Back Исаак Ньютон ADY Isaac Newton Afrikaans Isaac Newton ALS አይሳክ ኒውተን Amharic Isaac Newton AN Isaac Newton ANG Aisik Newtọn ANN आइजक न्यूटन ANP إسحاق نيوتن Arabic ܐܝܣܚܩ ܢܝܘܛܢ ARC

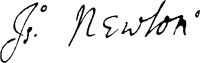

Sir Isaac Newton FRS (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27[a]) was an English polymath active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author who was described in his time as a natural philosopher.[6] He was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment that followed.[7][8] His pioneering book Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy), first published in 1687, achieved the first great unification in physics and established classical mechanics.[9][10] Newton made seminal contributions to optics, and shares credit with German mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz for formulating infinitesimal calculus, though he developed calculus years before Leibniz.[11][12] He contributed to and refined the scientific method, and his work is considered the most influential in bringing forth modern science.[13][14][15][16][17]

In the Principia, Newton formulated the laws of motion and universal gravitation that formed the dominant scientific viewpoint for centuries until it was superseded by the theory of relativity. He used his mathematical description of gravity to derive Kepler's laws of planetary motion, account for tides, the trajectories of comets, the precession of the equinoxes and other phenomena, eradicating doubt about the Solar System's heliocentricity.[18] He demonstrated that the motion of objects on Earth and celestial bodies could be accounted for by the same principles. Newton's inference that the Earth is an oblate spheroid was later confirmed by the geodetic measurements of Maupertuis, La Condamine, and others, convincing most European scientists of the superiority of Newtonian mechanics over earlier systems.

Newton built the first practical reflecting telescope and developed a sophisticated theory of colour based on the observation that a prism separates white light into the colours of the visible spectrum. His work on light was collected in his highly influential book Opticks, published in 1704. He formulated an empirical law of cooling, which was the first heat transfer formulation,[19] made the first theoretical calculation of the speed of sound, and introduced the notion of a Newtonian fluid. Furthermore, he made early investigations into electricity,[20][21] with an idea from his book Opticks arguably the beginning of the field theory of the electric force.[22] In addition to his work on calculus, as a mathematician, Newton contributed to the study of power series, generalised the binomial theorem to non-integer exponents, developed a method for approximating the roots of a function, and classified most of the cubic plane curves.

Newton was a fellow of Trinity College and the second Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge. He was a devout but unorthodox Christian who privately rejected the doctrine of the Trinity. He refused to take holy orders in the Church of England, unlike most members of the Cambridge faculty of the day. Beyond his work on the mathematical sciences, Newton dedicated much of his time to the study of alchemy and biblical chronology, but most of his work in those areas remained unpublished until long after his death. Politically and personally tied to the Whig party, Newton served two brief terms as Member of Parliament for the University of Cambridge, in 1689–1690 and 1701–1702. He was knighted by Queen Anne in 1705 and spent the last three decades of his life in London, serving as Warden (1696–1699) and Master (1699–1727) of the Royal Mint, in which he increased the accuracy and security of British coinage,[23][24] as well as president of the Royal Society (1703–1727).

- ^ "Fellows of the Royal Society". London: Royal Society. Archived from the original on 16 March 2015.

- ^ Feingold, Mordechai. Barrow, Isaac (1630–1677) Archived 29 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, September 2004; online edn, May 2007. Retrieved 24 February 2009; explained further in Feingold, Mordechai (1993). "Newton, Leibniz, and Barrow Too: An Attempt at a Reinterpretation". Isis. 84 (2): 310–338. Bibcode:1993Isis...84..310F. doi:10.1086/356464. ISSN 0021-1753. JSTOR 236236. S2CID 144019197.

- ^ "Dictionary of Scientific Biography". Notes, No. 4. Archived from the original on 25 February 2005.

- ^ Kevin C. Knox, Richard Noakes (eds.), From Newton to Hawking: A History of Cambridge University's Lucasian Professors of Mathematics, Cambridge University Press, 2003, p. 61.

- ^ Thony, Christie (2015). "Calendrical confusion or just when did Newton die?". The Renaissance Mathematicus. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ^ Alex, Berezow (4 February 2022). "Who was the smartest person in the world?". Big Think. Archived from the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 28 September 2023.

- ^ Matthews, Michael R. (2000), "The Pendulum in Newton's Physics", Time for Science Education, vol. 8, Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 181–213, doi:10.1007/978-94-011-3994-6_8, ISBN 978-0-306-45880-4, retrieved 14 November 2024

- ^ Cartwright, Mark (19 September 2023). "Isaac Newton". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 14 November 2024.

- ^ Rynasiewicz, Robert A. (22 August 2011), "Newton's Views on Space, Time, and Motion", Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Stanford University, retrieved 15 November 2024

- ^ Klaus Mainzer (2 December 2013). Symmetries of Nature: A Handbook for Philosophy of Nature and Science. Walter de Gruyter. p. 8. ISBN 978-3-11-088693-1.

- ^ Boyer, Carl B. (1970). "The History of the Calculus". The Two-Year College Mathematics Journal. 1 (1): 60. doi:10.2307/3027118.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:3was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Westfall, Richard S. (1981). "The Career of Isaac Newton: A Scientific Life in the Seventeenth Century". The American Scholar. 50 (3): 341–353. ISSN 0003-0937.

- ^ Tyson, Peter (15 November 2005). "Newton's Legacy". www.pbs.org. Retrieved 14 November 2024.

- ^ Carpi, Anthony; Egger, Anne E. (2011). The Process of Science (Revised ed.). Visionlearning. pp. 91–92. ISBN 978-1-257-96132-0.

- ^ Iliffe, Rob; Smith, George E., eds. (2016). The Cambridge Companion to Newton (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 1, 4, 12–16. doi:10.1017/cco9781139058568. ISBN 978-1-139-05856-8.

- ^ Snobelen, Stephen D. (24 February 2021), "Isaac Newton", Renaissance and Reformation, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/obo/9780195399301-0462, ISBN 978-0-19-539930-1, retrieved 15 November 2024

- ^ More, Louis Trenchard (1934). Isaac Newton, a Biography. Dover Publications. p. 327.

- ^ Cheng, K. C.; Fujii, T. (1998). "Isaac Newton and Heat Transfer". Heat Transfer Engineering. 19 (4): 9–21. doi:10.1080/01457639808939932. ISSN 0145-7632.

- ^ The Encyclopaedia Britannica: Or, Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and General Literature. Vol. VIII. Adam and Charles Black. 1855. p. 524.

- ^ Sanford, Fernando (1921). "Some Early Theories Regarding Electrical Forces – The Electric Emanation Theory". The Scientific Monthly. 12 (6): 544–550. Bibcode:1921SciMo..12..544S. ISSN 0096-3771.

- ^ Rowlands, Peter (2017). Newton - Innovation And Controversy. World Scientific Publishing. p. 109. ISBN 9781786344045.

- ^ Belenkiy, Ari (1 February 2013). "The Master of the Royal Mint: How Much Money did Isaac Newton Save Britain?". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series A: Statistics in Society. 176 (2): 481–498. doi:10.1111/j.1467-985X.2012.01037.x. ISSN 0964-1998.

- ^ Marples, Alice (20 September 2022). "The science of money: Isaac Newton's mastering of the Mint". Notes and Records: the Royal Society Journal of the History of Science. 76 (3): 507–525. doi:10.1098/rsnr.2021.0033. ISSN 0035-9149.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).