Back جون مارشال هارلان Arabic جون مارشال هارلان ARZ جان مارشال هارلان AZB John Marshall Harlan German John Marshall Harlan French ג'ון מרשל הרלן HE John Marshall Harlan ID John Marshall Harlan Polish John Marshall Harlan Portuguese Харлан, Джон Маршалл Russian

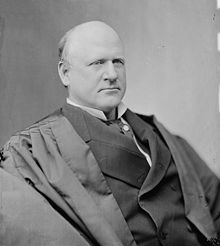

John Marshall Harlan | |

|---|---|

| |

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

| In office December 10, 1877 – October 14, 1911 | |

| Nominated by | Rutherford B. Hayes |

| Preceded by | David Davis |

| Succeeded by | Mahlon Pitney |

| Attorney General of Kentucky | |

| In office September 1, 1863 – September 3, 1867 | |

| Governor | Thomas Bramlette |

| Preceded by | Andrew James |

| Succeeded by | John Rodman |

| Personal details | |

| Born | June 1, 1833 Boyle County, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Died | October 14, 1911 (aged 78) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Rock Creek Cemetery Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party | Whig (before 1854) Know Nothing (1854–1858) Opposition (1858–1860) Constitutional Union (1860) Unionist (1861–1867) Republican (1868–1911) |

| Spouse | |

| Relations | John Marshall Harlan II (grandson), Robert James Harlan (brother) |

| Children | 6, including James and John Maynard |

| Parents |

|

| Education | Centre College (BA) Transylvania University |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Branch/service | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1861–1863 |

| Rank | Colonel |

| Unit | 10th Kentucky Infantry |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

John Marshall Harlan (June 1, 1833 – October 14, 1911) was an American lawyer and politician who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1877 until his death in 1911. He is often called "The Great Dissenter" due to his many dissents in cases that restricted civil liberties, including the Civil Rights Cases, Plessy v. Ferguson, and Giles v. Harris. Many of Harlan's views expressed in his notable dissents would become the official view of the Supreme Court starting from the 1950s Warren Court and onward.

Born into a prominent, slave-holding family near Danville, Kentucky, Harlan experienced a quick rise to political prominence. When the American Civil War broke out, Harlan strongly supported the Union and recruited the 10th Kentucky Infantry. Despite his opposition to the Emancipation Proclamation, he served in the war until 1863, when he was elected attorney general of Kentucky. Harlan lost his re-election bid in 1867 and joined the Republican Party in the following year, quickly emerging as the leader of the Kentucky Republican Party. In 1877, President Rutherford B. Hayes appointed Harlan to the Supreme Court.

Harlan's jurisprudence was marked by his life-long belief in a strong national government, his sympathy for the economically disadvantaged, and his view that the Reconstruction Amendments had fundamentally transformed the relationship between the federal government and the state governments. He was the sole dissenter in both the Civil Rights Cases (1883) and Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), which permitted state and private actors to engage in ethnic segregation. He also wrote dissents in major cases such as Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co. (1895), which struck down a federal income tax; United States v. E. C. Knight Co. (1895), which severely limited the power of the federal government to pursue antitrust actions; Lochner v. New York (1905), which invalidated a state law setting maximum working hours on the basis of substantive due process; and Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey v. United States (1911), which established the rule of reason. He was the first Supreme Court justice to advocate the incorporation of the Bill of Rights, and his majority opinion in Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad Co. v. City of Chicago (1897) incorporated the Takings Clause.

Harlan was largely forgotten in the decades after his death but many scholars now consider him to be one of the greatest Supreme Court justices of his era. His grandson John Marshall Harlan II later served on the Supreme Court from 1955 to 1971.