Back Аисланд бызшәа Abkhazian Yslands Afrikaans Isländische Sprache ALS አይስላንድኛ Amharic Idioma islandés AN Īslendisc sprǣc ANG आइसलैंडिक भाषा ANP اللغة الآيسلندية Arabic ايسلاندى ARZ Idioma islandés AST

| Icelandic | |

|---|---|

| íslenska | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈistlɛnska] |

| Native to | Iceland |

| Ethnicity | Icelanders |

Native speakers | (undated figure of 330,000)[1] |

Indo-European

| |

Early forms | |

| Latin (Icelandic alphabet) Icelandic Braille | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Regulated by | Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies[a] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | is |

| ISO 639-2 | ice (B) isl (T) |

| ISO 639-3 | isl |

| Glottolog | icel1247 |

| Linguasphere | 52-AAA-aa |

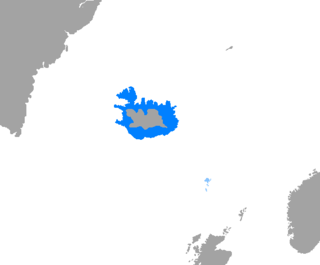

Geographic distribution of the Icelandic language | |

Icelandic (/aɪsˈlændɪk/ eyess-LAN-dik; endonym: íslenska, pronounced [ˈistlɛnska] ) is a North Germanic language from the Indo-European language family spoken by about 314,000 people, the vast majority of whom live in Iceland, where it is the national language.[2] Since it is a West Scandinavian language, it is most closely related to Faroese, western Norwegian dialects, and the extinct language Norn. It is not mutually intelligible with the continental Scandinavian languages (Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish) and is more distinct from the most widely spoken Germanic languages, English and German. The written forms of Icelandic and Faroese are very similar, but their spoken forms are not mutually intelligible.[3]

The language is more conservative than most other Germanic languages. While most of them have greatly reduced levels of inflection (particularly noun declension), Icelandic retains a four-case synthetic grammar (comparable to German, though considerably more conservative and synthetic) and is distinguished by a wide assortment of irregular declensions. Icelandic vocabulary is also deeply conservative, with the country's language regulator maintaining an active policy of coining terms based on older Icelandic words rather than directly taking in loanwords from other languages.

Aside from the 300,000 Icelandic speakers in Iceland, Icelandic is spoken by about 8,000 people in Denmark,[4] 5,000 people in the United States,[5] and more than 1,400 people in Canada,[6] notably in the region known as New Iceland in Manitoba which was settled by Icelanders beginning in the 1880s.

The state-funded Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies serves as a centre for preserving the medieval Icelandic manuscripts and studying the language and its literature. The Icelandic Language Council, comprising representatives of universities, the arts, journalists, teachers, and the Ministry of Culture, Science and Education, advises the authorities on language policy. Since 1995, on 16 November each year, the birthday of 19th-century poet Jónas Hallgrímsson is celebrated as Icelandic Language Day.[7]

- ^ Icelandic at Ethnologue (26th ed., 2023)

- ^ Icelandic language at Ethnologue (19th ed., 2016)

- ^ Barbour & Carmichael 2000, p. 106.

- ^ "StatBank Denmark". www.statbank.dk.

- ^ "Icelandic". MLA Language Map Data Center. Modern Language Association. Archived from the original on 6 December 2010. Retrieved 17 April 2010. Based on 2000 US census data.

- ^ Government of Canada (8 May 2013). "2011 National Household Survey: Data tables". Statistics Canada.

- ^ "Icelandic: At Once Ancient And Modern" (PDF). Icelandic Ministry of Education, Science and Culture. 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 August 2019. Retrieved 27 April 2007.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).