Back العبرية الحديثة Arabic Modeans Hebräisch BAR আধুনিক হিব্রু ভাষা Bengali/Bangla عیبری مۆدێرن CKB Ivrit German Σύγχρονα Εβραϊκά Greek Moderna hebrea lingvo Esperanto عبری نوین Persian Hébreu moderne French עברית ישראלית HE

| Modern Hebrew | |

|---|---|

| Hebrew, Israeli Hebrew | |

| עברית חדשה | |

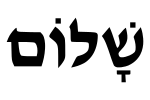

Render of the word "shalom" in Modern Hebrew, including vowel diacritics | |

| Region | Southern Levant |

| Ethnicity | Israeli Jews |

Native speakers | 9 million (2014)[1][2][3] |

Early forms | |

| Hebrew alphabet Hebrew Braille | |

| Signed Hebrew (national form)[4] | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Regulated by | Academy of the Hebrew Language |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | he |

| ISO 639-2 | heb |

| ISO 639-3 | heb |

| Glottolog | hebr1245 |

| |

Modern Hebrew (Hebrew: עִבְרִית חֲדָשָׁה [ʔivˈʁit χadaˈʃa] or [ʕivˈrit ħadaˈʃa]), also called Israeli Hebrew or simply Hebrew, is the standard form of the Hebrew language spoken today. Developed as part of the revival of Hebrew in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it is the official language of the State of Israel and the only Canaanite language still spoken as a native language. The revival of Hebrew predates the creation of the state of Israel, where it is now the national language. Modern Hebrew is often regarded as one of the most successful instances of language revitalization.[7][8]

Hebrew, a Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic language family, was spoken since antiquity and the vernacular of the Jewish people until the 3rd century BCE, when it was supplanted by Western Aramaic, a dialect of the Aramaic language, the local or dominant languages of the regions Jews migrated to, and later Judeo-Arabic, Judaeo-Spanish, Yiddish, and other Jewish languages.[9] Although Hebrew continued to be used for Jewish liturgy, poetry and literature, and written correspondence,[10] it became extinct as a spoken language.

By the late 19th century, Russian-Jewish linguist Eliezer Ben-Yehuda had begun a popular movement to revive Hebrew as a living language, motivated by his desire to preserve Hebrew literature and a distinct Jewish nationality in the context of Zionism.[11][12][13] Soon after, a large number of Yiddish and Judaeo-Spanish speakers were murdered in the Holocaust[14] or fled to Israel, and many speakers of Judeo-Arabic emigrated to Israel in the Jewish exodus from the Muslim world, where many adapted to Modern Hebrew.[15]

Currently, Hebrew is spoken by approximately 9–10 million people, counting native, fluent, and non-fluent speakers.[16][17] Some 6 million of these speak it as their native language, the overwhelming majority of whom are Jews who were born in Israel or immigrated during infancy. The rest is split: 2 million are immigrants to Israel; 1.5 million are Israeli Arabs, whose first language is usually Arabic; and half a million are expatriate Israelis or diaspora Jews.

Under Israeli law, the organization that officially directs the development of Modern Hebrew is the Academy of the Hebrew Language, headquartered at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

- ^ "Hebrew". UCLA Language Materials Project. University of California. Archived from the original on 11 March 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- ^ Dekel 2014

- ^ "Hebrew". Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 14 May 2020. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ^ Meir & Sandler, 2013, A Language in Space: The Story of x Sign Language

- ^ אוכלוסייה, לפי קבוצת אוכלוסייה, דת, גיל ומין, מחוז ונפה [Population, by Population Group, Religion, age and sex, district and sub-district] (PDF) (in Hebrew). Central Bureau of Statistics. 6 September 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 May 2018. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ "The Arab Population in Israel" (PDF). Central Bureau of Statistics. November 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ Grenoble, Leonore A.; Whaley, Lindsay J. (2005). Saving Languages: An Introduction to Language Revitalization. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0521016520.

Hebrew is cited by Paulston et al. (1993:276) as 'the only true example of language revival.'

- ^ Huehnergard, John; Pat-El, Na'ama (2019). The Semitic Languages. Routledge. p. 571. ISBN 9780429655388. Archived from the original on 1 July 2023. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- ^ Language Contact and the Development of Modern Hebrew. BRILL. 16 November 2015. pp. 3, 7. ISBN 978-90-04-31089-6.

- ^ Schwarzwald, Ora (Rodrigue) (2012). "Modern Hebrew". In Weninger, Stefan; Khan, Geoffrey; Streck, Michael P.; Watson, Janet C. E. (eds.). The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook. De Gruyter. p. 534. doi:10.1515/9783110251586.523. ISBN 978-3-11-025158-6.

- ^ Mandel, George (2005). "Ben-Yehuda, Eliezer [Eliezer Yizhak Perelman] (1858–1922)". Encyclopedia of modern Jewish culture. Glenda Abramson ([New ed.] ed.). London. ISBN 0-415-29813-X. OCLC 57470923. Archived from the original on 1 July 2023. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

In 1879 he wrote an article for the Hebrew press advocating Jewish immigration to Palestine. Ben-Yehuda argued that only in a country with a Jewish majority could a living Hebrew literature and a distinct Jewish nationality survive; elsewhere, the pressure to assimilate to the language of the majority would cause Hebrew to die out. Shortly afterwards he reached the conclusion that the active use of Hebrew as a literary language could not be sustained, notwithstanding the hoped-for concentration of Jews in Palestine, unless Hebrew also became the everyday spoken language there.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Fellman, Jack (19 July 2011). The Revival of Classical Tongue : Eliezer Ben Yehuda and the Modern Hebrew Language. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-087910-0. OCLC 1089437441. Archived from the original on 1 July 2023. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ^ Kuzar, Ron (2001), Hebrew and Zionism, Berlin, Boston: DE GRUYTER, doi:10.1515/9783110869491.vii, archived from the original on 1 July 2023, retrieved 10 May 2023

- ^ Solomon Birnbaum, Grammatik der jiddischen Sprache (4., erg. Aufl., Hamburg: Buske, 1984), p. 3.

- ^ Berdichevsky, Norman (21 March 2016). Modern Hebrew: The Past and Future of a Revitalized Language. McFarland. pp. 39, 65, 73, 77, 81, 101. ISBN 978-1-4766-2629-1.

- ^ Klein, Zeev (18 March 2013). "A million and a half Israelis struggle with Hebrew". Israel Hayom. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ^ Nachman Gur; Behadrey Haredim. "Kometz Aleph – Au• How many Hebrew speakers are there in the world?". Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2013.