Back مشروع إصلاح إجراءات القضاء 1937 Arabic Projet de loi sur la réforme des procédures judiciaires de 1937 (États-Unis) French Законопроект о расширении состава Верховного суда США (1937) Russian 1937年司法程序改革法案 Chinese

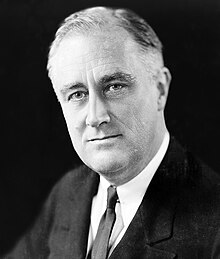

The Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937,[1] frequently called the "court-packing plan",[2] was a legislative initiative proposed by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt to add more justices to the U.S. Supreme Court in order to obtain favorable rulings regarding New Deal legislation that the Court had ruled unconstitutional.[3] The central provision of the bill would have granted the president power to appoint an additional justice to the U.S. Supreme Court, up to a maximum of six, for every member of the court over the age of 70 years.

In the Judiciary Act of 1869, Congress had established that the Supreme Court would consist of the chief justice and eight associate justices. During Roosevelt's first term, the Supreme Court struck down several New Deal measures as being unconstitutional. Roosevelt sought to reverse this by changing the makeup of the court through the appointment of new additional justices who he hoped would rule that his legislative initiatives did not exceed the constitutional authority of the government. Since the U.S. Constitution does not define the Supreme Court's size, Roosevelt believed it was within the power of Congress to change it. Members of both parties viewed the legislation as an attempt to stack the court, and many Democrats, including Vice President John Nance Garner, opposed it.[4][5] The bill came to be known as Roosevelt's "court-packing plan", a phrase coined by Edward Rumely.[2]

In November 1936, Roosevelt won a sweeping re-election victory. In the months following, he proposed to reorganize the federal judiciary by adding a new justice each time a justice reached age 70 and failed to retire.[6] The legislation was unveiled on February 5, 1937, and was the subject of Roosevelt's ninth fireside chat on March 9, 1937.[7][8] He asked, "Can it be said that full justice is achieved when a court is forced by the sheer necessity of its business to decline, without even an explanation, to hear 87% of the cases presented by private litigants?" Publicly denying the president's statement, Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes reported, "There is no congestion of cases on our calendar. When we rose March 15 we had heard arguments in cases in which cert has been granted only four weeks before. This gratifying situation has obtained for several years".[9] Three weeks after the radio address, the Supreme Court published an opinion upholding a Washington state minimum wage law in West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish.[10] The 5–4 ruling was the result of the apparently sudden jurisprudential shift by Associate Justice Owen Roberts, who joined with the wing of the bench supportive to the New Deal legislation. Since Roberts had previously ruled against most New Deal legislation, his support here was seen as a result of the political pressure the president was exerting on the court. Some interpreted Roberts' reversal as an effort to maintain the Court's judicial independence by alleviating the political pressure to create a court more friendly to the New Deal. This reversal came to be known as "the switch in time that saved nine"; however, recent legal-historical scholarship has called that narrative into question[11] as Roberts' decision and vote in the Parrish case predated both the public announcement and introduction of the 1937 bill.[12]

Roosevelt's legislative initiative ultimately failed. Henry F. Ashurst, the Democratic chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee, held up the bill by delaying hearings in the committee, saying, "No haste, no hurry, no waste, no worry—that is the motto of this committee."[13] As a result of his delaying efforts, the bill was held in committee for 165 days, and opponents of the bill credited Ashurst as instrumental in its defeat.[5] The bill was further undermined by the untimely death of its chief advocate in the U.S. Senate, Senate Majority Leader Joseph T. Robinson. Other reasons for its failure included members of Roosevelt's own Democratic Party believing the bill to be unconstitutional, with the Judiciary Committee ultimately releasing a scathing report calling it "a needless, futile and utterly dangerous abandonment of constitutional principle ... without precedent or justification".[14][9] Contemporary observers broadly viewed Roosevelt's initiative as political maneuvering. Its failure exposed the limits of Roosevelt's abilities to push forward legislation through direct public appeal. Public perception of his efforts here was in stark contrast to the reception of his legislative efforts during his first term.[15][16] Roosevelt ultimately prevailed in establishing a majority on the court friendly to his New Deal legislation, though some scholars view Roosevelt's victory as pyrrhic.[16]

- ^ Parrish, Michael E. (2002). The Hughes Court: Justices, Rulings, and Legacy. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, Inc. p. 24. ISBN 9781576071977. Retrieved October 31, 2013.

- ^ a b Epstein, at 451.

- ^ Leuchtenburg, at 115ff.

- ^ Sean J. Savage (1991). Roosevelt, the Party Leader, 1932–1945. University Press of Kentucky. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-8131-1755-3.

- ^ a b "Ashurst, Defeated, Reviews Service". The New York Times. September 12, 1940. p. 18.

- ^ Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum (December 11, 2015). "Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Supreme Court". Presidential Timeline of the National Archives and Records Administration. Presidential Libraries of the National Archives and Records Administration. Archived from the original on December 6, 2015.

- ^ "Fireside Chat (March 9, 1937)". The American Presidency Project.

- ^ Winfield, Betty (1990). FDR and the news media. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. p. 104. ISBN 0-252-01672-6.

- ^ a b Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Reorganization of the Federal Judiciary, S. Rep. No. 711, 75th Congress, 1st Session, 1 (1937).

- ^ 300 U.S. 379 (1937)

- ^ White, at 308.

- ^ McKenna, at 413.

- ^ Baker, Richard Allan (1999). "Ashurst, Henry Fountain". In Garraty, John A.; Carnes, Mark C. (eds.). American National Biography. Vol. 1. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 686–687. ISBN 0-19-512780-3.

- ^ "TSHA | Court-Packing Plan of 1937".

- ^ Ryfe, David Michael (1999). "Franklin Roosevelt and the fireside chats". The Journal of Communication. 49 (4): 80–103 [98–99]. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1999.tb02818.x. Archived from the original on January 5, 2013.

- ^ a b Leuchtenburg, at 156–161.