Back Hipnose Afrikaans Oferswefn ANG تنويم مغناطيسي Arabic ايحاء ARZ Hipnosis AST Hipnoz Azerbaijani هیپنوتیسم AZB Гіпноз Byelorussian Гіпноз BE-X-OLD Хипноза Bulgarian

| Hypnosis | |

|---|---|

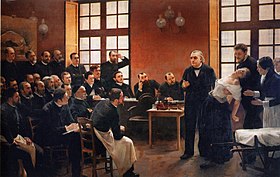

Jean-Martin Charcot demonstrating hypnosis on a "hysterical" Salpêtrière patient, "Blanche" (Marie Wittman), who is supported by Joseph Babiński[1] | |

| MeSH | D006990 |

| Hypnosis |

|---|

Hypnosis is a human condition involving focused attention (the selective attention/selective inattention hypothesis, SASI),[2] reduced peripheral awareness, and an enhanced capacity to respond to suggestion.[3]

There are competing theories explaining hypnosis and related phenomena. Altered state theories see hypnosis as an altered state of mind or trance, marked by a level of awareness different from the ordinary state of consciousness.[4][5] In contrast, non-state theories see hypnosis as, variously, a type of placebo effect,[6][7] a redefinition of an interaction with a therapist[8] or a form of imaginative role enactment.[9][10][11]

During hypnosis, a person is said to have heightened focus and concentration[12][13] and an increased response to suggestions.[14] Hypnosis usually begins with a hypnotic induction involving a series of preliminary instructions and suggestions. The use of hypnosis for therapeutic purposes is referred to as "hypnotherapy",[15] while its use as a form of entertainment for an audience is known as "stage hypnosis", a form of mentalism.

Hypnosis-based therapies for the management of irritable bowel syndrome and menopause are supported by evidence.[16][17] The use of hypnosis as a form of therapy to retrieve and integrate early trauma is controversial within the scientific mainstream. Research indicates that hypnotising an individual may aid the formation of false memories,[18][19] and that hypnosis "does not help people recall events more accurately".[20] Medical hypnosis is often considered pseudoscience or quackery.[21]

- ^ See: A Clinical Lesson at the Salpêtrière.

- ^ Hall, Harriet (2021). "Hypnosis revisited". Skeptical Inquirer. 45 (2): 17–19.

- ^ In 2015, the American Psychological Association Division 30 defined hypnosis as a "state of consciousness involving focused attention and reduced peripheral awareness characterized by an enhanced capacity for response to suggestion". For critical commentary on this definition, see: Lynn SJ, Green JP, Kirsch I, Capafons A, Lilienfeld SO, Laurence JR, Montgomery GH (April 2015). "Grounding Hypnosis in Science: The "New" APA Division 30 Definition of Hypnosis as a Step Backward". The American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis. 57 (4): 390–401. doi:10.1080/00029157.2015.1011472. PMID 25928778. S2CID 10797114.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, 2004: "a special psychological state with certain physiological attributes, resembling sleep only superficially and marked by a functioning of the individual at a level of awareness other than the ordinary conscious state".

- ^ Erika Fromm; Ronald E. Shor (2009). Hypnosis: Developments in Research and New Perspectives. Rutgers. ISBN 978-0-202-36262-5. Archived from the original on 2 July 2023. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^ Kirsch I (October 1994). "Clinical hypnosis as a nondeceptive placebo: empirically derived techniques". The American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis. 37 (2): 95–106. doi:10.1080/00029157.1994.10403122. PMID 7992808.

- ^ Kirsch, I., "Clinical Hypnosis as a Nondeceptive Placebo", pp. 211–25 in Kirsch, I., Capafons, A., Cardeña-Buelna, E., Amigó, S. (eds.), Clinical Hypnosis and Self-Regulation: Cognitive-Behavioral Perspectives, American Psychological Association, (Washington), 1999 ISBN 1-55798-535-9

- ^ Theodore X. Barber (1969). Hypnosis: A Scientific Approach. J. Aronson, 1995. ISBN 978-1-56821-740-6.

- ^ Lynn S, Fassler O, Knox J (2005). "Hypnosis and the altered state debate: something more or nothing more?". Contemporary Hypnosis. 22: 39–45. doi:10.1002/ch.21.

- ^ Coe WC, Buckner LG, Howard ML, Kobayashi K (July 1972). "Hypnosis as role enactment: focus on a role specific skill". The American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis. 15 (1): 41–45. doi:10.1080/00029157.1972.10402209. PMID 4679790.

- ^ Steven J. Lynn; Judith W. Rhue (1991). Theories of hypnosis: current models and perspectives. Guilford Press. ISBN 978-0-89862-343-7. Archived from the original on 2 July 2023. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ^ Orne, M. T. (1962). On the social psychology of the psychological experiment: With particular reference to demand characteristics and their implications. American Psychologist, 17, 776-783

- ^ Segi, Sherril (2012). "Hypnosis for pain management, anxiety and behavioral disorders". The Clinical Advisor: For Nurse Practitioners. 15 (3): 80. ISSN 1524-7317.

- ^ Lyda, Alex. "Hypnosis Gaining Ground in Medicine." Columbia News Archived 7 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Columbia.edu. Retrieved on 1 October 2011.

- ^ Spanos, N. P., Spillane, J., & McPeake, J. D. (1976). Cognitive strategies and response to suggestion in hypnotic and task-motivated subjects. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 18, 252-262.

- ^ Lacy, Brian E.; Pimentel, Mark; Brenner, Darren M.; Chey, William D.; Keefer, Laurie A.; Long, Millie D.; Moshiree, Baha (January 2021). "ACG Clinical Guideline: Management of Irritable Bowel Syndrome". American Journal of Gastroenterology. 116 (1): 17–44. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000001036. ISSN 0002-9270. PMID 33315591.

- ^ "Nonhormonal management of menopause-associated vasomotor symptoms: 2015 position statement of The North American Menopause Society". Menopause. 22 (11): 1155–1172, quiz 1173–1174. November 2015. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000546. ISSN 1530-0374. PMID 26382310. S2CID 14841660. Archived from the original on 22 March 2021. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ Lynn, Steven Jay; Krackow, Elisa; Loftus, Elizabeth F.; Locke, Timothy G.; Lilienfeld, Scott O. (2014). "Constructing the past: problematic memory recovery techniques in psychotherapy". In Lilienfeld, Scott O.; Lynn, Steven Jay; Lohr, Jeffrey M. (eds.). Science and pseudoscience in clinical psychology (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press. pp. 245–275. ISBN 9781462517510. OCLC 890851087.

- ^ French, Christopher C. (2023). "Hypnotic Regression and False Memories". In Ballester-Olmos, V.J.; Heiden, Richard W. (eds.). The Reliability of UFO Witness Testimony. Turin, Italy: UPIAR. pp. 283–294. ISBN 9791281441002.

- ^ Hall, Celia (26 August 2001). "Hypnosis does not help accurate memory recall, says study". Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

naudwas invoked but never defined (see the help page).