Back لغة لاكوتا Arabic لاكوتا (لغه) ARZ Lakota (Sproch) BAR Lakota (llengua) Catalan Lakotština Czech Lakota (sprog) Danish Lakota (Sprache) German Lakota lingvo Esperanto Lakota keel Estonian زبان لاکوتا Persian

A major contributor to this article appears to have a close connection with its subject. (December 2021) |

| Lakota | |

|---|---|

| Lakȟótiyapi | |

| Pronunciation | [laˈkˣɔtɪjapɪ] |

| Native to | United States, with some speakers in Canada |

| Region | Primarily North Dakota and South Dakota, but also northern Nebraska, southern Minnesota, and northern Montana |

| Ethnicity | Teton Sioux |

Native speakers | (2,100, 29% of ethnic population cited 1997–2016)[1] |

Siouan

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | lkt |

| Glottolog | lako1247 |

| ELP | Lakota |

Map of core pre-contact Lakota territory | |

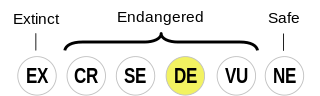

Lakota is classified as Definitely Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger. | |

| Lakota "ally / friend" | |

|---|---|

| People | Lakȟóta Oyáte |

| Language | Lakȟótiyapi |

| Country | Lakȟóta Makóce, Očhéthi Šakówiŋ |

Lakota (Lakȟótiyapi [laˈkˣɔtɪjapɪ]), also referred to as Lakhota, Teton or Teton Sioux, is a Siouan language spoken by the Lakota people of the Sioux tribes. Lakota is mutually intelligible with the two dialects of the Dakota language, especially Western Dakota, and is one of the three major varieties of the Sioux language.

Speakers of the Lakota language make up one of the largest Native American language speech communities in the United States, with approximately 2,000 speakers, who live mostly in the northern plains states of North Dakota and South Dakota.[1] Many communities have immersion programs for both children and adults.

Like many indigenous languages, the Lakota language did not have a written form traditionally. However, efforts to develop a written form of Lakota began, primarily through the work of Christian missionaries and linguists, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The orthography has since evolved to reflect contemporary needs and usage.

One significant figure in the development of a written form of Lakota was Ella Cara Deloria, also called Aŋpétu Wašté Wiŋ (Beautiful Day Woman), a Yankton Dakota ethnologist, linguist, and novelist who worked extensively with the Dakota and Lakota peoples, documenting their languages and cultures. She collaborated with linguists such as Franz Boas and Edward Sapir to create written materials for Lakota, including dictionaries and grammars.[2]

Another key figure was Albert White Hat Sr., who taught at and later became the chair of the Lakota language program at his alma mater, Sinte Gleska University at Mission, South Dakota, one of the first tribal-based universities in the US.[3] His work focused on the Sicangu dialect using an orthography developed by Lakota in 1982 and which today is slowly supplanting older systems provided by linguists and missionaries.

- ^ a b Lakota at Ethnologue (25th ed., 2022)

- ^ "Ella Cara Deloria". Association for Women in Science. Association for Women in Science. Retrieved 22 February 2024.

- ^ "Winged Messenger Nations: Birds in American Indian Oral Tradition: Albert White Hat Sr. & Francis Cut". The Winged Messenger Project. The Winged Messenger Project. Retrieved 22 February 2024.