merely transliterating between the two scripts. Translation, on the other hand, is generally only required for religious and literary texts.[28]

Scholars trace the language's first written poetry, in the form of Old Hindi, to the Delhi Sultanate era around the twelfth and thirteenth century.[29][30][31] During the period of the Delhi Sultanate, which covered most of today's India, eastern Pakistan, southern Nepal and Bangladesh[32] and which resulted in the contact of Hindu and Muslim cultures, the Sanskrit and Prakrit base of Old Hindi became enriched with loanwords from Persian, evolving into the present form of Hindustani.[33][34][35][36][37][38][39] The Hindustani vernacular became an expression of Indian national unity during the Indian Independence movement,[40][41] and continues to be spoken as the common language of the people of the northern Indian subcontinent,[42] which is reflected in the Hindustani vocabulary of Bollywood films and songs.[43][44]

The language's core vocabulary is derived from Prakrit (a descendant of Sanskrit),[19][45][46][47][48] with substantial loanwords from Persian and Arabic (via Persian).[33][49][50][45][51] It is often written in the Devanagari script or the Arabic-derived Urdu script in the case of Hindi and Urdu respectively, with romanisation increasingly employed in modern times as a neutral script.[52][53]

As of 2023, Hindi and Urdu together constitute the 3rd-most-spoken language in the world after English and Mandarin, with 843 million native and second-language speakers, according to Ethnologue,[54] though this includes millions who self-reported their language as 'Hindi' on the Indian census but speak a number of other Hindi languages than Hindustani.[55] The total number of Hindi–Urdu speakers was reported to be over 300 million in 1995, making Hindustani the third- or fourth-most spoken language in the world.[56][45]

- ^ Robina Kausar; Muhammad Sarwar; Muhammad Shabbir (eds.). "The History of the Urdu Language Together with Its Origin and Geographic Distribution" (PDF). International Journal of Innovation and Research in Educational Sciences. 2 (1).

- ^ a b "Hindi" L1: 322 million (2011 Indian census), including perhaps 150 million speakers of other languages that reported their language as "Hindi" on the census. L2: 274 million (2016, source unknown). Urdu L1: 67 million (2011 & 2017 censuses), L2: 102 million (1999 Pakistan, source unknown, and 2001 Indian census): Ethnologue 21. Hindi at Ethnologue (21st ed., 2018)

. Urdu at Ethnologue (21st ed., 2018)

. Urdu at Ethnologue (21st ed., 2018)  .

.

- ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

Griersonwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c Ray, Aniruddha (2011). The Varied Facets of History: Essays in Honour of Aniruddha Ray. Primus Books. ISBN 978-93-80607-16-0.

There was the Hindustani Dictionary of Fallon published in 1879; and two years later (1881), John J. Platts produced his Dictionary of Urdu, Classical Hindi and English, which implied that Hindi and Urdu were literary forms of a single language. More recently, Christopher R. King in his One Language, Two Scripts (1994) has presented the late history of the single spoken language in two forms, with the clarity and detail that the subject deserves.

- ^ Gangopadhyay, Avik (2020). Glimpses of Indian Languages. Evincepub publishing. p. 43. ISBN 9789390197828.

- ^ Norms & Guidelines Archived 13 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine, 2009. D.Ed. Special Education (Deaf & Hard of Hearing), [www.rehabcouncil.nic.in Rehabilitation Council of India]

- ^ The Central Hindi Directorate regulates the use of Devanagari and Hindi spelling in India. Source: Central Hindi Directorate: Introduction Archived 15 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "National Council for Promotion of Urdu Language". www.urducouncil.nic.in.

- ^ Zia, K. (1999). Standard Code Table for Urdu Archived 8 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine. 4th Symposium on Multilingual Information Processing, (MLIT-4), Yangon, Myanmar. CICC, Japan. Retrieved on 28 May 2008.

- ^

- McGregor, R. S., ed. (1993), "हिंदुस्तानी", The Oxford Hindi-English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, p. 1071,

2. hindustani [P. hindustani] f Hindustani (a mixed Hindi dialect of the Delhi region which came to be used as a lingua franca widely throughout India and what is now Pakistan)

- "हिंदुस्तानी", बृहत हिंदी कोश खंड 2 (Large Hindi Dictionary, Volume 2), केन्द्रीय हिंदी निदेशालय, भारत सरकार (Central Hindi Directorate, Government of India), p. 1458, retrieved 17 October 2021

- Das, Shyamasundar (1975), Hindi Shabda Sagar (Hindi dictionary) in 11 volumes, revised edition, Kashi (Varanasi): Nagari Pracharini Sabha, p. 5505,

हिंदुस्तानी hindustānī३ संज्ञा स्त्री॰ १. हिंदुस्तान की भाषा । २. बोलचाल या व्यवहार की वह हिंदी जिसमें न तो बहुत अरबी फारसी के शब्द हों न संस्कृत के । उ॰—साहिब लोगों ने इस देश की भाषा का एक नया नाम हिंदुस्तानी रखा । Translation: Hindustani hindustānī3 noun feminine 1. The language of Hindustan. 2. That version of Hindi employed for common speech or business in which neither many Arabic or Persian words nor Sanskrit words are present. Context: The British gave the new name Hindustani to the language of this country.

- Chaturvedi, Mahendra (1970), "हिंदुस्तानी", A Practical Hindi-English Dictionary, Delhi: National Publishing House,

hindustānī hīndusta:nī: a theoretically existent style of the Hindi language which is supposed to consist of current and simple words of any sources whatever and is neither too much biassed in favour of Perso-Arabic elements nor has any place for too much high-flown Sanskritized vocabulary

- McGregor, R. S., ed. (1993), "हिंदुस्तानी", The Oxford Hindi-English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, p. 1071,

- ^ "About Hindi-Urdu". North Carolina State University. Archived from the original on 15 August 2009. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

siddiqi1994was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Hindustani language". Encyclopedia Britannica. 1 November 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

(subscription required) lingua franca of northern India and Pakistan. Two variants of Hindustani, Urdu and Hindi, are official languages in Pakistan and India, respectively. Hindustani began to develop during the 13th century CE in and around the Indian cities of Delhi and Meerut in response to the increasing linguistic diversity that resulted from Muslim hegemony. In the 19th century its use was widely promoted by the British, who initiated an effort at standardization. Hindustani is widely recognized as India's most common lingua franca, but its status as a vernacular renders it difficult to measure precisely its number of speakers.

- ^ Yoon, Bogum; Pratt, Kristen L., eds. (15 January 2023). Primary Language Impact on Second Language and Literacy Learning. Lexington Books. p. 198.

In terms of cross-linguistic relations, Urdu's combinations of Arabic-Persian orthography and Sanskrit linguistic roots provides interesting theoretical as well as practical comparisons demonstrated in table 12.1.

- ^ Trask, R. L. (8 August 2019), "Hindi-Urdu", Dictionary of Historical and Comparative Linguistics, Edinburgh University Press, pp. 149–150, ISBN 9781474473316,

Hindi-Urdu The most important modern Indo-Aryan language, spoken by well over 250 million people, mainly in India and Pakistan. At the spoken level Hindi and Urdu are the same language (called Hindustani before the political partition), but the two varieties are written in different alphabets and differ substantially in their abstract and technical vocabularies

- ^ Crystal, David (2001), A Dictionary of Language, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 9780226122038,

(p. 115) Figure: A family of languages: the Indo-European family tree, reflecting geographical distribution. Proto Indo-European>Indo-Iranian>Indo-Aryan (Sanskrit)> Midland (Rajasthani, Bihari, Hindi/Urdu); (p. 149) Hindi There is little structural difference between Hindi and Urdu, and the two are often grouped together under the single label Hindi/Urdu, sometimes abbreviated to Hirdu, and formerly often called Hindustani; (p. 160) India ... With such linguistic diversity, Hindi/Urdu has come to be widely used as a lingua franca.

- ^ Gandhi, M. K. (2018). An Autobiography or The Story of My Experiments with Truth: A Critical Edition. Translated by Desai, Mahadev. annotation by Suhrud, Tridip. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300234077.

(p. 737) I was handicapped for want of suitable Hindi or Urdu words. This was my first occasion for delivering an argumentative speech before an audience especially composed of Mussalmans of the North. I had spoken in Urdu at the Muslim League at Calcutta, but it was only for a few minutes, and the speech was intended only to be a feeling appeal to the audience. Here, on the contrary, I was faced with a critical, if not hostile, audience, to whom I had to explain and bring home my view-point. But I had cast aside all shyness. I was not there to deliver an address in the faultless, polished Urdu of the Delhi Muslims, but to place before the gathering my views in such broken Hindi as I could command. And in this I was successful. This meeting afforded me a direct proof of the fact that Hindi-Urdu alone could become the lingua franca<Footnote M8> of India. (M8: "national language" in the Gujarati original).

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Basu2017was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Gube, Jan; Gao, Fang (2019). Education, Ethnicity and Equity in the Multilingual Asian Context. Springer Publishing. ISBN 978-981-13-3125-1.

The national language of India and Pakistan 'Standard Urdu' is mutually intelligible with 'Standard Hindi' because both languages share the same Indic base and are all but indistinguishable in phonology and grammar (Lust et al. 2000).

- ^ Kothari, Rita; Snell, Rupert (2011). Chutnefying English: The Phenomenon of Hinglish. Penguin Books India. ISBN 978-0-14-341639-5.

- ^ "Hindi, Hinglish: Head to Head". read.dukeupress.edu. Retrieved 29 October 2023.

- ^ Salwathura, A. N. "Evolutionary development of ‘hinglish’language within the indian sub-continent." International Journal of Research-GRANTHAALAYAH. Vol. 8. No. 11. Granthaalayah Publications and Printers, 2020. 41-48.

- ^ Vanita, Ruth (1 April 2009). "Eloquent Parrots; Mixed Language and the Examples of Hinglish and Rekhti". International Institute for Asian Studies Newsletter (50): 16–17.

- ^ Singh, Rajendra (1 January 1985). "Modern Hindustani and Formal and Social Aspects of Language Contact". ITL - International Journal of Applied Linguistics. 70 (1): 33–60. doi:10.1075/itl.70.02sin. ISSN 0019-0829.

- ^ "After experiments with Hindi as national language, how Gandhi changed his mind". Prabhu Mallikarjunan. The Feral. 3 October 2019.

- ^ Rai, Alok. "The Persistence of Hindustani". ResearchGate.

- ^ Lelyveld, David (1 January 1993). "Colonial knowledge and the fate of Hindustani". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 35 (4): 665–682. doi:10.1017/S0010417500018661. S2CID 144180838.

- ^ Bhat, Riyaz Ahmad; Bhat, Irshad Ahmad; Jain, Naman; Sharma, Dipti Misra (2016). "A House United: Bridging the Script and Lexical Barrier between Hindi and Urdu" (PDF). Proceedings of COLING 2016, the 26th International Conference on Computational Linguistics. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

Hindi and Urdu transliteration has received a lot of attention from the NLP research community of South Asia (Malik et al., 2008; Lehal and Saini, 2012; Lehal and Saini, 2014). It has been seen to break the barrier that makes the two look different.

- ^ Dhanesh Jain; George Cardona, eds. (2007). The Indo-Aryan languages. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-79711-9. OCLC 648298147.

Such an early date for the inception of a Hindi literature, one made possible only by subsuming the large body of Apabhraṁśa literature into Hindi, has not, however, been generally accepted by scholars (p. 279).

- ^ Kachru, Yamuna (2006). Hindi. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing.

The period between 1000 AD-1200/1300 AD is designated the Old NIA stage because it is at this stage that the NIA languages such as Assamese, Bengali, Gujarati, Hindi, Marathi, Oriya, Punjabi assumed distinct identities (p. 1, emphasis added)

- ^ Dua, Hans (2008). "Hindustani". In Keith Brown; Sarah Ogilvie (eds.). Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World. Oxford: Elsevier. pp. 497–500.

Hindustani as a colloquial speech developed over almost seven centuries from 1100 to 1800 (p. 497, emphasis added).

- ^ Chapman, Graham. "Religious vs. regional determinism: India, Pakistan and Bangladesh as inheritors of empire." Shared space: Divided space. Essays on conflict and territorial organization (1990): 106-134.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Brill1993was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Women of the Indian Sub-Continent: Makings of a Culture - Rekhta Foundation". Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

The "Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb" is one such instance of the composite culture that marks various regions of the country. Prevalent in the North, particularly in the central plains, it is born of the union between the Hindu and Muslim cultures. Most of the temples were lined along the Ganges and the Khanqah (Sufi school of thought) were situated along the Yamuna river (also called Jamuna). Thus, it came to be known as the Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb, with the word "tehzeeb" meaning culture. More than communal harmony, its most beautiful by-product was "Hindustani" which later gave us the Hindi and Urdu languages.

- ^ Matthews, David John; Shackle, C.; Husain, Shahanara (1985). Urdu literature. Urdu Markaz; Third World Foundation for Social and Economic Studies. ISBN 978-0-907962-30-4.

But with the establishment of Muslim rule in Delhi, it was the Old Hindi of this area which came to form the major partner with Persian. This variety of Hindi is called Khari Boli, 'the upright speech'.

- ^ Dhulipala, Venkat (2000). The Politics of Secularism: Medieval Indian Historiography and the Sufis. University of Wisconsin–Madison. p. 27.

Persian became the court language, and many Persian words crept into popular usage. The composite culture of northern India, known as the Ganga Jamuni tehzeeb was a product of the interaction between Hindu society and Islam.

- ^ Indian Journal of Social Work, Volume 4. Tata Institute of Social Sciences. 1943. p. 264.

... more words of Sanskrit origin but 75% of the vocabulary is common. It is also admitted that while this language is known as Hindustani, ... Muslims call it Urdu and the Hindus call it Hindi. ... Urdu is a national language evolved through years of Hindu and Muslim cultural contact and, as stated by Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, is essentially an Indian language and has no place outside.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Mody2008was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Kesavan, B. S. (1997). History Of Printing And Publishing In India. National Book Trust, India. p. 31. ISBN 978-81-237-2120-0.

It might be useful to recall here that Old Hindi or Hindavi, which was a naturally Persian- mixed language in the largest measure, has played this role before, as we have seen, for five or six centuries.

- ^ Hans Henrich Hock (1991). Principles of Historical Linguistics. Walter de Gruyter. p. 475. ISBN 978-3-11-012962-5.

During the time of British rule, Hindi (in its religiously neutral, 'Hindustani' variety) increasingly came to be the symbol of national unity over against the English of the foreign oppressor. And Hindustani was learned widely throughout India, even in Bengal and the Dravidian south. ... Independence had been accompanied by the division of former British India into two countries, Pakistan and India. The former had been established as a Muslim state and had made Urdu, the Muslim variety of Hindi–Urdu or Hindustani, its national language.

- ^ Masica, Colin P. (1993). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Cambridge University Press. pp. 430 (Appendix I). ISBN 978-0-521-29944-2.

Hindustani - term referring to common colloquial base of HINDI and URDU and to its function as lingua franca over much of India, much in vogue during Independence movement as expression of national unity; after Partition in 1947 and subsequent linguistic polarization it fell into disfavor; census of 1951 registered an enormous decline (86-98 per cent) in no. of persons declaring it their mother tongue (the majority of HINDI speakers and many URDU speakers had done so in previous censuses); trend continued in subsequent censuses: only 11,053 returned it in 1971...mostly from S India; [see Khubchandani 1983: 90-1].

- ^ Ashmore, Harry S. (1961). Encyclopaedia Britannica: a new survey of universal knowledge, Volume 11. Encyclopædia Britannica. p. 579.

The everyday speech of well over 50,000,000 persons of all communities in the north of India and in West Pakistan is the expression of a common language, Hindustani.

- ^ Tunstall, Jeremy (2008). The media were American: U.S. mass media in decline. Oxford University Press. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-19-518146-3.

The Hindi film industry used the most popular street level version of Hindi, namely Hindustani, which included a lot of Urdu and Persian words.

- ^ Hiro, Dilip (2015). The Longest August: The Unflinching Rivalry Between India and Pakistan. PublicAffairs. p. 398. ISBN 978-1-56858-503-1.

Spoken Hindi is akin to spoken Urdu, and that language is often called Hindustani. Bollywood's screenplays are written in Hindustani.

- ^ a b c Delacy, Richard; Ahmed, Shahara (2005). Hindi, Urdu & Bengali. Lonely Planet. pp. 11–12.

Hindi and Urdu are generally considered to be one spoken language with two different literary traditions. That means that Hindi and Urdu speakers who shop in the same markets (and watch the same Bollywood films) have no problems understanding each other.

- ^ "Ties between Urdu & Sanskrit deeply rooted: Scholar". The Times of India. 12 March 2024. Retrieved 8 May 2024.

The linguistic and cultural ties between Sanskrit and Urdu are deeply rooted and significant, said Ishtiaque Ahmed, registrar, Maula Azad National Urdu University during a two-day workshop titled "Introduction to Sanskrit for Urdu medium students". Ahmed said a substantial portion of Urdu's vocabulary and cultural capital, as well as its syntactic structure, is derived from Sanskrit.

- ^ Kuiper, Kathleen (2010). The Culture of India. Rosen Publishing. ISBN 978-1-61530-149-2.

Urdu is closely related to Hindi, a language that originated and developed in the Indian subcontinent. They share the same Indic base and are so similar in phonology and grammar that they appear to be one language.

- ^ Chatterji, Suniti Kumar; Siṃha, Udaẏa Nārāẏana; Padikkal, Shivarama (1997). Suniti Kumar Chatterji: a centenary tribute. Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 978-81-260-0353-2.

High Hindi written in Devanagari, having identical grammar with Urdu, employing the native Hindi or Hindustani (Prakrit) elements to the fullest, but for words of high culture, going to Sanskrit. Hindustani proper that represents the basic Khari Boli with vocabulary holding a balance between Urdu and High Hindi.

- ^ Draper, Allison Stark (2003). India: A Primary Source Cultural Guide. Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8239-3838-4.

People in Delhi spoke Khari Boli, a language the British called Hindustani. It used an Indo-Aryan grammatical structure and numerous Persian "loan-words."

- ^ Ahmad, Aijaz (2002). Lineages of the Present: Ideology and Politics in Contemporary South Asia. Verso. p. 113. ISBN 9781859843581.

On this there are far more reliable statistics than those on population. Farhang-e-Asafiya is by general agreement the most reliable Urdu dictionary. It twas compiled in the late nineteenth century by an Indian scholar little exposed to British or Orientalist scholarship. The lexicographer in question, Syed Ahmed Dehlavi, had no desire to sunder Urdu's relationship with Farsi, as is evident even from the title of his dictionary. He estimates that roughly 75 per cent of the total stock of 55,000 Urdu words that he compiled in his dictionary are derived from Sanskrit and Prakrit, and that the entire stock of the base words of the language, without exception, are derived from these sources. What distinguishes Urdu from a great many other Indian languauges ... is that is draws almost a quarter of its vocabulary from language communities to the west of India, such as Farsi, Turkish, and Tajik. Most of the little it takes from Arabic has not come directly but through Farsi.

- ^ Dalmia, Vasudha (31 July 2017). Hindu Pasts: Women, Religion, Histories. SUNY Press. p. 310. ISBN 9781438468075.

On the issue of vocabulary, Ahmad goes on to cite Syed Ahmad Dehlavi as he set about to compile the Farhang-e-Asafiya, an Urdu dictionary, in the late nineteenth century. Syed Ahmad 'had no desire to sunder Urdu's relationship with Farsi, as is evident from the title of his dictionary. He estimates that roughly 75 per cent of the total stock of 55.000 Urdu words that he compiled in his dictionary are derived from Sanskrit and Prakrit, and that the entire stock of the base words of the language, without exception, are from these sources' (2000: 112-13). As Ahmad points out, Syed Ahmad, as a member of Delhi's aristocratic elite, had a clear bias towards Persian and Arabic. His estimate of the percentage of Prakitic words in Urdu should therefore be considered more conservative than not. The actual proportion of Prakitic words in everyday language would clearly be much higher.

- ^ Brandt, Carmen; Sohoni, Pushkar (2 January 2018). "Script and identity – the politics of writing in South Asia: an introduction". South Asian History and Culture. 9 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1080/19472498.2017.1411048. ISSN 1947-2498. S2CID 148802248.

- ^ Brandt, Carmen (1 January 2020). "From a Symbol of Colonial Conquest to the Scripta Franca: The Roman Script for South Asian Languages". Academia.

- ^ Not considering whether speakers may be bilingual in Hindi and Urdu. "What are the top 200 most spoken languages?". Ethnologue. 2023. Retrieved 11 August 2024.

- ^ "Scheduled Languages in descending order of speaker's strength - 2011" (PDF). Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India. 29 June 2018.

- ^ Gambhir, Vijay (1995). The Teaching and Acquisition of South Asian Languages. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-3328-5.

The position of Hindi–Urdu among the languages of the world is anomalous. The number of its proficient speakers, over three hundred million, places it in third of fourth place after Mandarin, English, and perhaps Spanish.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).