Back صك غفران Arabic صكوك الغفران ARZ İndulgensiya Azerbaijani باغیش نامه AZB Індульгенцыя Byelorussian Индулгенция Bulgarian Oprost BS Indulgència Catalan Odpustek Czech Maddeueb Welsh

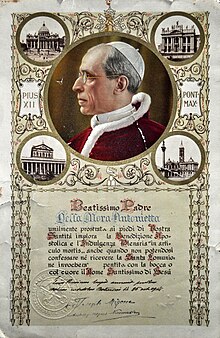

In the teaching of the Catholic Church, an indulgence (Latin: indulgentia, from indulgeo, 'permit') is "a way to reduce the amount of punishment one has to undergo for (forgiven) sins".[1] The Catechism of the Catholic Church describes an indulgence as "a remission before God of the temporal punishment due to sins whose guilt has already been forgiven, which the faithful Christian who is duly disposed gains under certain prescribed conditions…"[3]

The recipient of an indulgence must perform an action to receive it. This is most often the saying (once, or many times) of a specified prayer, but may also include a pilgrimage, the visiting of a particular place (such as a shrine, church or cemetery) or the performance of specific good works.[4]

Indulgences were introduced to allow for the remission of the severe penances of the early church and granted at the intercession of Christians awaiting martyrdom or at least imprisoned for the faith.[5] The Catholic church teaches that indulgences draw on the treasury of merit accumulated by Jesus' death on the cross and the virtues and penances of the saints.[6] They are granted for specific good works and prayers[6] in proportion to the devotion with which those good works are performed or prayers recited.[7]

By the late Middle Ages, indulgences were used to support charities for the public good, including hospitals.[8] However, the abuse of indulgences, mainly through commercialization, had become a serious problem which the church recognized but was unable to restrain effectively.[9] Indulgences were, from the beginning of the Protestant Reformation, a target of attacks by Martin Luther and other Protestant theologians. Eventually, the Catholic Counter-Reformation curbed the abuses of indulgences, but indulgences continue to play a role in modern Catholic religious life, and were dogmatically confirmed as part of the Catholic faith by the Council of Trent. In 1567, Pope Pius V forbade tying indulgences to any financial act, even to the giving of alms. Reforms in the 20th century largely abolished the quantification of indulgences, which had been expressed in terms of days or years. These days or years were meant to represent the equivalent of time spent in penance, although it was widely mistaken to mean time spent in Purgatory. The reforms also greatly reduced the number of indulgences granted for visiting particular churches and other locations.[citation needed]

- ^ Peters, Edward (2008). A Modern Guide to Indulgences: Rediscovering This Often Misinterpreted Teaching. Liturgy Training Publications. p. 13. ISBN 9781595250247.

- ^ "Catechism of the Catholic Church – IntraText". www.vatican.va.

- ^ "… through the action of the Church which, as the minister of redemption, dispenses and applies with authority the treasury of the satisfactions of Christ and all of the saints".[2]

- ^ Francis Xavier Lasance. "What is an Indulgence? – Indulgenced Prayers". From With God: a book of prayers and reflections (1911).

- ^ Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005, article indulgences

- ^ a b Wetterau, Bruce. World history. New York: Henry Holt and company. 1994.

- ^ "Indulgentiarum doctrina, chapter 5 and norm 5".

- ^ David Michael D'Andrea (2007). Civic Christianity in Renaissance Italy: The Hospital of Treviso, 1400–1530. University Rochester Press. pp. 15–. ISBN 978-1-58046-239-6.

- ^ Kent, William. "Indulgences." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 7. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. 9 July 2019

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.