Back Nasionaal-Sosialistiese Duitse Arbeidersparty Afrikaans Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei ALS الحزب النازي Arabic الحزب النازى ARZ Partíu Nacionalsocialista Obreru Alemán AST Nasional Sosialist Alman Fəhlə Partiyası Azerbaijani NSDAP BAR Нацыянал-сацыялістычная нямецкая рабочая партыя Byelorussian Нацыянал-сацыялістычная нямецкая працоўная партыя BE-X-OLD Националсоциалистическа германска работническа партия Bulgarian

National Socialist German Workers' Party Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei | |

|---|---|

| |

| Abbreviation | NSDAP |

| Chairman | Anton Drexler (24 February 1920 – 29 July 1921)[1] |

| Führer | Adolf Hitler (29 July 1921 – 30 April 1945) |

| Party Minister | Martin Bormann (30 April 1945 – 2 May 1945) |

| Founded | 24 February 1920 |

| Banned | 10 October 1945 |

| Preceded by | German Workers' Party |

| Headquarters | Brown House, Munich, Germany[2] |

| Newspaper | Völkischer Beobachter |

| Student wing | National Socialist German Students' Union |

| Youth wing | Hitler Youth |

| Women's wing | National Socialist Women's League |

| Paramilitary wings | SA, SS, Motor Corps, Flyers Corps |

| Sports body | National Socialist League of the Reich for Physical Exercise |

| Overseas wing | NSDAP/AO |

| Labour wing | NSBO (1928–35), DAF (1933–45)[3] |

| Membership |

|

| Ideology | Nazism |

| Political position | Far-right[5][6] |

| Political alliance | National Socialist Freedom Movement (1924)

|

| Colours |

|

| Slogan | Deutschland erwache! ("Germany, awake!") (unofficial) |

| Anthem | "Horst-Wessel-Lied" |

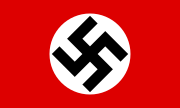

| Party flag | |

| |

| Part of a series on |

| Nazism |

|---|

The Nazi Party,[b] officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (German: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei [c] or NSDAP), was a far-right[10][11][12] political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported the ideology of Nazism. Its precursor, the German Workers' Party (Deutsche Arbeiterpartei; DAP), existed from 1919 to 1920. The Nazi Party emerged from the extremist German nationalist ("Völkisch nationalist"), racist and populist Freikorps paramilitary culture, which fought against communist uprisings in post–World War I Germany.[13] The party was created to draw workers away from communism and into völkisch nationalism.[14] Initially, Nazi political strategy focused on anti–big business, anti-bourgeois, and anti-capitalist rhetoric; it was later downplayed to gain the support of business leaders. By the 1930s, the party's main focus shifted to antisemitic and anti-Marxist themes.[15] The party had little popular support until the Great Depression, when worsening living standards and widespread unemployment drove Germans into political extremism.[12]

Central to Nazism were themes of racial segregation expressed in the idea of a "people's community" (Volksgemeinschaft).[16] The party aimed to unite "racially desirable" Germans as national comrades while excluding those deemed to be either political dissidents, physically or intellectually inferior, or of a foreign race (Fremdvölkische).[17] The Nazis sought to strengthen the Germanic people, the "Aryan master race", through racial purity and eugenics, broad social welfare programs, and a collective subordination of individual rights, which could be sacrificed for the good of the state on behalf of the people. To protect the supposed purity and strength of the Aryan race, the Nazis sought to disenfranchise, segregate, and eventually exterminate Jews, Romani, Slavs, the physically and mentally disabled, homosexuals, Jehovah's Witnesses, and political opponents.[18] The persecution reached its climax when the party-controlled German state set in motion the Final Solution – an industrial system of genocide that carried out mass murders of around 6 million Jews and millions of other targeted victims in what has become known as the Holocaust.[19]

Adolf Hitler, the party's leader since 1921, was appointed Chancellor of Germany by President Paul von Hindenburg on 30 January 1933, and quickly seized power afterwards. Hitler established a totalitarian regime known as the Third Reich and became dictator with absolute power.[20][21][22][23]

Following the military defeat of Germany in World War II, the party was declared illegal.[24] The Allies attempted to purge German society of Nazi elements in a process known as denazification. Several top leaders were tried and found guilty of crimes against humanity in the Nuremberg trials, and executed. The use of symbols associated with the party is still outlawed in many European countries, including Germany and Austria.

- ^ Kershaw 1998, pp. 164–65.

- ^ Steves 2010, p. 28.

- ^ T. W. Mason, Social Policy in the Third Reich: The Working Class and the "National Community", 1918–1939, Oxford: UK, Berg Publishers, 1993, p. 77.

- ^ McNab 2011, pp. 22, 23.

- ^ Davidson 1997, p. 241.

- ^ Orlow 2010, p. 29.

- ^ Pfleiderer, Doris (2007). "Volksbegehren und Volksentscheid gegen den Youngplan, in: Archivnachrichten 35 / 2007" [Initiative and Referendum against the Young Plan, in: Archived News 35 / 2007] (PDF). Landesarchiv Baden-Württemberg (in German). p. 43. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 December 2022. Retrieved 26 November 2022.

- ^ Jones, Larry E. (Oct., 2006). "Nationalists, Nazis, and the Assault against Weimar: Revisiting the Harzburg Rally of October 1931" Archived 26 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine. 'German Studies Review. Vol. 29, No. 3. pp. 483–94. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- ^ Jones 2003.

- ^ Fritzsche 1998, pp. 143, 185, 193, 204–05, 210.

- ^ Eatwell, Roger (1997). Fascism : a history. New York: Penguin Books. pp. xvii–xxiv, 21, 26–31, 114–40, 352. ISBN 0-14-025700-4. OCLC 37930848.

- ^ a b "The Nazi Party". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Archived from the original on 31 January 2023. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- ^ Grant 2004, pp. 30–34, 44.

- ^ Mitchell 2008, p. 47.

- ^ McDonough 2003, p. 64.

- ^ Majer 2013, p. 39.

- ^ Wildt 2012, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Gigliotti & Lang 2005, p. 14.

- ^ Evans 2008, p. 318.

- ^ Arendt 1951, p. 306.

- ^ Curtis 1979, p. 36.

- ^ Burch 1964, p. 58.

- ^ Maier 2004, p. 32.

- ^ Elzer 2003, p. 602.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).