Back معجزة تشيلي Arabic Milagro de Chile Spanish معجزه شیلی Persian Chilen ihme Finnish Miracle chilien French Keajaiban Chili ID Miracolo del Cile Italian チリの奇跡 Japanese Miracol del Cile LMO Chilijski cud Polish

| Economic history of Chile |

|---|

|

This article's lead section may be too long. (December 2022) |

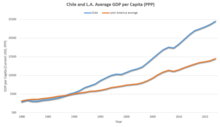

The "Miracle of Chile" was a term used by economist Milton Friedman to describe the reorientation of the Chilean economy in the 1980s and the effects of the economic policies applied by a large group of Chilean economists who collectively came to be known as the Chicago Boys, having studied at the University of Chicago where Friedman taught. He said the "Chilean economy did very well, but more importantly, in the end the central government, the military junta, was replaced by a democratic society. So the really important thing about the Chilean business is that free markets did work their way in bringing about a free society."[1] The junta to which Friedman refers was a military government that came to power in a 1973 coup d'état, which came to an end in 1990 after a democratic 1988 plebiscite removed Augusto Pinochet from the presidency.

The economic reforms implemented by the Chicago Boys had three main objectives: economic liberalization, privatization of state-owned companies, and stabilization of inflation. The first reforms were implemented in three rounds – 1974–1983, 1985, and 1990. The reforms were continued and strengthened after 1990 by the post-Pinochet center government of Patricio Aylwin's Christian Democrats.[2] However, the center-left government of Eduardo Frei Ruiz-Tagle also made a commitment to poverty reduction. In 1988, 48% of Chileans lived below the poverty line. By 2000 this had been reduced to 20%. A 2004 World Bank report attributed 60% of Chile's 1990's poverty reduction to economic growth, and claimed that government programs aimed at poverty alleviation accounted for the rest.[3]

Hernán Büchi, Minister of Finance under Pinochet between 1985 and 1989, wrote a book detailing the implementation process of the economic reforms during his tenure. Successive governments have continued these policies. In 2002 Chile signed an association agreement with the European Union (comprising free trade and political and cultural agreements), in 2003, an extensive free trade agreement with the United States, and in 2004 with South Korea, expecting a boom in import and export of local produce and becoming a regional trade-hub. Continuing the coalition's free-trade strategy, in August 2006, President Bachelet promulgated a free trade agreement with the People's Republic of China (signed under the previous administration of Ricardo Lagos), the first Chinese free-trade agreement with a Latin American nation; similar deals with Japan and India were promulgated in August 2007. In 2010, Chile was the first nation in South America to win membership in the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development, an organization restricted to the world's richest countries.

Some economists (such as Nobel laureate Amartya Sen) have argued that the experience of Chile in this period indicates a failure of the economic liberalism posited by thinkers such as Friedman, claiming that there was little net economic growth from 1975 to 1982 (during the so-called "pure Monetarist experiment"). After the catastrophic banking crisis of 1982, the state controlled more of the economy than it had under the previous socialist government, and sustained economic growth only came after the later reforms that privatized the economy, while social indicators remained poor.[4] Pinochet's dictatorship made the unpopular economic reorientation possible by repressing opposition to it. This repression included assassinations organized under Operation Condor, mass systematized torture, exile, and the international hunting of dissidents. In all, there were 40,018 victims documented, including 3,065 killed.[5] Rather than a triumph of the free market, the OECD economist Javier Santiso described this reorientation as "combining neo-liberal sutures and interventionist cures".[6]

- ^ "Commanding Heights: Milton Friedman". PBS. Retrieved December 29, 2008.

- ^ Thomas M. Leonard. Encyclopedia Of The Developing World. Routledge. ISBN 1-57958-388-1 p. 322

- ^ "Successes and Failures in Poverty Eradication: Chile" (PDF).

- ^ http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/7c2a7a48-2030-11db-9913-0000779e2340.html#axzz1qL9FWsgp [dead link]

- ^ "Chile recognises 9,800 more victims of Pinochet's rule". BBC News. 18 August 2011.

- ^ Santiso, Javier (2007). Latin America's Political Economy of the Possible: Beyond Good Revolutionaries and Free-Marketeers. MIT Press. ISBN 9780262693592.