Back استنفاد فضاء عناوين الإصدار الرابع من بروتوكول الإنترنت Arabic Вычарпанне IPv4-адрасоў Byelorussian Vyčerpání IPv4 adres Czech IPv6#Gründe für ein neues Internet-Protokoll German Εξάντληση διευθύνσεων IPv4 Greek Agotamiento de las direcciones IPv4 Spanish فرسودگی آی پی نسخه چهار Persian Épuisement des adresses IPv4 French Az IPv4-címek elfogyása Hungarian IPv4 հասցեի սպառում Armenian

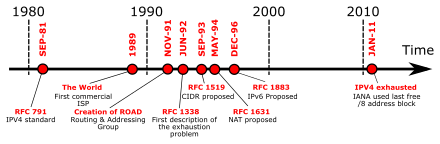

IPv4 address exhaustion is the depletion of the pool of unallocated IPv4 addresses. Because the original Internet architecture had fewer than 4.3 billion addresses available, depletion has been anticipated since the late 1980s when the Internet started experiencing dramatic growth. This depletion is one of the reasons for the development and deployment of its successor protocol, IPv6.[1] IPv4 and IPv6 coexist on the Internet.

The IP address space is managed globally by the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA), and by five regional Internet registries (RIRs) responsible in their designated territories for assignment to end users and local Internet registries, such as Internet service providers. The main market forces that accelerated IPv4 address depletion included the rapidly growing number of Internet users, always-on devices, and mobile devices.

The anticipated shortage has been the driving factor in creating and adopting several new technologies, including network address translation (NAT), Classless Inter-Domain Routing (CIDR) in 1993, and IPv6 in 1998.[2]

The top-level exhaustion occurred on 31 January 2011.[3][4][5][6] All RIRs have exhausted their address pools, except those reserved for IPv6 transition; this occurred on 15 April 2011 for the Asia-Pacific (APNIC),[7][8][9] on 10 June 2014 for Latin America and the Caribbean (LACNIC),[10] on 24 September 2015 for North America (ARIN),[11] on 21 April 2017 for Africa (AfriNIC),[12] and on 25 November 2019 for Europe, Middle East and Central Asia (RIPE NCC).[13] These RIRs still allocate recovered addresses or addresses reserved for a special purpose. Individual ISPs still have pools of unassigned IP addresses, and could recycle addresses no longer needed by subscribers.

Vint Cerf co-created TCP/IP thinking it was an experiment and has admitted he thought 32 bits was enough.[14][15][16][17]

- ^ Li, Kwun-Hung; Wong, Kin-Yeung (14 June 2021). "Empirical Analysis of IPv4 and IPv6 Networks through Dual-Stack Sites". Information. 12 (6): 246. doi:10.3390/info12060246. ISSN 2078-2489.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Murphywas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Smith, Lucie; Lipner, Ian (3 February 2011). "Free Pool of IPv4 Address Space Depleted". Number Resource Organization. Archived from the original on 13 August 2011. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- ^ "Available Pool of Unallocated IPv4 Internet Addresses Now Completely Emptied" (PDF). ICANN. 3 February 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 August 2011. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ^ "Major Announcement Set on Dwindling Pool of Available IPv4 Internet Addresses" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 March 2011. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ^ ICANN, nanog mailing list. "Five /8s allocated to RIRs – no unallocated IPv4 unicast /8s remain". Archived from the original on 27 August 2011. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- ^ Huston, Geoff. "IPv4 Address Report, daily generated". Archived from the original on 6 August 2011. Retrieved 16 January 2011.

- ^ "Two /8s allocated to APNIC from IANA". APNIC. 1 February 2010. Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- ^ "APNIC IPv4 Address Pool Reaches Final /8". APNIC. 15 April 2011. Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ^ "LACNIC Enters IPv4 Exhaustion Phase - The Number Resource Organization". Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ^ "ARIN IPv4 Free Pool Reaches Zero". American Registry for Internet Numbers. 24 September 2015. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- ^ "IPv4 Exhaustion - AFRINIC". Regional Internet Registry for Africa. 17 January 2020. Archived from the original on 15 September 2020. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- ^ "The RIPE NCC has run out of IPv4 Addresses". Réseaux IP Européens Network Coordination Centre. 25 November 2019. Archived from the original on 25 November 2019. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- ^ Perry, Tekla (7 May 2023). "Vint Cerf on 3 Mistakes He Made in TCP/IP". IEEE Spectrum. Archived from the original on 8 May 2023. Retrieved 8 May 2023.

- ^ Moses, Asher; Grubb, Ben (21 January 2011). "Internet Armageddon all my fault: Google chief". Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 3 February 2023. Retrieved 8 May 2023.

- ^ Trout, Christopher (26 January 2011). "Vint Cerf on IPv4 depletion: 'Who the hell knew how much address space we needed?'". Engadget. Archived from the original on 3 February 2023. Retrieved 8 May 2023.

- ^ "Google IPv6 Conference 2008: What will the IPv6 Internet look like?". Google TechTalks channel on YouTube. 29 January 2008. Cerf quote starts 13½ minutes into the video.

I'm serious, the decision to put a 32-bit address space on there was the result of a year's battle among a bunch of engineers who couldn't make up their minds about 32, 128 or variable length. And after a year of fighting I said - I'm now at ARPA, I'm running the program, I'm paying for this stuff and using American tax dollars - and I wanted some progress because we didn't know if this is going to work. So I said - 32 bits, it is enough for an experiment, it is 4.3 billion terminations - even the defense department doesn't need 4.3 billion of anything and it couldn't afford to buy 4.3 billion edge devices to do a test anyway. So at the time I thought we were doing a experiment to prove the technology and that if it worked we'd have an opportunity to do a production version of it. Well - it just escaped! - it got out and people started to use it and then it became a commercial thing. So, this [IPv6] is the production attempt at making the network scalable. Only 30 years later.