| Nuclear weapons |

|---|

|

| Background |

| Nuclear-armed states |

|

Nuclear ethics is a cross-disciplinary field of academic and policy-relevant study in which the problems associated with nuclear warfare, nuclear deterrence, nuclear arms control, nuclear disarmament, or nuclear energy are examined through one or more ethical or moral theories or frameworks.[1][2][3]

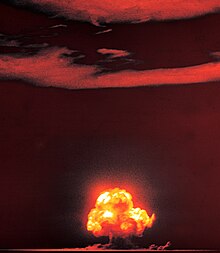

Nuclear ethics assumes that the very real possibilities of human extinction, mass human destruction, or mass environmental damage which could result from nuclear warfare are deep ethical or moral problems. Specifically, it assumes that the outcomes of human extinction, mass human destruction, or environmental damage count as moral evils. Another area of inquiry concerns future generations and the burden that nuclear waste and pollution imposes on them. Some scholars have concluded that it is therefore morally wrong to act in ways that produce these outcomes, which means it is morally wrong to engage in nuclear warfare.[4]

Nuclear ethics is interested in examining policies of nuclear deterrence, nuclear arms control and disarmament, and nuclear energy insofar as they are linked to the cause or prevention of nuclear warfare. Ethical justifications of nuclear deterrence, for example, emphasize its role in preventing great power nuclear war since the end of World War II.[5] Indeed, some scholars claim that nuclear deterrence seems to be the morally rational response to a nuclear-armed world.[6] Moral condemnation of nuclear deterrence, in contrast, emphasizes the seemingly inevitable violations of human and democratic rights which arise.[7] In contemporary security studies, the problems of nuclear warfare, deterrence, proliferation, and so forth are often understood strictly in political, strategic, or military terms.[8] In the study of international organizations and law, however, these problems are also understood in legal terms.[9]

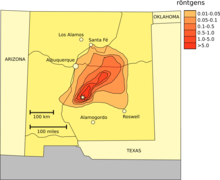

Nuclear technology has seen the formation of an anti-nuclear movement since its early development, and grew with the increased impact of it, particularly nuclear weapons testing,[10] caused the deaths of up to 2.4 million people until 2020.[11]

- ^ Doyle, II, Thomas E. (2010). "Reviving Nuclear Ethics: A Renewed Research Agenda for the Twenty-first Century". Ethics and International Affairs. 24 (3): 287–308. doi:10.1111/j.1747-7093.2010.00268.x. S2CID 144502441.

- ^ Nye, Joseph Jr. (1986). Nuclear Ethics. New York: The Free Press. ISBN 978-0-02-923091-6.

- ^ Sohail H. Hashmi and Steven P. Lee, ed. (2004). Ethics and Weapons of Mass Destruction: Religious and Secular Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-54526-6.

- ^ Doyle, II, Thomas E. (2010). "Kantian nonideal theory and nuclear proliferation". International Theory. 2 (1): 87–112. doi:10.1017/s1752971909990248. S2CID 202244223.

- ^ Nye, Joseph S Jr. (1986). "5". Nuclear Ethics. New York: The Free Press. pp. 59–80.

- ^ Kavka, Greg S. (1978). "Some Paradoxes of Deterrence". Journal of Philosophy. 75 (6): 285–302. doi:10.2307/2025707. JSTOR 2025707.

- ^ Shue, Henry (2004). "7". In Sohail H. Hashmi and Steven P. Lee (ed.). Ethics and Weapons of Mass Destruction: Religious and Secular Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 139–162.

- ^ Buzan, Barry; Hansen, Lene (2009). "4". The Evolution of International Security Studies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-69422-3.

- ^ Szasz, Paul C. (2004). "2". In Sohail H. Hashmi and Steven P. Lee (ed.). Ethics and Weapons of Mass Destruction: Religious and Secular Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 43–72.

- ^ Fee, Elizabeth; Brown, Theodore M. (2004). "Dispelling the Specter of Nuclear Holocaust". American Journal of Public Health. 94 (1): 36–36. doi:10.2105/AJPH.94.1.36. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 1449821. PMID 14713693.

- ^ Adams, Lilly (26 May 2020). "Resuming Nuclear Testing a Slap in the Face to Survivors". The Equation. Retrieved 16 July 2024.