Back Jacques Derrida Afrikaans جاك دريدا Arabic جاك دريدا ARZ Jacques Derrida AST Jak Derrida Azerbaijani Жак Дэрыда Byelorussian Жак Дэрыда BE-X-OLD Жак Дерида Bulgarian জাক দেরিদা Bengali/Bangla Jacques Derrida BS

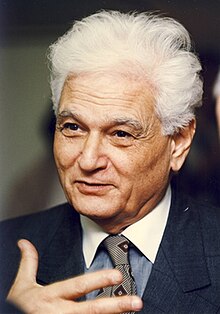

Jacques Derrida | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Jackie Élie Derrida 15 July 1930 |

| Died | 9 October 2004 (aged 74) Paris, France |

| Education | École normale supérieure (BA, MA, Dr. cand.) Harvard University University of Paris (DrE) |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 3, including Pierre Alféri |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | |

| Institutions | |

| Notable students | |

Notable ideas | |

Jacques Derrida (/ˈdɛrɪdə/; French: [ʒak dɛʁida]; born Jackie Élie Derrida;[6] 15 July 1930 – 9 October 2004) was a French philosopher. He developed the philosophy of deconstruction, which he utilized in a number of his texts, and which was developed through close readings of the linguistics of Ferdinand de Saussure and Husserlian and Heideggerian phenomenology.[7][8][9] He is one of the major figures associated with post-structuralism and postmodern philosophy[10][11][12] although he distanced himself from post-structuralism and disowned the word "postmodernity".[13]

During his career, Derrida published over 40 books, together with hundreds of essays and public presentations. He had a significant influence on the humanities and social sciences, including philosophy, literature, law,[14][15][16] anthropology,[17] historiography,[18] applied linguistics,[19] sociolinguistics,[20] psychoanalysis,[21] music, architecture, and political theory.

Into the 2000s, his work retained major academic influence throughout the United States,[22] continental Europe, South America and all other countries where continental philosophy has been predominant, particularly in debates around ontology, epistemology (especially concerning social sciences), ethics, aesthetics, hermeneutics, and the philosophy of language. In most of the Anglosphere, where analytic philosophy is dominant, Derrida's influence is most presently felt in literary studies due to his longstanding interest in language and his association with prominent literary critics from his time at Yale. He also influenced architecture (in the form of deconstructivism), music[23] (especially in the musical atmosphere of hauntology), art,[24] and art criticism.[25]

Particularly in his later writings, Derrida addressed ethical and political themes in his work. Some critics consider Speech and Phenomena (1967) to be his most important work. Others cite: Of Grammatology (1967) Writing and Difference (1967), and Margins of Philosophy (1972). These writings influenced various activists and political movements.[26] He became a well-known and influential public figure, while his approach to philosophy and the notorious abstruseness of his work made him controversial.[26][27]

- ^ John D. Caputo, Radical Hermeneutics: Repetition, Deconstruction, and the Hermeneutic Project, OCLC 729013297, Indiana University Press, 1988, p. 5: "Derrida is the turning point for radical hermeneutics, the point where hermeneutics is pushed to the brink. Radical hermeneutics situates itself in the space which is opened up by the exchange between Heidegger and Derrida..."

- ^ Horner, Robyn (2005). Jean-Luc Marion: a Theo-Logical Introduction. Burlington: Ashgate. p. 3.

- ^ Wroe, Nicholas (11 May 2002). "History's pallbearer". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Derrida, J: "How to Avoid Speaking: Denials", pp. 3–70, in "Languages of the Unsayable: The Play of Negativity in Literature and Literary Theory", Stanley Budick and Wolfgang Iser (eds). 198.

- ^ "Reading Derrida / Thinking Paul: On Justice – Theodore W. Jennings, Jr". www.sup.org. Archived from the original on 12 October 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- ^ Peeters (2013), pp. 12–13.

See also Bennington, Geoffrey (1993). Jacques Derrida. The University of Chicago Press. p. 325.Jackie was born at daybreak, on 15 July 1930, at El Biar, in the hilly suburbs of Algiers, in a holiday home. [...] The boy's main forename was probably chosen because of Jackie Coogan ... When he was circumcised, he was given a second forename, Elie, which was not entered on his birth certificate, unlike the equivalent names of his brother and sister.

1930 Birth of Jackie Derrida, July 15, in El-Biar (near Algiers, in a holiday house).

- ^ "Jacques Derrida". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- ^ Derrida on Religion: Thinker of Differance By Dawne McCance. Equinox. p. 7.

- ^ Derrida, Deconstruction, and the Politics of Pedagogy (Counterpoints Studies in the Postmodern Theory of Education). Peter Lang Publishing Inc. p. 134. OCLC 314727596, 476972726, 263497930, 783449163

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Bensmaia05was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Poster88was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Vincent B. Leitch Postmodernism: Local Effects, Global Flows, SUNY Series in Postmodern Culture (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1996), p. 27.

- ^ Augustine and Postmodernism, in response to George Heffernan of Merrimack College. Indiana University Press ISBN 0-253-34507-3 (cloth: alk. paper) — ISBN 0-253-21731-8 (pbk.: alk. paper) page 42:

If I missed, and I probably missed a number of things in your intervention, if I missed something essential please forgive me. First, I would protest against the word postmodernity. I never used this word. I’m not responsible for the use of this word here or anywhere else ...

- ^ Derrida, Jacques (1992). "Force of Law". In Drucilla Cornell; Michael Rosenfeld; David Gray Carlson (eds.). Deconstruction and the Possibility of Justice. Translated by Mary Quaintance (1st ed.). New York: Routledge. pp. 3–67. ISBN 978-0810103979.

A decision that did not go through the ordeal of the undecidable would not be a free decision, it would only be the programmable application or unfolding of a calculable process (...) deconstructs from the inside every assurance of presence, and thus every criteriology that would assure us of the justice of the decision.

- ^ "Critical Legal Studies Movement" in "The Bridge"

- ^ GERMAN LAW JOURNAL, SPECIAL ISSUE: A DEDICATION TO JACQUES DERRIDA Archived 16 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Vol. 6 No. 1, 1–243, 1 January 2005.

- ^ "Legacies of Derrida: Anthropology", Rosalind C. Morris, Annual Review of Anthropology, Volume: 36, pp. 355–389, 2007.

- ^ "Deconstructing History", published 1997 (2nd. edn. Routledge, 2006).

- ^ Busch, Brigitt (2012). "Linguistic Repertoire Revisited". Applied Linguistics. 33 (5): 503–523. doi:10.1093/applin/ams056.

- ^ "The sociolinguistics of schooling: the relevance of Derrida's Monolingualism of the Other or the Prosthesis of Origin", Michael Evans, 01/2012; ISBN 978-3-0343-1009-3. In Edith Esch and Martin Solly (eds.), The Sociolinguistics of Language Education in International Contexts, Peter Lang, pp. 31–46.

- ^ Earlie, Paul (2021). Derrida and the Legacy of Psychoanalysis. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198869276.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-886927-6.

- ^ Kandell, Jonathan (10 October 2004). "Jacques Derrida, Abstruse Theorist, Dies at 74". The New York Times.

- ^ "Deconstruction in Music – The Jacques Derrida", Gerd Zacher Encounter, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2002.

- ^ E.g., "Doris Salcedo", Phaidon (2004), "Hans Haacke", Phaidon (2000).

- ^ E.g. "The return of the real", Hal Foster, October – MIT Press (1996); "Kant after Duchamp", Thierry de Duve, October – MIT Press (1996); "Neo-Avantgarde and Cultural Industry – Essays on European and American Art from 1955 to 1975", Benjamin H.D. Buchloh, October – MIT Press (2000); "Perpetual Inventory", Rosalind E. Krauss, October – MIT Press, 2010.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

obituarywas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Lawlor, Leonard. "Jacques Derrida". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. plato.stanford.edu. 22 November 2006; last modified 6 October 2016. Retrieved 20 May 2017.