Back Inflasie Afrikaans Inflation ALS تضخم اقتصادي Arabic تضخم اقتصادى ARZ মুদ্ৰাস্ফীতি Assamese Inflación AST İnflyasiya Azerbaijani تورم AZB Инфляция Bashkir Inflazion BAR

| Part of a series on |

| Macroeconomics |

|---|

|

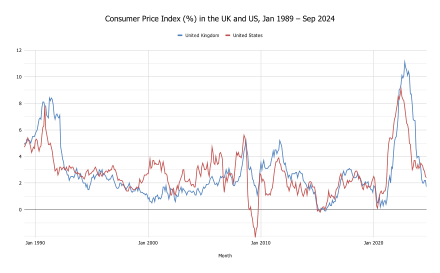

In economics, inflation is a general increase in the prices of goods and services in an economy. This is usually measured using a consumer price index (CPI).[3][4][5][6] When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services; consequently, inflation corresponds to a reduction in the purchasing power of money.[7][8] The opposite of CPI inflation is deflation, a decrease in the general price level of goods and services. The common measure of inflation is the inflation rate, the annualized percentage change in a general price index.[9] As prices faced by households do not all increase at the same rate, the consumer price index (CPI) is often used for this purpose.

Changes in inflation are widely attributed to fluctuations in real demand for goods and services (also known as demand shocks, including changes in fiscal or monetary policy), changes in available supplies such as during energy crises (also known as supply shocks), or changes in inflation expectations, which may be self-fulfilling.[10] Moderate inflation affects economies in both positive and negative ways. The negative effects would include an increase in the opportunity cost of holding money, uncertainty over future inflation, which may discourage investment and savings, and, if inflation were rapid enough, shortages of goods as consumers begin hoarding out of concern that prices will increase in the future. Positive effects include reducing unemployment due to nominal wage rigidity,[11] allowing the central bank greater freedom in carrying out monetary policy, encouraging loans and investment instead of money hoarding, and avoiding the inefficiencies associated with deflation.

Today, some economists favour a low and steady rate of inflation, though inflation is less popular with the general public than with economists, since "...inflation simultaneously transfers some of [the] people’s income into the hands of government."[12] Low (as opposed to zero or negative) inflation reduces the probability of economic recessions by enabling the labor market to adjust more quickly in a downturn and reduces the risk that a liquidity trap prevents monetary policy from stabilizing the economy while avoiding the costs associated with high inflation.[13] The task of keeping the rate of inflation low and stable is usually given to central banks that control monetary policy, normally through the setting of interest rates and by carrying out open market operations.[10]

- ^ "Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U): U.S. city average, by expenditure category, March 2022". Bureau of Labor Statistics. March 2022. Retrieved March 12, 2022.

- ^ "CPIH Annual Rate 00: All Items 2015=100". Office for National Statistics. April 13, 2022. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ^ What Is Inflation?, Cleveland Federal Reserve, June 8, 2023, archived from the original on March 30, 2021, retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ^ "Overview of BLS Statistics on Inflation and Prices : U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics". Bureau of Labor Statistics. June 5, 2019. Archived from the original on December 10, 2021. Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- ^ Salwati, Nasiha; Wessel, David (June 28, 2021). "How does the government measure inflation?". Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on November 15, 2021. Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- ^ "The Fed – What is inflation and how does the Federal Reserve evaluate changes in the rate of inflation?". Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. September 9, 2016. Archived from the original on July 17, 2021. Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- ^ Why price stability? Archived October 14, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Central Bank of Iceland, Accessed on September 11, 2008.

- ^ Paul H. Walgenbach, Norman E. Dittrich and Ernest I. Hanson, (1973), Financial Accounting, New York: Harcourt Brace Javonovich, Incorporated. P. 429. "The Measuring Unit principle: The unit of measure in accounting shall be the base money unit of the most relevant currency. This principle also assumes that the unit of measure is stable; that is, changes in its general purchasing power are not considered sufficiently important to require adjustments to the basic financial statements."

- ^ Mankiw 2002, pp. 22–32.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Blanchardwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Mankiw 2002, pp. 238–255.

- ^ Hummel, Jeffrey Rogers. "Death and Taxes, Including Inflation: the Public versus Economists". econjwatch.org. Econ Journal Watch: inflation, deadweight loss, deficit, money, national debt, seigniorage, taxation, velocity. p. 56. Retrieved November 19, 2023.

- ^ Svensson, Lars E. O. (December 2003). "Escaping from a Liquidity Trap and Deflation: The Foolproof Way and Others". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 17 (4): 145–166. doi:10.1257/089533003772034934. ISSN 0895-3309. S2CID 17420811.