Back قيثارة سومرية Arabic قيثاره سومريه ARZ Arpes d'Ur Catalan Έγχορδα όργανα μουσικής του Ουρ Greek Liras de Ur Spanish چنگهای اور Persian Harpes d'Ur French Uri hárfák és lírák Hungarian Arpe e lire di Ur Italian Arpas d'Ur Occitan

The Lyres of Ur or Harps of Ur is a group of four string instruments excavated in a fragmentary condition at the Royal Cemetery at Ur in modern Iraq from 1922 onwards. They date back to the Early Dynastic III Period of Mesopotamia, between about 2550 and 2450 BC, making them the world's oldest surviving stringed instruments.[1] Carefully restored and reconstructed, they are now divided between museums in Iraq, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

Strictly speaking, three lyres and one harp were unearthed, but all are often called lyres. The instrument remains were restored and distributed between the museums that took part in the excavations. The "Golden Lyre of Ur" or "Bull's Lyre", the finest, is in the Iraq Museum in Baghdad. The British Museum in London has the "Queen's Lyre" and "Silver Lyre", and the Penn Museum in Philadelphia has the "Bull-Headed Lyre".

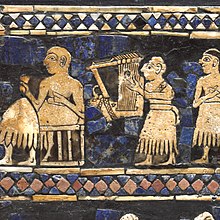

In 1929, archaeologists led by the British archaeologist Leonard Woolley, representing a joint expedition of the British Museum and the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, found the instruments while excavating the Royal Cemetery at Ur. They excavated pieces of three lyres and one harp in Ur, located in what was Ancient Mesopotamia and is contemporary Iraq.[2][3] They are over 4,500 years old,[4] from ancient Mesopotamia during the Early Dynastic III Period (2550–2450 BC).[5] The decorations on the lyres are fine examples of the court art of Mesopotamia of the period.[6]

Leonard Woolley dug up the lyres from amongst the skeletons of ten women in the Royal Cemetery at Ur. One skeleton was even said to be lying against the lyre with her hand placed where the strings would have been.[4] Woolley was quick to pour in a liquid plaster to recover the delicate form of the wooden frame.[7] The wood of the lyres was decayed but since some were covered in nonperishable materials, like gold and silver, they were able to be taken.[8]

- ^ Michael Chanan (1994). Musica Practica: The Social Practice of Western Music from Gregorian Chant to Postmodernism. Verso. p. 170. ISBN 978-1-85984-005-4.

- ^ "Ancient Iraqi harp reproduced by Liverpool engineers" (Press release). University of Liverpool. 28 July 2005. Archived from the original on 1 July 2010. Retrieved 2009-11-23.

A team of engineers at the University of Liverpool has helped reproduce an ancient Iraqi harp - the Lyre of Ur

- ^ Taylor, Bill. "Golden Lyre of Ur". Archived from the original on 2011-06-11.

- ^ a b "Queen's Lyre". British Museum. Retrieved 2017-03-22.

- ^ "Lyre with bearded bull's head and inlaid panel". With Art Philadelphia. Retrieved 2015-09-26.

- ^ Aruz, J.; Wallenfels (2003). Art of the First Cities: The third millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. New York, NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Mctaguewas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Lawergren, Bo (November 2005). "Two Lyres from Ur". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. doi:10.1086/BASOR25066917. Retrieved 21 October 2015.