Back Macrofago AN خلية بلعمية كبيرة Arabic Makrofaqlar Azerbaijani Макрофаг Bulgarian ম্যাক্রোফেজ Bengali/Bangla Makrofag BS Macròfag Catalan ماکرۆفەیج CKB Makrofág Czech Makrofag Danish

| Macrophage | |

|---|---|

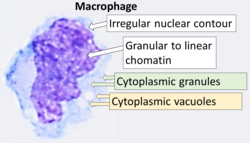

Cytology of a macrophage with typical features. Wright stain. | |

| Details | |

| Pronunciation | /ˈmakrə(ʊ)feɪdʒ/ |

| System | Immune system |

| Function | Phagocytosis |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | macrophagocytus |

| Acronym(s) | Mφ, MΦ |

| MeSH | D008264 |

| TH | H2.00.03.0.01007 |

| FMA | 63261 |

| Anatomical terms of microanatomy | |

Macrophages (/ˈmækroʊfeɪdʒ/; abbreviated Mφ, MΦ or MP) are a type of white blood cell of the innate immune system that engulf and digest pathogens, such as cancer cells, microbes, cellular debris, and foreign substances, which do not have proteins that are specific to healthy body cells on their surface.[1][2] This process is called phagocytosis, which acts to defend the host against infection and injury.[3]

Macrophages are found in essentially all tissues,[4] where they patrol for potential pathogens by amoeboid movement. They take various forms (with various names) throughout the body (e.g., histiocytes, Kupffer cells, alveolar macrophages, microglia, and others), but all are part of the mononuclear phagocyte system. Besides phagocytosis, they play a critical role in nonspecific defense (innate immunity) and also help initiate specific defense mechanisms (adaptive immunity) by recruiting other immune cells such as lymphocytes. For example, they are important as antigen presenters to T cells. In humans, dysfunctional macrophages cause severe diseases such as chronic granulomatous disease that result in frequent infections.

Beyond increasing inflammation and stimulating the immune system, macrophages also play an important anti-inflammatory role and can decrease immune reactions through the release of cytokines. Macrophages that encourage inflammation are called M1 macrophages, whereas those that decrease inflammation and encourage tissue repair are called M2 macrophages.[5] This difference is reflected in their metabolism; M1 macrophages have the unique ability to metabolize arginine to the "killer" molecule nitric oxide, whereas M2 macrophages have the unique ability to metabolize arginine to the "repair" molecule ornithine.[6] However, this dichotomy has been recently questioned as further complexity has been discovered.[7]

Human macrophages are about 21 micrometres (0.00083 in) in diameter[8] and are produced by the differentiation of monocytes in tissues. They can be identified using flow cytometry or immunohistochemical staining by their specific expression of proteins such as CD14, CD40, CD11b, CD64, F4/80 (mice)/EMR1 (human), lysozyme M, MAC-1/MAC-3 and CD68.[9]

Macrophages were first discovered and named by Élie Metchnikoff, a Russian Empire zoologist, in 1884.[10][11]

- ^ Mahla RS, Kumar A, Tutill HJ, Krishnaji ST, Sathyamoorthy B, Noursadeghi M, et al. (January 2021). "NIX-mediated mitophagy regulate metabolic reprogramming in phagocytic cells during mycobacterial infection". Tuberculosis. 126 (January): 102046. doi:10.1016/j.tube.2020.102046. PMID 33421909. S2CID 231437641.

- ^ "Regenerative Medicine Partnership in Education". Archived from the original on 25 April 2015. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- ^ Nahrendorf M, Hoyer FF, Meerwaldt AE, van Leent MM, Senders ML, Calcagno C, et al. (October 2020). "Imaging Cardiovascular and Lung Macrophages With the Positron Emission Tomography Sensor 64Cu-Macrin in Mice, Rabbits, and Pigs". Circulation: Cardiovascular Imaging. 13 (10): e010586. doi:10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.120.010586. PMC 7583675. PMID 33076700.

- ^ Ovchinnikov DA (September 2008). "Macrophages in the embryo and beyond: much more than just giant phagocytes". Genesis. 46 (9): 447–462. doi:10.1002/dvg.20417. PMID 18781633. S2CID 38894501.

Macrophages are present essentially in all tissues, beginning with embryonic development and, in addition to their role in host defense and in the clearance of apoptotic cells, are being increasingly recognized for their trophic function and role in regeneration.

- ^ Mills CD (2012). "M1 and M2 Macrophages: Oracles of Health and Disease". Critical Reviews in Immunology. 32 (6): 463–488. doi:10.1615/CritRevImmunol.v32.i6.10. PMID 23428224.

- ^ Murphy K, Weaver C (2006). Janeway's immunobiology. Garland Science, New York. pp. 464, 904. ISBN 978-0-8153-4551-0.

- ^ Ransohoff RM (July 2016). "A polarizing question: do M1 and M2 microglia exist?". Nature Neuroscience. 19 (8): 987–991. doi:10.1038/nn.4338. PMID 27459405. S2CID 27541569.

- ^ Krombach F, Münzing S, Allmeling AM, Gerlach JT, Behr J, Dörger M (September 1997). "Cell size of alveolar macrophages: an interspecies comparison". Environmental Health Perspectives. 105 (Suppl 5): 1261–1263. doi:10.2307/3433544. JSTOR 3433544. PMC 1470168. PMID 9400735.

- ^ Khazen W, M'bika JP, Tomkiewicz C, Benelli C, Chany C, Achour A, et al. (October 2005). "Expression of macrophage-selective markers in human and rodent adipocytes". FEBS Letters. 579 (25): 5631–5634. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2005.09.032. PMID 16213494. S2CID 6066984.

- ^ Zalkind S (2001). Ilya Mechnikov: His Life and Work. Honolulu, Hawaii: University Press of the Pacific. pp. 78, 210. ISBN 978-0-89875-622-7.

- ^ Shapouri-Moghaddam A, Mohammadian S, Vazini H, Taghadosi M, Esmaeili SA, Mardani F, et al. (September 2018). "Macrophage plasticity, polarization, and function in health and disease". Journal of Cellular Physiology. 233 (9): 6425–6440. doi:10.1002/jcp.26429. PMID 29319160. S2CID 3621509.